MEMORIES – IRENE MARY CORFIELD (1919-2013)

My mother, Irene Mary Corfield (née Hill)1, was a remarkable woman who lived a private life but seemed, through the quiet force of her personality, to represent a veritable strand of British public identity. She was born on 18 March 1919, the second child and only daughter of a York solicitor with a strong Methodist faith. As a child, Irene was reserved and shy. Her parents were kindly but relatively aloof (they were much more fun as grand-parents). The whole family went to Methodist chapel three times a day on Sundays; the sermon was discussed seriously; and Sundays were strictly observed. Her parents were teetotal and suspicious of worldly temptations. Their large, rambling house, in a village just outside York, was an idyllic place for Irene’s children to visit, later on, for summer holidays. Yet she was often lonely there and sought companionship with the housemaid. When the teenage Irene was sent as a weekly border to York’s Mount School for Girls, she revelled in its relaxed and companionable atmosphere – and imbibed a strong dose of liberal Quaker egalitarianism.

Her background was thus steeped in Nonconformist values, matched with a permanent element of ‘plain Yorkshire’. To the end of her days, her personal mantra was ‘no fuss’ – and she meant it.

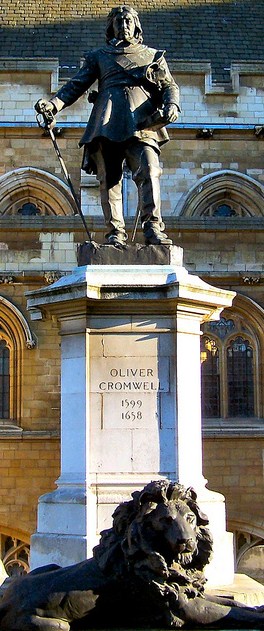

When young, she always felt over-shadowed by her brilliant older brother and only sibling: Christopher Hill (1912-2003), who became a celebrated historian and later Master of Balliol.2 He was seven years older than Irene and seemed, to her at least, to be the family favourite. They were not particularly close as youngsters. Nonetheless, they not only looked alike but had strong affinities in character and world-views. Christopher Hill’s break with Methodism greatly shocked and distressed his parents. There was an unprecedented Hill family drama when Christopher took Irene to see a show at York’s Theatre Royal. Their father was so upset that he took to his bed in silent horror for two days. Nonetheless, the taboo was broken.

Christopher Hill had thus paved the way for Irene to announce quietly, at the age of 21, that she no longer intended to go to chapel. Her parents accepted the news with sad resignation. And they had no hesitation in encouraging their talented daughter to follow in Christopher’s footsteps by studying at Oxford.

Irene went up to St Anne’s College in 1938, studying French and German. She had strong literary gifts, and remained a fluent reader in both languages all her life. University life brought further liberation. She loved her studies; made long-lasting friendships; added an optimistic strand of socialism to her secularised Quaker values; and joined Oxford’s Labour Club. Halfway through her first year, she met Alan Corfield (1919-2011), a History undergraduate at Keble College, who was always known as Tony. She had noticed him noticing her, as she told her children later. Without a word, they manoeuvred during a Paul Jones ‘mixer’ dance at a Labour Club social to become partners. And so they remained.

The joint simplicity and commitment of Tony and Irene was heart-warming. As was their jollity and droll humour. They began to live together and then, after Tony had volunteered for the army in 1940, decided to get married. Wives were allowed conjugal visits to soldiers, while partners were not. Of the two personalities, Tony Corfield was the more outgoing, teasing his shy wife as ‘Bumptious’. Their children, struggling with the difficult word, renamed her as Bumper, which became her name within the family. But, while she remained quiet in company, people quickly recognised both her rock-like steadfastness and her intelligent sympathy with others. She organised Tony as well as their six children. They shared a modest lifestyle of ‘plain living and high thinking’, to borrow an apt expression from Wordsworth. Incidentally, Irene could recite many of his poems by heart and still did so in her last illness, at the age of 94.

The joint simplicity and commitment of Tony and Irene was heart-warming. As was their jollity and droll humour. They began to live together and then, after Tony had volunteered for the army in 1940, decided to get married. Wives were allowed conjugal visits to soldiers, while partners were not. Of the two personalities, Tony Corfield was the more outgoing, teasing his shy wife as ‘Bumptious’. Their children, struggling with the difficult word, renamed her as Bumper, which became her name within the family. But, while she remained quiet in company, people quickly recognised both her rock-like steadfastness and her intelligent sympathy with others. She organised Tony as well as their six children. They shared a modest lifestyle of ‘plain living and high thinking’, to borrow an apt expression from Wordsworth. Incidentally, Irene could recite many of his poems by heart and still did so in her last illness, at the age of 94.

In another era, she would have sought her own career. She said so herself but, in the 1940s and 1950s, it was much more common for mothers to stay at home. Irene did not fuss about making that choice and, while she later empathised with her daughters’ careers, she did not particularly envy them.

During the war, her languages were put to use when she was employed in the censor’s office (Ministry of Information) at Whitehall, monitoring letters from Germany. But, after that, she did casual jobs, to fit around her domestic timetable, whilst providing tireless backup for Tony throughout his career in trade unionism and adult education.3 At Oxford in the 1940s, Irene marked essays for Ruskin College. In Sidcup, where the family moved in 1950, she taught long-stay sick children in hospital; and lectured for the Workers’ Educational Association on social issues, like feminism and drugs. Later, when Tony’s job took him to Birmingham’s Fircroft College from 1971-6, she taught remedial English; and then acted as Tony’s assistant at the Birmingham Environmental Health & Safety Association. In her own eighties, she became firstly the secretary and then the active chair of the Residents’ Association at Dulwich Mead, the warden-assisted housing complex, where she and Tony lived in serene retirement after 2000.

Irene was also for thirty-seven years an active JP in both Sidcup and Birmingham. As a magistrate, she was initially told that ladies on the bench must wear a hat. But, after a tussle, she presided hatless, with calm authority.

In her chosen metier as a parent, she excelled. She was warm and loving, without ever shedding good discipline. It was rare to see her angry or even disconcerted. While she was always busy, she was never fussed. She stood by her children like a strong but gentle lion. If we quarrelled amongst ourselves, she became unhappy, with the result that we rarely did. In all, she was the quintessence of loving motherhood. I remember once as a ten-year-old fainting while walking up a steep hill on a hot summer day and recovering in her arms, to hear her saying tenderly: ‘I’ve got you, I’ve got you’. The flood of reassurance remains with me today.

Irene/Bumper’s success as a parent was particularly creditable since she broke the pattern of what she considered to be her inadequate upbringing. I have heard many people declare their intentions of avoiding their own parents’ mistakes in child-rearing – and then seen them fail. Needless to say, Irene/Bumper never gushed. But she broke from the Hill family pattern, among the older generation, of rearing children with good principles but lacking physical warmth. She cuddled her own children and effortlessly conveyed love.

How to assess the wider impact of such a private person? In many ways Irene fell into the category analysed by George Eliot at the end of Middlemarch (1871/2).4 Hers was one of those ‘hidden’ lives which have significance beyond their immediate circles. Irene impressed those she met with her mix of intelligence, wisdom, humour, and steadfastness. In a wider sense, she represented a form of secularised Dissent as it merged into a steady support for the Labour Party, the United Nations Association, and the Co-operative movement. She was a truly good woman, who believed that there was good in everyone.

Bolstered by her strong beliefs and a supremely loving marriage, she lived a long and deeply fulfilled life, surrounded by books, flowers, the Guardian cross-word, Labour Party leaflets, and children. Minor irritants, such as her dislike of cooking, were taken in her stride. And her major sorrows were met with her characteristic stoicism in grief: the death of her oldest son Adrian from lymphoma at the age of 44 in 1990; and the slow physical and mental decline of Tony Corfield, in the very last years before his death in 2011.

Could such a paragon be obstinate? Yes, Irene/Bumper could. When she set her Hill jaw and said ‘Now then’, it was a sign that she had dug in her heels. Yet it was no doubt to counterbalance the risk of undue obstinacy that she had married the more unpredictable, though equally dedicated, Tony Corfield.

Lastly, it’s worth recording Irene’s forte as a letter-writer. She wrote regularly to friends and absent family. They were letters to be savoured, with an amusing text crammed onto every page and often ending with a whimsical PS from Tony Corfield. On serious occasions, she wrote powerfully from the heart. A shy, gentle, and much younger friend named Liz had a failed marriage and, after a very bitter divorce, was (most unusually) not awarded custody of her three young daughters or even granted visiting rights. The distraught Liz received a consoling letter from Irene. It reassured her that Liz’s daughters would come and find her as soon as they were old enough to choose for themselves. Years passed. We gradually lost touch. Then we heard that Liz was tragically killed in a cycling accident. In her handbag was Irene’s letter.

Lastly, it’s worth recording Irene’s forte as a letter-writer. She wrote regularly to friends and absent family. They were letters to be savoured, with an amusing text crammed onto every page and often ending with a whimsical PS from Tony Corfield. On serious occasions, she wrote powerfully from the heart. A shy, gentle, and much younger friend named Liz had a failed marriage and, after a very bitter divorce, was (most unusually) not awarded custody of her three young daughters or even granted visiting rights. The distraught Liz received a consoling letter from Irene. It reassured her that Liz’s daughters would come and find her as soon as they were old enough to choose for themselves. Years passed. We gradually lost touch. Then we heard that Liz was tragically killed in a cycling accident. In her handbag was Irene’s letter.

Irene Mary Corfield (née Hill) was born on 18 March 1919, the only daughter of Edward Harold Hill and Janet Augusta Hill (née Dickinson); and died on 6 April 2013. She married Alan ‘Tony’ Corfield on 30 December 1941. They had six children: Penelope Jane (b. 1944); Adrian (1946-90); Julian (b. 1948); Alison (b. 1950); Christopher (b. 1956); Rebecca (b. 1959). They have four grand-children: Melissa (b. 1973); Sherena (b. 1990); Victoria (b. 1997); Jeremy (b. 1999). And one great-grand-daughter: Scarlett Claire (b. 2012).

1 A short version of this account is available on The Guardian website, 13 May 2013: read here.

2 See Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, on-line; plus obituary in The Guardian, 26 Feb. 2003; further appreciation by P.J. Corfield, The Guardian, 6 March 2003; and P.J. Corfield, ‘“We are All One in the Eyes of the Lord”: Christopher Hill and the Historical Meanings of Radical Religion’, History Workshop Journal, 58 (2004), pp. 110-27 – also reprinted in PJC website www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk: What is History? pdf/5.

3 P.J. Corfield, Short obituary of Tony Corfield in The Guardian, 2 Sept. 2011; and longer account of Tony Corfield and the T&G, on website of UnitetheUnion, Sept. 2011 – both reprinted in PJC website www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk: see Career pdf/18.

4 G. Eliot, Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life (1871/2; in Penguin edn., 1969), p. 896.

To read other notices, please click here.