OBITUARY: LILIAN (LILY) ROSE HARRISON, NÉE PARKER, MBE (1924-2015)

from Battersea Labour Party

Annual Report (2015), pp. 23-4

Lily Harrison had a strong, feisty, ‘giving’ personality, with an intense civic commitment to the Shaftesbury Estate community in particular and to Battersea in general. In another generation, when opportunities for working-class women were greater, she would have taken a front-seat role. But she did more as an active grass-root, throughout a long and non-stop life, than many front-benchers. Her award of an MBE in 2008 was a justified honour.

For Battersea Labour Party, Lily was not only the longest lived of a post-war generation of committed working-class activists who ran Labour in its unchallenged prime within the area – but she was also a personal link between three generations of truly remarkable women in Battersea left-wing politics. Lily worked closely with Caroline Ganley (1879-1966), who was Labour MP for Battersea South (1945-51) and a long-standing Battersea Councillor (1919-25, 1953-65). And in turn Caroline Ganley had worked closely with Charlotte Despard (1844-1939), the pioneering suffragette and left-winger, who lived in working-class Nine Elms and stood (alas, unsuccessfully) for Labour in Battersea in the 1919 general election. It was Charlotte Despard who purchased 177 Lavender Hill as BLP’s headquarters; and it was Lily Harrison who for many years ran 177 as its guardian figure.

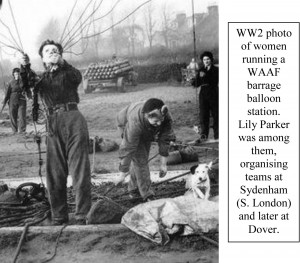

Lily was born in Canning Town, East London, into a family of working-class Tories. After a sickly childhood, she grew into a wiry and indefatigable adult. She left school at 14, working as a sewing machinist. In 1941 she joined the WAAF and had a ‘good’ war, proud of her contribution to London’s home defence. At one stage, she was in charge of a team of women operating the huge barrage balloons on Sydenham Hill in south London, which were used to disrupt the flight of enemy bombers as they tried to blitz Battersea’s industries and rail networks. It was a challenging task, Lily told me, not just technically but also because she had to manage a team of ‘flighty’ young women who were not used to physical labour and were all too keen on enjoying wartime London’s night-life. Later, she was in charge of a similar team operating barrage balloons on the cliffs of Dover at the time of D-Day.

When stationed on war duties in Cambridge in 1944, Lily met her husband Herbert (Bert) Harrison, nicknamed ‘Ginger’ for his auburn locks. Married in 1947, they were devoted to one another and to their growing family: two surviving sons, Edward and Derek, and a daughter Joan, who had Down’s Syndrome and died from pneumonia at the age of two. At that time, many parents used to put Down’s children into institutional care. But, as Derek Harrison recalled: ‘Not Lily! She dressed Joan in a red coat and displayed her to the world, lovingly declaring “That’s my daughter”.’ The little coat was kept as a treasured family memento, and was buried with Lily.

Bert Harrison came from a politically committed Labour family. His own father, another Herbert Harrison, had been a Labour Councillor and Mayor of Battersea (1953); and Bert followed in his footsteps, representing Shaftesbury Ward on Battersea Borough Council. For Lily, joining the Harrison clan meant that her leftish sympathies were suddenly jolted into non-stop activism. ‘It was a steep learning curve’, she admitted, but one that she thoroughly enjoyed.

When interviewed for the making of BLP’s DVD Red Battersea (2008), Lily gave me the following account of her role in Battersea Labour: ‘After Bert was elected for Shaftesbury ward, I attended every Council meeting for fifteen years. I became a dedicated Party nut! I lost half a stone in weight during my first General Election campaign, in 1964 – but it was worth it because we got Ernie Perry in [as MP for Battersea South] with a big majority. Later, I ran the BLP Afternoon Section for the older ladies: we had jumble sales, garden parties, raffles, knit-ins, and dinner parties, the annual Bazaar. You name it, I’ve organised it. It’s been my life.’

Lily and Bert, who lived on the Shaftesbury Estate, were also part of the strong community life of the Estate; as well as busy in many other local projects. After Bert’s death in 1990, Lily continued her civic involvement, being active on: Battersea Arts Centre Board (founder member from 1971 and later Trustee); Battersea United Charities (Trustee from 1960 and chair 1990-2006); Bolingbroke Hospital Friends; St George’s Hospital Friends; Tooting & Balham Carnival Committee (member from 1971; secretary 1984-94); and SHARE Community (Self-Help Association for Rehabilitation & Employment), of which she became Life Vice President. She wound down only when halted by illness, late in life.

As that account indicates, Lily had the gift of working well with others. She always did what she’d promised to do, with efficiency and good humour. She got on well with most people, and faced the twists and turns of politics with a certain stoicism. In organisational terms, her greatest regret was that Bert did not become Mayor of Battersea, as his father had done before him, or Mayor of Wandsworth, the larger authority that swallowed Battersea Borough Council in 1965. And there’s no doubt that Lily would have made a great Mayoress.

Yet her tireless activism showed that civic individuals don’t need an official position to get involved. By the end of her long life, Lily had friends across the political spectrum. That’s because – unofficially – she was for many years the equivalent of an uncrowned Lady Mayor of Battersea. But she was no mere ceremonial figure. Lily was nothing if not hands-on. It’s how she lived her life.

To download a pdf of this obituary please click here