MONTHLY BLOG 141, A YEAR OF GEORGIAN CELEBRATIONS – 9: Annual Commemorations of the Battle of Trafalgar & the Death of Nelson

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2022)

|

Image from Broadside Ballad |

Trafalgar! Most Britons know the name. They don’t all know the date of the famous naval battle on 21 October 1805. Or its location, offshore from Cape Trafalgar, on the Atlantic coast of southern Spain – close to the nautical approach into the Straits of Gibraltar.

Above all, however, most Britons do know that the British fleet won a famous victory.1 Admiral Nelson made an audacious naval charge that broke up a huge combined flotilla of French and Spanish galleons. By dividing his enemies, he circumvented their numerical supremacy, in terms of both ships and guns. The French Admiral was forced to sail onwards before he could cumbrously turn his galleons around to rejoin the battle.

But by the time he returned, the damage was done. Britain’s navy had triumphed, taking or sinking 22 enemy ships, for the loss of none of its own. It had also killed or wounded almost 7,000 men, and taken captive a further 7-8,000. In sum, it was a decisive confirmation of Britain’s increasingly apparent but now confirmed naval predominance.

Britain’s casualties, meanwhile, were comparatively light. 458 sailors were killed; and 1,200 wounded. However, the headline news that accompanied the story of a great victory was the death of Admiral Nelson in the heat of battle. His fame, already growing, became legendary.2

This heroic figure, who had already lost an eye and an arm in earlier battles, again put his life on the line, fighting alongside his sailors, on the aptly named British flagship HMS Victory.

In the short term, the battle of Trafalgar had little immediate impact upon the warfare between Britain and its various continental allies against Napoleonic France. The main theatres of engagement were on land. Indeed, on 2 December 1805, Napoleon won the battle of Austerlitz decisively, routing the combined armies of the Austrian, Prussian and Russian Emperors. And he went on to further successes.

Nonetheless, within Britain, the engagement at Trafalgar gave a major boost to morale. Moreover, the British Navy had henceforth established its command of the high seas. That had long-term consequences.

Meanwhile, Nelson himself became a revered symbol of indomitable resistance. His heroism was immediately commemorated in songs and ballads.3 These were widely circulated, as the informal equivalent to later popular radio. Tellingly, one later ballad about The Battle of Trafalgar (c.1850) invented the following final words from the dying Admiral:

“Fight on, fight on like Britons”, bold Nelson he did say;

“Fight on my gallant heroes, you are sure to gain the day.”

Dogged confidence in eventual victory is a great psychological asset amongst a people engaged in prolonged warfare. Countless monuments were erected to Nelson as a fallen hero. But the most conspicuous were ten towering columns in his honour. They stand like vigilant guardians. The best known of these monuments is Nelson’s Column in London’s central Trafalgar Square. Yet that striking edifice (built 1840-3) was the last to be constructed.

Eight Nelson columns were in fact constructed during the Napoleonic Wars themselves. Symbolically, they indicated resolute defiance. They were erected in diverse venues, following initiatives from loyal citizens, or by country landowners, and, in one case, by Nelson’s fellow naval officers. The cost was borne by the navy itself, including contributions docked from the pay of ordinary seamen who had served at Trafalgar.

These towering monuments include. in order of construction: the Nelson Monument on Glasgow Green (1806); the Nelson Obelisk in Swarland Hall Park, Northumbria (1807); Nelson’s Column on Edinburgh’s Calton Hill (begun 1807); the Nelson Monument on Portsdown Hill, near Portsmouth (1808), built on the initiative of naval officers; Nelson’s Column in the heart of Canada’s Montreal (1808-9); Nelson’s Pillar in central Dublin (1809; demolished after bombing in 1966);4 Nelson’s Column on Castle Green in Hereford (1809); and Nelson’s Monument on Birchen Edge in Derbyshire (1810).

Added to those, not long after the end of the Napoleonic wars, a dramatic memorial was constructed by the seaside at Great Yarmouth. It is dedicated to Nelson as the Norfolk-born saviour of the nation. But it is known as the Britannia Monument, being topped by a figure of that majestic lady. She holds in one hand a trident and in the other, an olive branch. Nelson and the British nation triumph together, making peace but not forgetting the nautical underpinning of British power.

Needless to say, it was entirely possible for individuals to pass such monuments without knowing to whom they were dedicated. But, collectively, they became talking-points. The number of heroic figures in Britain who are honoured with columns and obelisks is only small – and none have anything like Nelson’s tally.

Given this heritage, it is no surprise, then, that the anniversary of Trafalgar has never been forgotten. It is treated by the Royal Navy as both a celebration and a day of remembrance. Aboard HMS Victory, now lovingly tended in Portsmouth’s Historic Dockyard, flags are flown to signal Nelson’s famous message on the day of battle: ‘England Expects Every Man to do his Duty’.5 Sea cadets parade in London’s Trafalgar Square. Naval dinners are held at which a toast is given to ‘The Immortal Memory’. And festivities are held at other places with a Nelson-link, such as the settlements of Nelson in New Zealand, and Trafalgar, in the Australian state of Victoria.

What would the hero himself have said about all this fuss? He was a man of few (recorded) words. He would no doubt thank everyone crisply but then urge them to get on with the tasks in hand. Nelson doggedly went his own way.

During his lifetime, he managed to face down the scandal attached to his love affair with the married Lady Emma Hamilton,6 And, recently, his admirers are firmly defending him against accusations of racism and an unwillingness to condemn the increasingly controversial slave trade that he encountered when on active service in the West Indies.7

Nelson was, however, an obsessively single-minded man. He did not seek money or social advancement or political power. He wanted to deploy his unorthodox nautical skills to serve his country. His dream was of naval glory. And, yes: he and his sailors, drawn from many different ethnic backgrounds,8 became legends.

ENDNOTES:

1 Among a huge literature, see N. Best, Trafalgar: The Untold Story of the Greatest Sea Battle in History (2006); P. Warwick, Voices from the Battle of Trafalgar (Newton Abbot, 2005); S. Willis, The Battle of Trafalgar (2019). See also the ‘Panorama of the Battle of Trafalgar’, painted by W.L. Wyllie in 1930, on display at Portsmouth Dockyard Museum. And, for wider context, consult N.A.M. Rodger, The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy (1986; 2009).

2 C. Hibbert, Nelson: A Personal History (1994; 2002); R.J.B. Knight, The Pursuit of Victory: The Life and Achievement of Horatio Nelson (2006); J. Sugden, Nelson: The Sword of Albion (2012); Q. Colville and J. Davey, Nelson, Navy and Nation: The Royal Navy and the British People, 1688-1815 (2013).

3 See collections such as J. Fairburn, Naval Songster: Or Jack Tar’s Chest of Conviviality for 1806 – Being an Excellent Cargo of Celebrated, Popular and Choice Sea-Songs Intended to Commemorate the Last Glorious Victory, Death and Memory … of Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson [1806]; and Anon., Nelson’s Garland of New Songs, containing (1) The Battle of Trafalgar … (2) Nelson’s Victories … [Newcastle, 1810?].

4 The granite Pillar was severely damaged by republican bombing in 1966, and then demolished – although the individual bombers were never identified by police. Its presence in Dublin had long been controversial, with growing nationalist resentment at such a prominent honouring of an Englishman with no Irish connections.

5 ‘England Expects …’ (NB. Not ‘Britain Expects’) became a widely quoted phrase, which has been used in equivalent (or similar) phrasing by other navies, including the French, the American and the Japanese: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/England_expects.

6 B.M. Gough, That Hamilton Woman: Emma and Nelson (Barnsley, 2016).

7 See e.g. the Nelson Society’s ‘Position Statement on Nelson and the Slave Trade’ (2021), posted in https://nelson-society.com/nelson-and-the-slave-trade-a-position-statement-by-the-nelson-society (accessed 19 August 2022).

8 R. Costello, Black Salt: Seafarers of African Descent on British Ships (Liverpool, 2012); J.D. Ellis, ‘Black Sailors in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, 1793-1815’ (Oct. 2020), posted in https://www.historycalroots.com/black-sailors-in-the-royal-navy-during-the-napoleonic-wars (accessed 19 August 2022). In a Victorian acknowledgement of that history, the bronze relief of sailors at Trafalgar, installed at the foot of Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square (1849), depicts a sailor of African heritage.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 141 please click here

Good-looking, debonair, raffish, sexy, attractive to both men and women, a breezy poet, a dog-lover, a radical in his politics, supporting working-class interests at home and Greek independence overseas, and a man with a title – George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), seemed almost too amazing to be true.1 But add into the mix the further pertinent facts that he was chronically impoverished; that he had a deformed foot, which gave him pain and forced him to walk with a limp; that he took to travelling restlessly overseas; that his marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke was unhappy; that many of his affairs were also tormented and short-lived; that there were accusations of incest with his half-sister and marital violence; that, as a result, Byron was considered deeply controversial by respectable society; … and his story was not straightforward.

Good-looking, debonair, raffish, sexy, attractive to both men and women, a breezy poet, a dog-lover, a radical in his politics, supporting working-class interests at home and Greek independence overseas, and a man with a title – George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), seemed almost too amazing to be true.1 But add into the mix the further pertinent facts that he was chronically impoverished; that he had a deformed foot, which gave him pain and forced him to walk with a limp; that he took to travelling restlessly overseas; that his marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke was unhappy; that many of his affairs were also tormented and short-lived; that there were accusations of incest with his half-sister and marital violence; that, as a result, Byron was considered deeply controversial by respectable society; … and his story was not straightforward.

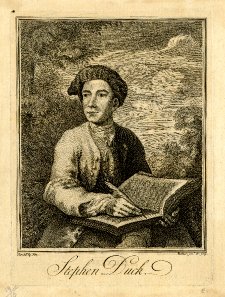

This BLOG resumes the theme of links between the Georgian era and the present.1 To do that, it takes one remarkable case-history, that of the Wiltshire poet, Stephen Duck (c.1705-56). [Yes, that was his real name] He was the son of an impoverished agricultural labourer. It’s likely that both his parents were illiterate. Yet Stephen Duck not only grew to gain poetic fame during his relatively short life but has been honoured ever since by an annual Duck Feast, held in his home village of Charlton, near Pewsey in Wiltshire.2

This BLOG resumes the theme of links between the Georgian era and the present.1 To do that, it takes one remarkable case-history, that of the Wiltshire poet, Stephen Duck (c.1705-56). [Yes, that was his real name] He was the son of an impoverished agricultural labourer. It’s likely that both his parents were illiterate. Yet Stephen Duck not only grew to gain poetic fame during his relatively short life but has been honoured ever since by an annual Duck Feast, held in his home village of Charlton, near Pewsey in Wiltshire.2