MONTHLY BLOG 116, THE LONG EIGHTEENTH CENTURY’S MOST AMAZING LADY RECLUSE

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2020)

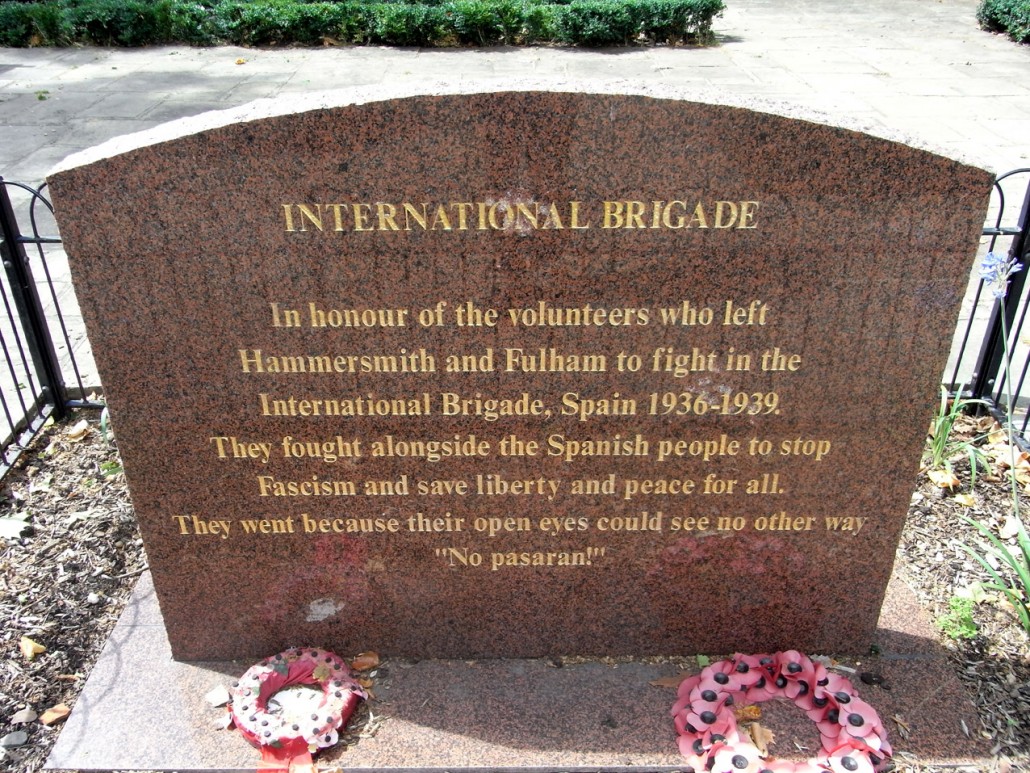

| Image of Lady Hester Stanhope (1776-1839) Garbed as an Oriental Magus |

More than matching the fame of the most notable male recluses of eighteenth-century Britain was the renown of the amazing Lady Hester Stanhope.1 She not only cut herself off from her aristocratic family background to live remotely but did so, at first in grand style and then as a recluse, in the Lebanon.

Her story indicates that there were some remarkable options open to independent-minded women, with independent fortunes but no family attachments. In fact, there was quite a substantial amount of female solitude in the eighteenth century.2 The caricature view, which asserts that every woman was under the domestic tutelage of either a husband or a father was just that – a caricature.

There were plenty of female-headed households listed in contemporary urban enumerations; and a number of these were formed by widows living alone. Many lived in the growing spas and resorts, where low-cost lodgings were plentiful. Some would have other family members living with them; but the poorest were completely alone. In Jane Austen’s Persuasion (1817), the protagonist Anne Elliott meets in Bath an old school-friend, the widowed Mrs Smith. She is impecunious and disabled. Her lodgings consist of two small rooms; and she is ‘unable even to afford herself the comfort of a servant’. Nonetheless, solitary living was not the same as being a recluse. Local gossip networks helped to counter isolation, as Jane Austen well understood. Hence, although socially remote from Bath’s smart visitors, Mrs Smith gets all the up-to-date news ‘through the short cut of a laundress and a waiter’.3 As a result, Anne Elliott is surprised to discover how much information about herself and her family is already known to her old friend.

Lady Hester Stanhope was utterly different. Lively, charming, and wealthy, she was the daughter of the 3rd Earl Stanhope and, in her late twenties (1803-6) acted as political hostess for her uncle Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. Her social elevation and experience of life at the heart of government gave her immense self-confidence. But Pitt’s death in 1806 left her looking for a role.

In retrospect, Stanhope’s subsequent adventures indicate something of the social plight – or, put more positively, the challenges – facing talented and spirited upper class women, who did not wish (or manage) to marry or to go into business. There were plenty of female commercial entrepreneurs, usually of ‘middling’ social origins.4 And there was a positive ‘femocracy’ of high-born women who pulled the political strings behind the scenes.5 But these were generally married ladies, hosting salons and gatherings for their particular party affiliation, under the ‘shelter’ of their husband’s rank and wealth. The options were much more limited for a single aristocratic female, albeit one with a modest state pension granted after the death of Pitt (at his request). In 1810 Stanhope began to travel extensively in the Middle East; and she never returned to Britain. Initially, she had a sizeable entourage with her; and she attracted the attention of crowds as she toured. By the end of her life, however, she was running out of money and had become a complete recluse.

During her long self-exile, she did a number of remarkable things. Firstly, she adopted her own version of male oriental dress. She sported a velvet robe, embroidered trousers, soft slippers, a swathed turban. and no veil. So attired, she caused a sensation on her travels. In 1813, crowds gathered to see the ‘Queen of the Desert’ as she rode triumphantly on horseback into the remote and beautiful city of Palmyra, having crossed the territory of potentially hostile Bedouins. That moment was, for her, one of intense joy. Her garb and demeanour signalled that she had cut herself off from her previous life; and, even more pointedly, that she rejected any submissive female role, whether in the occident or orient. She was visibly her own person. Indeed, she was a grand personage, meeting local power brokers and Ottoman officials as a potentate in her own right.

A second notable initiative happened in 1815. Stanhope at the age of 39 broke new ground in terms of female self-employment – literally, when she tried some pioneering archaeology.6 She won permission from the Turkish authorities to excavate the ancient port of Ashkelon, north of Gaza. There were disputes, both then and later, about the outcomes of this search for fabled treasure. But Stanhope’s method of basing dirt-archaeology upon documentary evidence from medieval manuscripts showed that she was not attempting a random smash-and-grab raid. But, either way, it was not an adventure that she ever repeated.

Instead, it was a moment of religious revelation which constituted Stanhope’s third claim to fame – and which governed her behaviour for the rest of her life. At some stage c.1815 she was told by Christian sooth-sayers that she would become the bride of the Messiah, whose return to Earth was imminently due. Nothing could be more aptly dramatic. Stanhope accepted her destiny; and settled down to wait. She found two noble and distinctive horses, which were carefully tended for years, awaiting the moment when the returned Messiah and his bride would ride forth to judge the world at the Second Coming.

Excited prophecies of the End of the World can be found in any era,7 and were particularly rampant in Europe in the febrile aftermath of the French Revolution and the prolonged Napoleonic wars. At different times, individuals have claimed to be the returned Messiah – or to be closely connected with such a figure – or to know the exact date of the Second Coming. In the Christian tradition, it is rare for women to claim divinity or near-divinity on their own account. However, in 1814 Joanna Southcott, aged 64, announced that she was pregnant with the new Messiah and, briefly, attracted a large following, until she died of a stomach tumour, without producing the miraculous child. During her lifetime, she had instituted her own church, with a male minister to officiate at the services. And the Southcottian movement has survived as a small sect, with numerous twists and turns in its fortunes, into the twenty-first century.8

By contrast, Lady Hester Stanhope’s vision remained an individual destiny. Visitors approached her in her Lebanese retreat, impressed by her magus-like reputation. But Stanhope did not attempt to found a church or a supporting movement. Instead, she settled in to wait patiently. That response is a not uncommon one when a divine revelation is not immediately realised. True believers keep faith. It is the timing, not the vision, which is inaccurate. So the answer is to wait, which is what Stanhope indomitably did. Living initially in first one and then another disused monastery, she retreated eventually to a conical hill-top site with panoramic views at Joun, eight miles (13k) inland from Sidon. There she lived as the de facto local magnate. She was accepted within the religious mix of Muslim, Christian and Druze communities that has long characterised the Lebanon; and she tried to protect the Druze from persecution on grounds of their distinctive blend of Islam, gnosticism and neo-platonism. Doctrinal rigidity was very far from her personal mindset.

Only with time did Stanhope become a real recluse. By the mid-1830s, her original English companions had either died or returned home. Her funds ran low and she was besieged by creditors. The servants, allegedly, began to steal her possessions. Lady Hester Stanhope received her few last visitors after dark, refusing to let them see more than her face and hands. Reportedly, she suffered from acute depression. The Messiah did not come. Yet there was a sort of glory in her faithfulness. Her life’s trajectory was utterly distinctive, not one that could be emulated by others. Buoyed by sufficient funds, she made an independent life in an initially strange country, far from the political salons of early nineteenth-century London. And she persisted, even when impecunious. Stanhope died in her sleep aged 63, still awaiting her destiny – and having made her own legend.

ENDNOTES

1 There are many biographies: see e.g. K. Ellis, Star of the Morning: The Extraordinary Life of Lady Hester Stanhope (2008); and a pioneering survey by C.L.W. Powlett, The Life and Letters of Lady Hester Stanhope (1897).

2 B. Hill, Women Alone: Spinsters in England, 1660-1850 (2001).

3 J. Austen, Persuasion (1817/18; in Harmondsworth, 1980 edn), pp. 165-7, 200.

4 N. Phillips, Women in Business, 1700-1850 (Woodbridge, 2006); H. Barker, Family and Business during the Industrial Revolution (Oxford, 2017).

5 E. Chalus, Elite Women in British Political Life, c.1754-90 (Oxford, 2005).

6 For a sympathetic account, see https://womeninarchaeology.com/2016/05/05/lady-hester-lucy-stanhope-the-first-modern-excavator-of-the-holy-land/.

7 J.M. Court, Approaching the Apocalypse: A Short History of Christian Millenarianism (2008); C. Wessinger (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Millenialism (Oxford, 2011).

8 J.K. Hopkins, A Woman to Deliver her People: Joanna Southcott and English Millenarianism in an Era of Revolution (Austin, Texas, 1982); J.D.M. Derrett, Prophesy in the Cotswolds, 1803-1947 (Shipston-on-Stour, 1994); P.J. Corfield, Power and the Professions in Britain, 1700-1850 (1995; 2000), pp. 106-8. 124, 139; J. Shaw, Octavia, Daughter of God: The Story of a female Messiah and her Followers (2012).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 116 please click here