MONTHLY BLOG 46, THE HISTORY OF THE HAND-SHAKE

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2014)

Not everyone shakes hands. But those who do are expressing an egalitarian relationship. As a form of greeting, the handshake differs completely in meaning from the bow or curtsey, which display deference from the ‘lowly’ to those on ‘high’.1 In one Jane Austen novel, a fearlessly ‘modern’ young woman extends her hand to a young man at a crowded party. Of course, it is Marianne Dashwood, the embodiment of ‘sensibility’. She has just re-encountered the errant Willoughly, long after he has ended their unofficial courtship. Marianne immediately holds out her hand, claiming him as an intimate friend. But he avoids her gesture. Marianne then exclaims ‘in a voice of the greatest emotion: “Good God! Willoughby, what is the meaning of this? … Will you not shake hands with me?”’. He cannot avoid doing so, but drops her hand quickly. After a few short exchanges, Willoughby then leaves ‘with a slight bow’.2 He has dropped her. Their body language says it all.

There is a particular poignancy in this scene. In this era, men and women who were not related to one another would not ordinarily touch hands as a form of greeting. But, of course, lovers might do so. No wonder that a mere touch was so powerful when it was so rare. (And it retains its appeal today in romantic mythology and countless pop songs: I Wanna hold your Hand!)3 Shakespeare, as ever, had known the scene. Romeo understands the intimacy implied when he takes Juliet’s hand in a dance, as does she: ‘And palm to palm is like holy palmer’s kiss’.4

Even more definitively, a couple would touch hands in a marriage ceremony (even allowing for the many varieties of ritual associated with weddings).5 The wording was clear. ‘Taking someone’s hand in marriage’ is an ultimate symbol of good faith, along with the exchange of rings which remain visible on the hand. These are public signs of personal commitment. An earlier poetic expression also offered an endgame variant, in the form of a final handshake. Michael Dayton’s Sonnet LXI (1594) which starts ‘Since there’s no help, come let us kiss and part’ invites the parting lovers to: ‘shake hands for ever, cancel all our vows’.

At the same time, a close handshake also has a set of commercial connotations. When two traders agree upon a contract, they may indicate the same by a handshake. However unequal they may be in wealth and commercial status, for the purposes of the deal they are equals, both pledging to fulfil the bargain. It constitutes a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ – upheld by personal honour. The same etiquette applies in making a bet.

Hence reneging upon a wager or deal sealed with a personal handshake is viewed as particularly heinous. The loser may even litigate for redress. Today the American Sports World News reports rumours that Charles Wang, the majority owner of the New York Islanders ice-hockey team, is being sued for $10 million by hedge-fund manager Andrew Barroway. Wang’s crime? He had allegedly reneged on a handshake pact to sell his Islanders franchise to Barroway.6

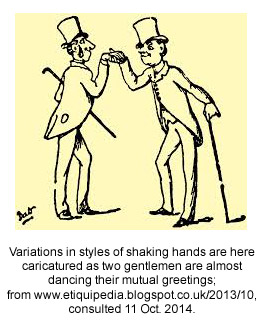

Typically, a handshake is a brief and routine affair, usually but not invariably with the right hand. True, there are variants. The prolonged handshake plus a clasp of the recipient’s upper arm by the shaker’s other hand is a gesture of special warmth – stereotypically undertaken by gregarious American politicians.7

Or there is the Masonic handshake. It gives a secret signal, allowing members of a separate society to identify one another. Apparently, there are many variants of the Masonic handshake, denoting differences in rank within the organisation. That information is rather depressing, since the handshake is, in principle, egalitarian. Nonetheless, it shows the potential for stylistic variation, from the firm muscular grip to the fleeting touch-and-drop.

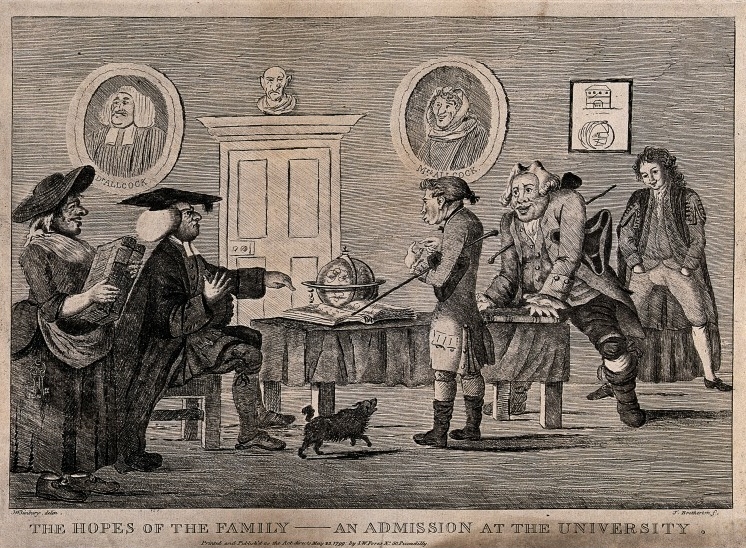

Gradually, routine British styles of greeting began to incorporate the handshake. It was most common among civilian men of similar middle-class standing. By contrast, the toffs stuck with their traditional bowing and curtseying. Meanwhile, hand-shaking was rare among workers in ‘dirty’ trades and industries, because people in unavoidably grimy jobs usually tried to contain rather than to spread the dirt. The emblem of two clasped hands nonetheless appeared proudly on various trade union banners, as a pledge of solidarity.

Gradually, routine British styles of greeting began to incorporate the handshake. It was most common among civilian men of similar middle-class standing. By contrast, the toffs stuck with their traditional bowing and curtseying. Meanwhile, hand-shaking was rare among workers in ‘dirty’ trades and industries, because people in unavoidably grimy jobs usually tried to contain rather than to spread the dirt. The emblem of two clasped hands nonetheless appeared proudly on various trade union banners, as a pledge of solidarity.

The advent of the social handshake was thus not uniform across all periods and classes. But it could be found, between close male friends, in Britain from at least Shakespeare’s time. Yet its subsequent spread has taken a long time a-coming. For example, in 1828 the anonymous author of A Critique of the Follies and Vices of the Age was still expressing displeasure at the new popularity of the handshake, including between men and women.8

One reason for some snobbish hostility, among polite society in Britain, was the association of this custom with the republican USA, where its usage became increasingly common after American independence. There were also connotations of support for the hand-shaking citizens of republican France from 1793 onwards. English visitors to the USA like the novelist and social commentator Frances Trollope thus waxed somewhat critical of the local mores. In 1832, she deplored the habit of hand-shaking between both sexes and all classes (albeit excluding the non-free).For her, this form of greeting was too bodily intimate, especially as ‘the near approach of the gentleman [ironically] was always redolent of whiskey and tobacco’.9

Ultimately, however, the snobs were routed. Old-style bowing and curtseying has generally disappeared, although hat wearers may still doff their hats to ladies. However, the twentieth century also produced another twist in the tale. Just as the hand-shake was becoming quite widely adopted in Britain by the 1970s, it was suddenly challenged by a new custom, imported from overseas. It is the continental kiss, in the form of a light clasp of the upper arms and a peck on the cheek (or, for the physically fastidious, an air-kiss). Such a manoeuvre would give good scope to a later Marianne Dashwood, who might grip an errant Willoughby in order to kiss him warmly. Nonetheless, be warned: whatever the greeting style, body language always provides ways of signalling the rejection as well as the offering of friendship.

1 See P.J. Corfield, previous monthly BLOG 45 ‘Doffing One’s Hat’. And for fuller discussion, see PJC, ‘Dress for Deference & Dissent: Hats and the Decline of Hat Honour’, Costume: Journal of the Costume Society, 23 (1989), pp. 64-79; also transl. in K.Gerteis (ed.), Zum Wandel von Zeremoniell und Gesellschaftsritualen: Aufklärung, 6 (1991), pp. 5-18; and posted on PJC personal website as Pdf/8.

2 J. Austen, Sense and Sensibility (1st pub. London, 1811): chapter 28.

3 The Beatles (1963).

4 W. Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet (written mid 1590s; 1597), Act 1, sc. 5. A palmer was a successful pilgrim, returning from the Holy Land bearing palms as a sign that the journey had been achieved.

5 A traditional ritual of ‘hand-fasting’, announcing a solemn public engagement, has also been updated for use today in pagan marriage ceremonies.

6 Sports World News on-line 12.Aug. 2014, at www.sportsworldnews.com/articles, consulted 11 Oct. 2014.

7 See e.g. John Travolta’s film portrayal of a notably touchy-feely American presidential candidate, based upon Bill Clinton, in Primary Colors (dir. Mike Nichols, 1998).

8 Anon., Something New on Men and Manners: A Critique of the Follies and Vices of the Age … (Hailsham, Sussex, 1828), p. 174.

9 F. Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832), ed. R. Mullen (Oxford, 1984), p. 83.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 46 please click here