PJC WEBSITE REVIEW/2 – THE DOCTOR’S DILEMMA (1906) BY GEORGE BERNARD SHAW

AT THE NATIONAL: LYTTLETON THEATRE (August 2012)

Viewed by PJC, with Tony Belton.

It’s a witty script and the audience was engaged throughout by this production of the Doctor’s Dilemma. Penelope laughed a great deal; and, having read Shaw’s play many times (as a historian of the professions), she was particularly delighted to see it performed at last on stage. Tony laughed moderately. The National Theatre’s production, directed by Nadia Fall, is handsomely staged and amusingly acted. Yet there’s no denying that there are problems with the play as a theatrical experience.

For a start, it’s very static. The characters come on stage and make debating points, each doctor espousing his favourite remedies. (Yes, the medical profession at this time is very male. The doctors are indubitably father figures). On the other hand, some plays are static but still work dramatically. Or do they? Many of Samuel Beckett’s famous plays are very static; but, in fact, his plays are not staged much these days. In a world full of ‘movies’, the ‘standies’ need an absolutely coruscating script to keep the audience’s attention.

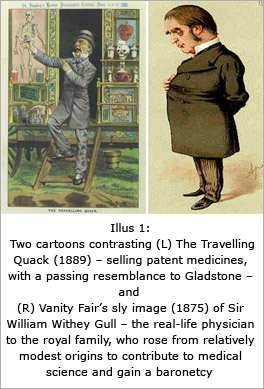

If there is not much action, what about character development? Dramas on stage or film often feature challenges to individuals who then undergo moral growth or, at very least, wise up to the ways of the world. Here again, Shaw is limited. His characters embody ideas. As a result, they offer the actors some splendid opportunities for satirical use of speech and body language. The surgeon Mr Cutler Walpole is a zealous advocate of his cutting craft and Robert Portal gives this character a splendidly crisp diction and purposive walk. These mannerisms set him apart from the sleekly languid, plumply prosperous, and discreetly well-bred physicians at the very summit of the profession – who are all distinguished from the seedy and ailing general practitioner Dr Blenkinsop, played with shuffling pathos by Derek Hutchinson. There’s a good deal of comedy and sharp observation in the by-play between these medical men. But the point is that they are all recognisable types, whose conversational gambits don’t ask the actors to scale any emotional heights.

On the other hand, again, how essential is character development to make good theatre? There are playwrights – Samuel Beckett again comes to mind – who focus upon the keen interplay of ideas and words, not the unfolding of individual or community transformation. After all, there is no general rule that must apply to theatre – other than the willing suspension of disbelief.

On the other hand, again, how essential is character development to make good theatre? There are playwrights – Samuel Beckett again comes to mind – who focus upon the keen interplay of ideas and words, not the unfolding of individual or community transformation. After all, there is no general rule that must apply to theatre – other than the willing suspension of disbelief.

So without much action or character development, what does Shaw’s Doctor’s Dilemma provide instead? The answer is a fairly exiguous plot and a crackling wit, chiefly at the expense of the medical profession. Shaw considers medicine to be a human – and hence fallible – art rather than a would-be infallible science. The doctors chaff each other, while the audience is invited to laugh at them all. Each eminent doctor has his own pet diagnosis-and-remedy, which he repeats in and out of season. For the surgeon Cutler Walpole, the problem is blood poisoning and the required cure is his own specialist operation. For the newly knighted Sir Colonso Ridgeon, who is genially played by Aden Gillett, the key treatment for tuberculosis is his own special serum to stimulate the body’s ‘phagocytes’. For the patrician Sir Ralph Bloomfield Bonington (Malcolm Sinclair), the solution is much simpler: ‘find the germ and kill it’, with whatever anti-toxin that comes to hand. And the chorus is rounded out by a veteran physician, Sir Patrick Cullen (Jonathan Coote), who genially remarks of each new invention that he has ‘seen it all before’.

Underpinning the humour is Shaw’s conviction that all learned professions are, at heart, a conspiracy against the laity. There is an element of truth in the charge, since much expertise remains far too specialised for the general public to check at all easily. And certainly doctors, like everyone, can benefit from a bit of humility. Indeed, a number of professionals collect jokes at their own expense, as an antidote to the high seriousness of their everyday calling. Yet medicine as a discipline does, in fact, progress. Both its science and its art (in terms of improved bedside consultation) have generally improved over time. Doctors do not just spot their own specialism every time. They are endlessly checked and assessed – and so forth – in a collective project.

So Shaw’s sallies at the expense of the individual doctor’s medical knowledge don’t hit home today with major force. The related issue – the dilemma at the core of the play – is, however, a very real one. It focuses upon the allocation of scarce medical resources. With the best will in the world, not everyone can have exactly the same level of care. But again, decisions about resource allocation are not made these days either solely or even chiefly by individual doctors. Instead, it is the entire system of the National Health Service, complete with the input from NICE – the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence – and from the ever-meddling politicians, which remains a valid subject for satire as well as for celebration, à la Danny Boyle.

Finally, Shaw launches two subsidiary shafts of humour. One targets the bohemian artist, who is gifted, charming, and careless of conventional morality. Louis Dubedat (played Tom Burke, looking suitably Byronic) insouciantly borrows money that he can’t repay and cheerfully deceives women. He was obviously a type known to Shaw, who portrayed another variant in the form of Albert Doolittle in Pygmalion (1912). The satire is affectionate, teasing also the conventional doctors who don’t know how to deal with Dubedat. He dies of tuberculosis on stage, while checking eagerly that the intruding journalist is present to record his last words in praise of Art and Beauty.

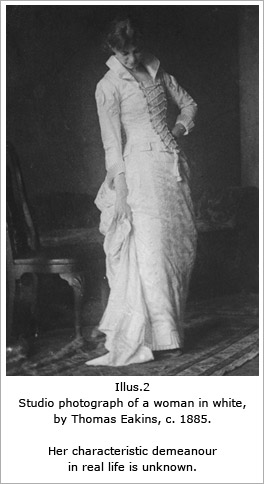

And lastly, Shaw explores the character of the outwardly meek and innocent Victorian wife, who tries to manipulate men while pretending unawareness of her sexual appeal. Jennifer Dubedat, played by Genevieve O’Reilly with voluptuous appeal, looks in public like a terrestrial impersonation of the ‘Angel in the House’ of poetic fame. Her gaze falls down, her dress is gleamingly white, her voice is caressing, her pose supplicant. She appeals, as if artlessly, to men’s chivalry. Shaw again essays a number of variants of this character. One is named only as ‘The Lady’ in The Man of Destiny (1896). When she murmurs, wide-eyed: ‘I show my confidence in you’, the male of the species should beware. The clever woman, disguised as an ingénue, challenges without appearing to challenge the powerful, acerbic man of the world, who half sees through her but can’t resist. It’s a female pose that’s not so common today, post-women’s lib. But it’s still done, sometimes naturally, sometimes not.

Given that the contest between the beguiling female and the suspicious male is intrinsically theatrical, it works well on the stage. And there is a moment of real frisson, which must have been particularly shocking in 1906 when the play premiered. Newly widowed, Jennifer Dubedat exits immediately, only to return wearing not black but a sumptuous crimson evening dress, which displays to the full her bosomy charms. The assembled medical men gasp.

Given that the contest between the beguiling female and the suspicious male is intrinsically theatrical, it works well on the stage. And there is a moment of real frisson, which must have been particularly shocking in 1906 when the play premiered. Newly widowed, Jennifer Dubedat exits immediately, only to return wearing not black but a sumptuous crimson evening dress, which displays to the full her bosomy charms. The assembled medical men gasp.

She wants to bear witness to her past happiness, in tribute to the high ideals of Art. Pollyanna-style, she burbles: ‘Life will always be beautiful to us; death will always be beautiful to us. May we shake hands on that?’ Her deliberately maintained self-delusions about her late husband are absurd yet also real. In the play, she is left unenlightened and still happy.

Where does that leave Shaw? His dreams of replacing Shakespeare as the national bard won’t come true. Yet Shaw was a great script-writer. His plays are not naturals for the big stage today; but, with sharp editing and fast-paced high-quality productions, they would make great TV dramas. Come on, programme-commissioners, give us a big Shaw season on the box. As one celebrated actor recently confirmed to us: ‘Shaw’s texts read wordy but act well’. He dramatises life’s ever-recurring dilemmas and the constant need for human judgements. Let’s have lots more Shavian prompts to laughter and thought.

To read other reviews, please click here.