PJC WEBSITE REVIEW/9 OSCAR WILDE, THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST (1895)

performed by Two Gents

at the Tara Arts Theatre,

Earlsfield viewed on 9 March 2019

by Penelope J. Corfield

after viewing by PJC and Tony Belton

Every new production of a classic play offers the chance of discovering something more about the drama – and about its message. This iteration was no exception to that rule. Wilde’s brilliant comedy was performed by two unknown young actors, who shared all the parts between them, with a bit of help from the audience. It could have been an embarrassing disaster. In fact, we were treated to an acting tour de force. The show was both magnetic and funny – and, judging from the prior comments of various members of the audience, it wowed a number of youngsters who were not traditional theatre-goers.

One reason for this scintillating success was the actors’ reliance on the power of Wilde’s dialogue. Quite a few lines were cut. (I was sorry to miss the butler’s announcement that cucumbers were not available in the market ‘even for ready money’). But in general the two actors gave us plenty of authentic Wildean witticisms, clearly enunciated throughout and projected via an array of regional accents and varied intonations to differentiate one character from another. That effect was also achieved by actorly effective body language. The commanding Lady Bracknell and her daughter Gwendolen did not fail to command. The simpering Cecily Cardew simpered. Canon Chasuble was unctuous. Miss Prism was outwardly prim yet not-so-secretly aflame with desire for the Canon. And so forth.

As the two actors raced around the small stage, with its minimal props, they cleverly conjured up the different scenes. At times, they verbalised some of Wilde’s stage commands. ‘[Enter Lane]’. It was all done very lightly, without halting the onwards flow of the play’s four Acts, which were run together into one ninety-minute show. The result really concentrated attention upon Wilde’s sustained satire of social artifice.

Throughout, too, the actors interacted genially with the audience. We were invited to make rural sounds to signify that the stage action was shifting to Jack Worthing’s country house in Hertfordshire: cue an assortment of baas, moos, clucks and birdsong. (It sounds naff but was very funny). And, at times, individual members of the audience were led onto the stage as stand-ins. So an unknown young woman became the recipient of Lady Bracknell’s fashion advice (Act IV). She pronounced loftily that: ‘Style largely depends on the way the chin is worn. They are worn very high, just at present’. The unknown young woman laughed and duly raised her chin – and we could all see the instant difference in her self-presentation. A moment of magic.

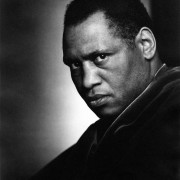

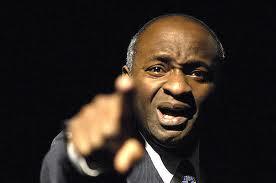

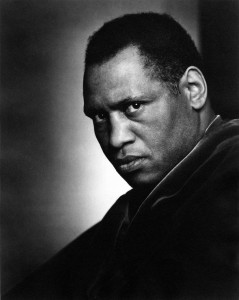

The two women actors who acted and coordinated this collective evening of mirth were modestly unnamed on the short flyer. They were identified merely as taking part in a Two Gents Production, which a web-search reveals to be a cross-cultural touring company, based in London.1 It may be assumed from their relative youth that these young women actors are relative beginners on stage. Certainly, the minimalist programme did not parade a back-list of their past performances in other shows. Somehow, however, these two have already become consummate stage professionals. At various points, their performances made easy and charming references to their British-African heritages. But they also showed us the universality of theatre and human passions. The diverse audience responded with laughter and enthusiasm. Since the performers went unnamed, here is a large picture of them instead – and (Two Gents/Tara Arts) they should have their names on the flyer next time. [STOP PRESS: Later identified from L to R as Kudzanayi Chiwawa and Ayesha Casely-Hayford]

Lastly, then, what of Wilde’s message to his audiences? He is clearly satirising the outward affectations of smart society, with its cult of money, status, conformity, hypocrisy, and insincerity. He also wants us to understand that, beneath the glittering social surface, deep feelings continue to bubble away. One of those subterranean passions, unsurprisingly, is sexual desire. This production underlines that point with vigour. At one point, each actor manages with great agility to hug herself as though wrapped in her lover’s arms, smacking her lips noisily, while the other, side by side, does the same. And, at another moment, the two of them, in the guise of Miss Prism and Canon Chasuble, disappear beneath a coverlet to have noisy and energetic sex, with much growling, yapping and lascivious sighing.

Lastly, then, what of Wilde’s message to his audiences? He is clearly satirising the outward affectations of smart society, with its cult of money, status, conformity, hypocrisy, and insincerity. He also wants us to understand that, beneath the glittering social surface, deep feelings continue to bubble away. One of those subterranean passions, unsurprisingly, is sexual desire. This production underlines that point with vigour. At one point, each actor manages with great agility to hug herself as though wrapped in her lover’s arms, smacking her lips noisily, while the other, side by side, does the same. And, at another moment, the two of them, in the guise of Miss Prism and Canon Chasuble, disappear beneath a coverlet to have noisy and energetic sex, with much growling, yapping and lascivious sighing.

To escape those stultifying norms of high society, both the two leading male characters – the ‘solid’ Jack Worthing and the dandy Algernon Moncrieff (who turn out to be brothers) – have recourse to secret lives. They have created elaborate fictions which enable them to live one life in the countryside and another in town. Algernon has to make constant visits to a chronic invalid friend, named Bunbury, while Jack has to rush to the rescue of his ‘wicked’ brother Earnest, who is always getting into scrapes.

It is not hard to believe that their stratagems constituted a dramatisation of Wilde’s own awareness of living with a divided self and divided sexuality. The play, performed in triumph in 1895, was the last he ever wrote, immediately before he became embroiled in legal entanglements, which ended with his prosecution and imprisonment for ‘gross indecency’. Within the effervescent drama, there is no hint of tragedy to come. Nor does the plot conclude with anything as heavy as a call for social change, except by implication. There is, however, a covert appeal for friendship, sincerity, tolerance, the avoidance of subterfuge, and the capacity for individuals to live truthfully, in the light of their true natures.

Yes, Oscar Wilde: yes indeed. But, as he knew as a dramatist and then reaffirmed in prison, it’s not an easy task to reconcile all interests, all passions, all individual roles and identities. Toleration is a high social art, relying upon both law and custom; and it has to be relearned and lived positively in every generation.

1 For Two Gents’ productions and workshops, see http://www.twogentsproductions.co.uk. This production was supported by Tara Arts. Compliments are also due to the co-directors, identified subsequently as Arne Pohlmeier and Tonderai Munyevu.

To read other reviews, please click here.

In this case, the scenes are all set in one Glasgow tenement. And the cast speak throughout in a no-holds-barred plebeian Glaswegian accent, which adds verisimilitude but which completely baffled an American sitting close to us in the audience. All well and good. Much of the action was symbolic and it was possible to trace the fast-shifting patterns of power and submission from the actors’ magnificently visceral body-language.

In this case, the scenes are all set in one Glasgow tenement. And the cast speak throughout in a no-holds-barred plebeian Glaswegian accent, which adds verisimilitude but which completely baffled an American sitting close to us in the audience. All well and good. Much of the action was symbolic and it was possible to trace the fast-shifting patterns of power and submission from the actors’ magnificently visceral body-language.

Is there any hint of an escape-route for these educated but melancholy people, deep in nineteenth-century Russia’s remote provinces? They had no electronic media to link them to friends around the world. They could not sign up to courses of distance learning. And they could not all manage to move to Moscow, where, even so, they might end up as self-deceiving mediocrities like the professor. Chekhov does not suggest anything positive. He himself was a chronically busy and active person. So his life’s message might be to discover one’s chosen metier and to work at it. But how to find and then to cultivate it?

Is there any hint of an escape-route for these educated but melancholy people, deep in nineteenth-century Russia’s remote provinces? They had no electronic media to link them to friends around the world. They could not sign up to courses of distance learning. And they could not all manage to move to Moscow, where, even so, they might end up as self-deceiving mediocrities like the professor. Chekhov does not suggest anything positive. He himself was a chronically busy and active person. So his life’s message might be to discover one’s chosen metier and to work at it. But how to find and then to cultivate it? Illustrations: (1) Birch woods in Sosnovka Park, St Petersburg, Russia from

Illustrations: (1) Birch woods in Sosnovka Park, St Petersburg, Russia from