MONTHLY BLOG 18, IN PRAISE OF MEMORY

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2012)

Try living without it. In healthy humans, memory works non-stop from birth to death. That means that it can work, unprompted, for over a century. Memory automatically tells us who we are (short of mental illness or accident). It simultaneously supplies us with our personal back-story and locates us within a broad framework picture of the world in which we have lived to date. Our capacity to think through time, and to remember things that happened long ago, constitutes a major characteristic of what it means to be human.

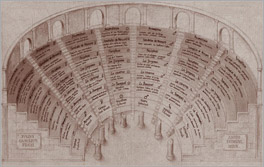

As such, the power of memory is an ancient, not to say primaeval, capacity. It’s entwined with consciousness. But it also operates at instinctual levels, as in muscle memory. With its multiple resources, memory is notably multi-layered. It can be cultivated consciously. A host of mnemonic systems, some very ancient, offer systems to help the mind in storing and retrieving a huge ragbag of ideas and information.1 Giulio Camillo’s beautiful Theatre of Memory (shown in Fig. 1) is but one example.2 It’s a nice imaginary prospect of the inside of the human cranium.

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone.

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone.

Given its primaeval origins, the human capacity to remember notably predates the invention of calendars. Such time-measuring and time-referencing devices are the products, not the first framers, of memory. As a result, we don’t habitually remember by reference to precise dates and times, with the exception of special events or consciously learned information. Nor do we retain everything. Forgetting selectively is as much a human capacity as remembering. Too much and we’d suffer from information overload.

The combination of remembering and forgetting, both individually and collectively, has some significant implications. Not only does memory fade but, unkindly, it also plays tricks. Details that we think we remember with great confidence can turn out to be false. My own deceitful memory has just given me a shock, which I’ve taken to heart since I pride myself on my powers of recollection. One of my clear recollections of the student protests in 1969 (which I wrote about in my January discussion-piece) has turned out to be erroneous, at least in one significant detail. At a lunch-time protest meeting at Bedford College in 1969 or early 1970, an ardent young postgraduate urged those present to capture the Principal’s office today, in order to overthrow capitalism tomorrow. I am certain that the event took place and that the speech was greeted with cheers (and some silent scepticism – mine included).

However, my memory has over time fabricated an erroneous identity for the speaker. I met the person in question last week – now a Labour peer in the House of Lords – and reminded her of the episode, expecting some shared laughter at the ambitious scope of youthful ideals. But she did not attend Bedford College nor had she ever visited it. Moreover, she had always shared my critique of the student utopianism of the later 1960s. I was wrong on a central point, which I’d convinced myself was correct. Could I even be sure that the protest meeting took place at all? Collapse of stout party – myself.

And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

A second lesson is that human gossip and chatter is an essential part of the process of checking and cross-checking memories. Such retrospective discussions (‘She said … ; and then I said … ; and then she replied …’) often seem rambling and inconsequential. They are, however, consolidating the stuff of memory. It works for communities as well as for individuals. Indeed, talking, taking stock, and remembering together is helpful, particularly after experiences of disasters which should not be forgotten in silence. Vera Schwarcz’s powerful study Bridge across Broken Time makes that point in its title.3 Memory, with all its faults, allows for the possibility of understanding the past and overcoming traumas. Conversely, the negative effects of buried memories for starkly dislocated communities reverberate through successive generations.

So my final point: here come the historians. The fallibility of unvarnished memory encouraged the first production of memory aids, such as written and numerical records, and calendrical calculations. And over time humans have generated an immeasurable cornucopia of data and documentation, which is far beyond the capacity of any individual mind to store. It is now a collective resource. Historians don’t replicate human memory. Indeed, they share its fallibilities. But, collectively, they join the task of storing, cross-checking, correcting, ordering, and evaluating a past that goes beyond individual memory.

1 For a stirring analysis, ranging from classical Greece to the European Renaissance, consult the classic by Frances A. Yates, The Art of Memory (1966). A recent contribution to the memory bug is also provided by Joshua Foer, Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything (2011).

2 For the philosopher Giulio Camillo (c.1480-1544), see K. Robinson, A Search for the Source of the Whirlpool of Artifice: The Cosmology of Giulio Camillo (Edinburgh, 2006).

3 Vera Schwarcz, Bridge across Broken Time: Chinese and Jewish Cultural Memory (New Haven, 1998).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 18 please click here