If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2022)

|

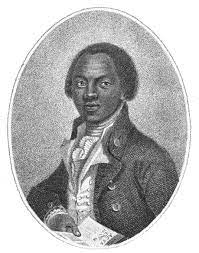

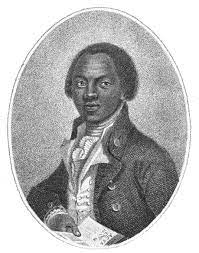

Olaudah Equiano (c.1745-97),

former child slave whose public testimony

made a strong contribution to the British

campaign to abolish the slave trade.

|

Georgian Britain is known for its historic participation in the transportation of captive Africans from their homeland to the New World. There the involuntary migrants were detained as slaves. Set to work in the sugar plantations, they were viewed by their ‘masters’ as an ultra-cheap labour-force. But familiar references to the ‘slave trade’ can blunt appreciation of the horrific reality. The financiers, merchants, dealers, ship’s captains and crews were all colluding in – and profiting from – a brutal demonstration of power inequalities. European traders and opportunistic African chiefs, fortified with guns, whips, and money, preyed upon millions of unarmed victims. They were exiled abruptly from everything that they knew: not only from families, friends, and communities but also from their languages, lifestyles, and belief systems. It was trauma on an epic scale.1

However, Georgian Britain was also known, especially as time passed, for a growing tide of opposition to the trade.2 The egalitarian Quakers were among the first to declare their repugnance.3 But, increasingly, others were galvanised into opposition. People were shocked to learn of the dire conditions in which the Africans were kept on board ships as they navigated the notorious Middle Passage across the Atlantic.4

One eloquent testimony came from the Anglican clergyman, John Newton (1725-1807). As a young man, he was involved in the slave trade, which he later abhorred. His resonant hymn Amazing Grace (1773, pub. 1779) explains that he once ‘Was blind, but now I see’. Newton was probably alluding to his spiritual awakening, which led him to take holy orders. Yet the phrase applied equally well to his change of heart on the slave trade.

Others found that their eyes were similarly opened, especially once the new Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade (founded 1787) began its energetic campaigning. Among those aroused to protest were numerous middle- and upper-class women. In this era, they had no right to vote; yet that did not stop them from organising petitions, lobbying ministers, and joining anti-slavery groups.5

In 1700 there was virtually no public debate in Britain about the rights or wrongs of the trade. Yet by 1800 opposition was strengthening amongst the wider public as well as within parliamentary circles. Supporters of slavery and the slave trade had some important assets on their side. Those included: tradition; profits; strong consumer demand for sugar and rum; and (before 1807) the law.6 However, the pro-slavers were forced increasingly onto the defensive.

An abolitionist tract in 1791 argued forcefully that: ‘We, in an enlightened age, have greatly surpassed in brutality and injustice the most ignorant and barbarous ages: and while we are pretending to the finest feelings of humanity, are exercising unprecedented cruelty.’7 People should ‘wise up’ to the injustices that underpinned their consumer lifestyles – and live up to the claims of the new Zeitgeist. The same case was made by the African abolitionist, Olaudah Equiano, himself a former slave. Freedom for ‘the sable people’, he declared, was essential in this era of ‘light, liberty, and science’ (1789).8

And legal changes did follow. Notwithstanding intensive lobbying from the slave traders and the West Indian plantation-owners, the British parliament legislated in 1807 to ban British ships from participating in the slave trade; and (a generation later) to abolish slavery as a valid legal status within Britain and its colonies. A separate act in 1843 extended the prohibition to India, whose governance was then overseen by the East India Company.

These declarations of principle were massively significant. And Britain was not alone in rejecting slavery. Personal unfreedom was increasingly held to be unjustifiable in any humane and civilised society. As is well known, it took a bruising civil war (1861-5) to abolish slavery in the USA. But the Southern slave-owning states did eventually lose.

Over time, moreover, world-wide opinion has collectively swung into line. In 1926 the new League of Nations agreed an international treaty to ban slavery and the slave trade. And in 1949, the United Nations General Assembly updated that commitment with a further emphatic rejection of all people-trafficking.9 In no country since 1981 has slavery been legal.10

Yet there was, throughout the nineteenth century, as there remains today, a gigantic problem with these radiant declarations of principle: enforcement.

Which authorities were to police these prohibitions, and with what powers? Nation-states can potentially check upon things within their own bounds. Yet cross-border people-trafficking raises complex practical and jurisdictional issues. As a result, slavery resolutely survives. There are problems of definition as there are many diverse cases of unfreedom, whether established through physical force, psychological or financial coercion, debt bondage, abuse of personal vulnerability, outright deception, or reliance upon customary practices.

Today there are almost 50 million citizens world-wide living in conditions of slavery. Very many are women or young children, including those trapped into providing sexual services. Some 27.6 million individuals undertake forced labour, while another 22 million are caught in forced marriages (which are, legally, a different category of abuse). Countries with notably large numbers of modern-day slaves include, in Eurasia and the Far East: China, India, Indonesia, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia and the Philippines; as well as, in Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria.11

But no region of the world can be complacent. Heartless people-traffickers bring their human cargo everywhere, providing cheap labour and/or cheap sexual services. How does this infamous state of affairs still continue? People traffickers are motivated by the lure of high profits and enabled by the weaknesses of national and international enforcement.

Equally, however, the ‘open secret’ of modern-day slavery is aided by the ‘blindness’ of today’s consumers. They are as keen to acquire cheap goods and services as people in the Georgian era were to drink cheap Caribbean rum and to sweeten their tea with Caribbean sugar. Moreover, when many consumers today are suffering from the rising cost-of-living, they may obviously lack time and enthusiasm to give a stringent moral audit to determine the source of every item of food, clothing, housing, technology and services.

So that is where campaigners with energy for the abolitionist cause continue to play a vital role. In the early nineteenth century, reformers like William Wilberforce (1759-1833)12 were ridiculed for their ‘do-gooding’. Yet the Abolitionists’ campaigning successfully propelled the cause of anti-slavery from a minority issue to the forefront of politics.

Activists today try equally valiantly to highlight the predicament of people trapped in slavery – to urge better preventive action – and to help survivors who manage to break free. There are numerous admirable church groups and non-governmental organisations devoted to these tasks. The longest continually-surviving NGO is Anti-Slavery International, founded in Britain in 1839.13 It needs great reserves of optimism and persistence, as its hydra-headed foe is proving hard to eradicate. There are perennial arguments between vested commercial interests and the civic need to regulate the labour market, so that the workforce gets a fair deal from its labour.

Celebrating anti-slavery was boosted in the UK in 2010 by the introduction of 18 October as Anti-Slavery Day. (The UN’s international equivalent date is 2 December). Such events signal an official reaffirmation of principle – and a desire to educate the public. In the same spirit, a number of European and African governments (including the UK under Tony Blair) have publicly apologised for their country’s historic role in the slave trade. Some seaports, banks, and churches have done the same. And continuing discussions explore constructive and culturally-sensitive means of acknowledgement and reparation.14 (Far from all long-term outcomes of the trade are disastrous!)

Public attitudes are also stirred by direct testimony from former slaves. In eighteenth-century Britain, the Nigerian-born Olaudah Equiano15 was not the only African to support the Abolitionists. But he became the best known, o the strength of his personal message. Himself a former child slave, who had been taught to read and write by one of his ‘masters’, he managed to purchase his freedom. Eventually Equiano became a respectable rate-payer in the City of Westminster,16 where he voted in parliamentary elections. He married an Englishwoman and raised a family. And he bore public witness. He lectured in all the major cities of England, Ireland and Scotland; and in 1789 he published his best-selling autobiography, entitled, with clever understatement, The Interesting Narrative.

Furthermore, Equiano’s career and his calm demeanor carried a further implicit message. His evident fellow humanity refuted all those who mistakenly believed that sub-Saharan Africans were innately ‘savage’ – constituting ‘inferior’ beings, who merited treatment as disposable beasts of burden. The lectures and writings of the gentlemanly, God-fearing Equiano could not in any way be deemed the work of a ‘savage’.

Theories that divided humanity into separate ‘races’, all with intrinsically different attributes, have had a long and complex history.17 Some continue to believe them to this day. In fact, it has taken a lot of research and debate to refute so-called ‘scientific racism’ and to establish the properties of the shared human genome, or genetic blueprint.18

Equiano himself simply bypassed any racist attitudes. Instead, he agreed with those who, like the Quakers, firmly asserted the oneness of all people. He believed in fellow feeling and human sharing. Thus he asked, rhetorically: ‘But is not the slave trade entirely a war with the heart of man?19

Reflecting upon Equiano’s contribution to the Abolitionist cause prompts a further thought for today. The world needs to hear many more testimonies from people who have themselves endured modern-day slavery. It is known to exist but remains hidden – deliberately on the part of the perpetrators. They don’t all today wield guns and whips (though some do). But they prey heartlessly, with the aid of money, threats, and secrecy, upon the world’s least powerful people.

Step forward, all former slaves who have the freedom to speak out – like Sir Mo Farah, the British long-distance runner.20 Tell the world how it happens! Blow open people’s ears, eyes and minds! The more that is known, the harder it is to keep these things secret; and the greater will be public pressure upon governments to enforce the long-agreed global prohibition of enslavement. The old slave trade was a historic crime against humanity. Time now to stop its iniquitous modern-day versions.

|

Logo of Anti-Slavery International:

see https://www.antislavery.org.

|

ENDNOTES:

1 An immense literature, drawing upon generations of international research, now makes it possible to estimate the scale of the enforced African diaspora and its wider impact. See esp. J.K. Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800 (Cambridge, 1998): S. Drescher, From Slavery to Freedom: Comparative Studies in the Rise and Fall of Atlantic Slavery (Basingstoke, 1999); D. Eltis, ‘The Volume and Structure of the Transatlantic Slave Trade: A Reassessment’, William & Mary Quarterly (2001), pp. 17-46; H. Thomas, The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440-1870 (2015); and all studies cited by these authors.

2 For their divided world-views, see P.J. Corfield, The Georgians: The Deeds and Misdeeds of Eighteenth-Century Britain (2022), pp. 41-70.

3 B. Carey and G. Plank (eds), Quakers and Abolition (Urbana, Ill., 2014).

4 M.B. Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History (2007); F. Wilker, Cultural Memories of Origin: Trauma, Memory and Imagery in African American Narratives of the Middle Passage (Heidelberg, 2017).

5 C. Midgley, Women against Slavery: The British Campaigns, 1780-1870 (1992); A. Hochschild, Bury the Chains: Prophets and Rebels in the Fight to Free an Empire’s Slaves (2005); re-issued as idem, Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2010); J.P. Rodriguez (ed.), Encyclopedia of Emancipation and Abolition in the Transatlantic World (2007; 2015); S. Drescher, Abolition: A History of Slavery and Anti-Slavery (Cambridge, 2009).

6 M. Taylor, The Interest: How the British Establishment Resisted the Abolition of Slavery (2020).

7 Anon. [William Fox], An Address to the People of Great Britain … (11th edn., London, 1791), p. [i].

8 O. Equiano, The Interesting Narrative: And Other Writings, ed. V. Carretta (1995), p. 233.

9 UN Resolution 317(IV) of 2 December 1949: also banned was any form of ‘exploitation or prostitution of others’.

10 The last country legally to abolish slavery (in this case, hereditary slavery) was Mauritania in West Africa, although the practice is believed still to survive clandestinely.

11 Estimates by the United Nations agency, the International Labour Organisation (ILO): https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/lang–en/index.htm

12 For Richard Newton’s satirical print of Wilberforce as ‘The Blind Enthusiast’ (1792), see British Museum Prints and Drawings no. 2007,7058.3; biography by J. Pollock, Wilberforce (New York, 1977); and sympathetic film Amazing Grace (dir. M. Apted, 2007).

13 Consult https://www.antislavery.org

14 M. Falaiye, Perception of African Americans on Reparation for Slavery and Slave Trade (Lagos, Nigeria, 2008); A.L. Araujo, Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade: A Transnational and Comparative History (2017).

15 J. Walvin, An African’s Life: The Life and Times of Olaudah Equiano, 1745-97 (2000); L. Walker, Olaudah Equiano: The Interesting Man (2017). The Nigerian-born Equiano was known in Britain for many years as Gustavus Vassa, a name which alluded to the Swedish Protestant hero Gustavus Vasa (1496-1560), as chosen by Equiano’s slave master. For further appreciation and commemoration, see the Equiano Society, founded 1996: https://equiano.uk/the-equiano-society

16 A blue plaque at 67-73 Riding House Street, London W1W 7EJ marks the site.

17 E. Barkan, The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concept of Race in Britain and the United States between the World Wars (Cambridge, 1992); P.L. Farber, Mixing Races: From Scientific Racism to Modern Evolutionary Ideas (Baltimore, 2011).

18 For further details, see PJC: ‘Talking of Language, It’s Time to Update the Language of Race’ (BLOG/36. Dec. 2013); ‘How Do People Respond to Eliminating the Language of Race?’ (BLOG/37, Jan. 2014); ‘Why is the Language of ‘Race’ Holding on for So Long, When It’s Based upon Pseudo-Science?’ (BLOG/38, Feb.2014); ‘As the Language of ‘Race’ Disappears, Where Does that Leave the Assault upon Racism?’ (BLOG/89, May 2018); ‘Celebrating Human Diversity within Human Unity’ (BLOG/90, June 2018): all posted within PJC website: https://www.penelopejcorfield.com/global themes/4.4.

19 Equiano, Interesting Narrative (ed. Carretta), p. 110.

20 As revealed in July 2022: see https://www.antislavery.org/modern-slavery-and-human-trafficking-in-the-uk-sir-mo-farah-story-is-a-lesson-for-us-all.

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 142 please click here

Good-looking, debonair, raffish, sexy, attractive to both men and women, a breezy poet, a dog-lover, a radical in his politics, supporting working-class interests at home and Greek independence overseas, and a man with a title – George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), seemed almost too amazing to be true.1 But add into the mix the further pertinent facts that he was chronically impoverished; that he had a deformed foot, which gave him pain and forced him to walk with a limp; that he took to travelling restlessly overseas; that his marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke was unhappy; that many of his affairs were also tormented and short-lived; that there were accusations of incest with his half-sister and marital violence; that, as a result, Byron was considered deeply controversial by respectable society; … and his story was not straightforward.

Good-looking, debonair, raffish, sexy, attractive to both men and women, a breezy poet, a dog-lover, a radical in his politics, supporting working-class interests at home and Greek independence overseas, and a man with a title – George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), seemed almost too amazing to be true.1 But add into the mix the further pertinent facts that he was chronically impoverished; that he had a deformed foot, which gave him pain and forced him to walk with a limp; that he took to travelling restlessly overseas; that his marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke was unhappy; that many of his affairs were also tormented and short-lived; that there were accusations of incest with his half-sister and marital violence; that, as a result, Byron was considered deeply controversial by respectable society; … and his story was not straightforward.