MONTHLY BLOG 105, Researchers, Do Your Ideas Have Impact? A Critique of Short-Term Impact Assessments

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2019)

|

Clenched Fist |

Researchers, do your ideas have impact? Does your work produce ‘an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia’? Since 2014, that question has been addressed to all research-active UK academics during the assessments for the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which is the new ‘improved’ name for the older Research Assessment Exercise (RAE).1

From its first proposal, however, and long before implementation, the Impact Agenda has proved controversial.2 Each academic is asked to produce for assessment, within a specified timespan (usually seven years), four items of published research. These contributions may be long or short, major or minor. But, in the unlovely terminology of the assessment world, each one is termed a ‘Unit of Output’ and is marked separately. Then the results can be tallied for each researcher, for each Department or Faculty, and for each University. The process is mechanistic, putting the delivery of quantity ahead of quality. And now the REF’s whistle demands demonstrable civic ‘impact’ as well.

These changes add to the complexities of an already intricate and unduly time-consuming assessment process. But ‘Impact’ certainly sounds great. It’s punchy, powerful: Pow! When hearing criticisms of this requirement, people are prone to protest: ‘But surely you want your research to have impact?’ To which the answer is clearly ‘Yes’. No-one wants to be irrelevant and ignored.

However, much depends upon the definition of impact – and whether it is appropriate to expect measurable impact from each individual Unit of Output. Counting/assessing each individual tree is a methodology that will serve only to obscure sight of the entire forest. And will hamper its future growth.

In some cases, to be sure, immediate impact can be readily demonstrated. A historian working on a popular topic can display new results in a special exhibition, assuming that provision is made for the time and organisational effort required. Attendance figures can then be tallied and appreciative visitors’ comments logged. (Fortunately, people who make an effort to attend an exhibition usually reply ‘Yes’ when asked ‘Did you learn something new?’). Bingo. The virtuous circle is closed: new research → an innovative exhibition → gratified and informed members of the public → relieved University administrators → happy politicians and voters.

Yet not all research topics are suitable to generate, within the timespan of the research assessment cycle, the exhibitions, TV programmes, radio interviews, Twitterstorms, applied welfare programmes, environmental improvements, or any of the other multifarious means of bringing the subject to public attention and benefit.

The current approach focuses upon the short-term and upon the first applications of knowledge rather than upon the long-term and the often indirect slow-fuse combustion effects of innovative research. It fails to register that new ideas do not automatically have instant success. Some of the greatest innovations take time – sometimes a very long time – to become appreciated even by fellow researchers, let alone by the general public. Moreover, in many research fields, there has to be scope for ‘trial and error’. Short-term failures are part of the price of innovation for ultimate long-term gain. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the history of science and technology contains many examples of wrong turnings and mistakes, along the pathways to improvement.3

An Einstein, challenging the research fundamentals of his subject, would get short shrift in today’s assessment world. It took 15 years between the first publication of his paper on Special Relativity in 1905 and the wider scientific acceptance of his theory, once his predictions were confirmed experimentally. And it has taken another hundred years for the full scientific and cultural applications of the core concept to become both applied and absorbed.4 But even then, some of Einstein’s later ideas, in search of a Unified Field Theory to embrace analytically all the fundamental forces of nature, have not (yet) been accepted by his fellow scientists.5 Even a towering genius can err.

Knowledge is a fluid and ever-debated resource which has many different applications over time. Applied subjects (such as engineering; medicine; architecture; public health) are much more likely to have detectable and direct ‘impact’, although those fields also require time for development. ‘Pure’ or theoretical subjects (like mathematics), meanwhile, are more likely to achieve their effects indirectly. Yet technology and the sciences – let alone many other aspects of life – could not thrive without the calculative powers of mathematics, as the unspoken language of science. Moreover, it is not unknown for advances in ‘pure’ mathematics, which have no apparent immediate use, to become crucial many years subsequently. (An example is the role of abstract Number Theory for the later development of both cryptography and digital computing).6

Hence the Impact Agenda is alarmingly short-termist in its formulation. It is liable to discourage blue skies innovation and originality, in the haste to produce the required volume of output with proven impact.

It is also fundamentally wrong that the assessment formula precludes the contribution of research to teaching and vice versa. Historically, the proud boast of the Universities has been the integral link between both those activities. Academics are not just transmitting current knowhow to the next generation of students but they (with the stimulus and often the direct cooperation of their students) are simultaneously working to expand, refine, debate, develop and apply the entire corpus of knowledge itself. Moreover, they are undertaking these processes within an international framework of shared endeavour. This comment does not imply, by the way, that all knowledge is originally derived from academics. It comes indeed from multiple human resources, the unlearned as well as learned. Yet increasingly it is the research Universities which play a leading role in collecting, systematising, testing, critiquing, applying, developing and advancing the entire corpus of human knowledge, which provides the essential firepower for today’s economies and societies.7

These considerations make the current Impact Agenda all the more disappointing. It ignores the combined impact of research upon teaching, and vice versa. It privileges ‘applied’ over ‘pure’ knowledge. It prefers instant contributions over long-term development. It discourages innovation, sharing and cooperation. And it entirely ignores the international context of knowledge development and its transmission. Instead, it encourages researchers to break down their output into bite-sized chunks; to be risk-averse; to try for crowd-pleasers; and to feel harried and unloved, as all sectors of the educational world are supposed to compete endlessly against one another.

No one gains from warped assessment systems. Instead, everyone loses, as civic trust is eroded. Accountability is an entirely ‘good thing’. But only when done intelligently and without discouraging innovation. ‘Trial and error’ contains the possibility of error, for the greater good. So the quest for instant and local impact should not be overdone. True impact entails a degree of adventure, which should be figured into the system. To repeat a dictum which is commonly attributed to Einstein (because it summarises his known viewpoint), original research requires an element of uncertainty: ‘If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called “research”, would it?’8

ENDNOTES:

1 See The Research Excellence Framework: Diversity, Collaboration, Impact Criteria, and Preparing for Open Access (Westminster, 2019); and historical context in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Research_Assessment_Exercise.

2 See e.g. B.R. Martin, ‘The Research Excellence Framework and the “Impact Agenda”: Are We Creating a Frankenstein Monster?’ Research Evaluation, 20 (Sept. 2011), pp. 247-54; and other contributions in same issue.

3 S. Firestein, Failure: Why Science is So Successful (Oxford, 2015); [History of Science Congress Papers], Failed Innovations: Symposium (1992).

4 See P.C.W. Davies, About Time: Einstein’s Unfinished Revolution (New York, 1995); L.P. Williams (ed.), Relativity Theory: Its Origins and Impact on Modern Thought (Chichester, 1968); C. Christodoulides, The Special Theory of Relativity: Foundations, Theory, Verification, Applications (2016).

5 F. Finster and others (eds), Quantum Field Theory and Gravity: Conceptual and Mathematical Advances in the Search for a Unified Framework (Basel, 2012).

6 M.R. Schroeder, Number Theory in Science and Communications: With Applications in Cryptography, Physics, Biology, Digital Information and Computing (Berlin, 2008).

7 J. Mokyr, The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy (Princeton, 2002); A. Valero and J. van Reenen, ‘The Economic Impact of Universities: Evidence from Across the Globe’ (CEP Discussion Paper No. 1444, 2016), in Vox: https://voxeu.org/article/how-universities-boost-economic-growth

8 For the common attribution and its uncertainty, see [D. Hirshman], ‘Adventures in Fact-Checking: Einstein Quote Edition’, https://asociologist.com/2010/09/04/adventures-in-fact-checking-einstein-quote-edition/

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 105 please click here

Historians, who study the past, don’t undertake this exercise from some vantage point outside Time. They, like everyone else, live within an unfolding temporality. That’s very fundamental. Thus it’s axiomatic that historians, like their subjects of study, are all equally Time-bound.1

Historians, who study the past, don’t undertake this exercise from some vantage point outside Time. They, like everyone else, live within an unfolding temporality. That’s very fundamental. Thus it’s axiomatic that historians, like their subjects of study, are all equally Time-bound.1

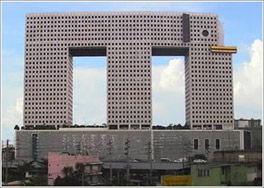

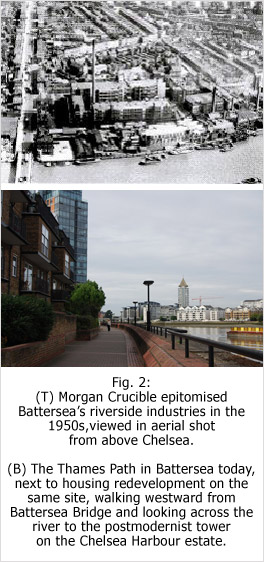

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital.

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital. But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality.

But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality. • A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

• A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed.

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed. So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece.

So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece. As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration.

As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration. Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

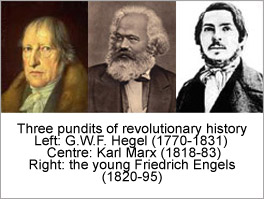

Secondly: political revolutions also need to be located within a spectrum of different sorts and degrees of change. It is very rarely, if ever, that everything is transformed all at once. The rhetoric of dramatic metamorphosis is both fearful and hopeful: ‘All changed, changed utterly;/ A terrible beauty is born’, as Yeats saluted the Irish Easter Rising in 1916. Yet, when the dust dies down, continuity turns out to have dragged at the heels of revolution after all. What is known as admirable heritage to its fans is deplorable inertia to its critics. Thus Karl Marx once denounced with righteous passion: ‘the tradition of all the dead generations [that] weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’.

Secondly: political revolutions also need to be located within a spectrum of different sorts and degrees of change. It is very rarely, if ever, that everything is transformed all at once. The rhetoric of dramatic metamorphosis is both fearful and hopeful: ‘All changed, changed utterly;/ A terrible beauty is born’, as Yeats saluted the Irish Easter Rising in 1916. Yet, when the dust dies down, continuity turns out to have dragged at the heels of revolution after all. What is known as admirable heritage to its fans is deplorable inertia to its critics. Thus Karl Marx once denounced with righteous passion: ‘the tradition of all the dead generations [that] weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’. Yet no. Not only does fundamental change frequently develop via evolutionary rather than revolutionary means; but revolutions do not always introduce macro-change. They can fail, abort, halt, recede, fudge, muddle, diverge, transmute and/or provoke counter-revolutions. The complex failures and mutations of the communist revolutions, which were directly inspired in the twentieth century by the historical philosophy of Marx and Engels, make that point historically, as well as theoretically.

Yet no. Not only does fundamental change frequently develop via evolutionary rather than revolutionary means; but revolutions do not always introduce macro-change. They can fail, abort, halt, recede, fudge, muddle, diverge, transmute and/or provoke counter-revolutions. The complex failures and mutations of the communist revolutions, which were directly inspired in the twentieth century by the historical philosophy of Marx and Engels, make that point historically, as well as theoretically.