If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2016)

After contributing to a panel discussion on 22 September 2016 at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London, I’ve expanded my notes as follows:

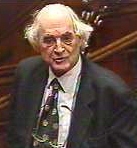

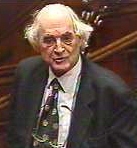

When remembering my colleague Conrad Russell (1937-2004),1 the first thing that comes to mind is his utterly distinctive presence. He was an English eccentric, in full and unselfconscious bloom. In person, Conrad was tall, latterly with something of a scholar’s stoop, and always with bright, sharp eyes. But the especially memorable thing about him was his low, grave voice (‘Conrad here’, he would intone, sepulchrally, on the phone) and his slow, very precise articulation. This stately diction, combining courtesy and erudition, gave him a tremendous impact, for those who could wait to hear him out.

He once told me that his speaking manner was something that he had consciously developed, following advice given to him in his youth by his father. In fact, given his life-long wish not to be overshadowed by his famous parent, Conrad spoke very rarely about the mathematician and public intellectual Bertrand Russell (1872-1970). Conrad, the only child of Russell’s third marriage, was brought up by his mother, who lived in isolation from the rest of the family. But the eminent father had once advised his young son to formulate each sentence fully in his mind, before giving voice to each thought.2 (Not an easy thing to do). The suggestion evidently appealed to something deep within Conrad, for he embraced the slow, stately style from his youth and maintained it throughout his lifetime.

One result was that a proportion of his students, initially at London University’s Bedford College (as it then was),3 were terrified by him, although another percentage found him brilliant and immensely stimulating. Only very few disliked him. Conrad was manifestly a kindly person. He didn’t seek to score points or consciously to attract attention as an eccentric. Yet his emphatic speaking style, laced with erudite references to English politics in the 1620s, and witticisms with punch-lines in Latin, could come as a shock to undergraduates. Especially as Conrad did not just speak ‘at’ people. He wanted replies to his questions, and hoped for laughter following his jests.

Because he thought carefully before speaking, he was also wont to preface his remarks with a little exclamation, ‘Em …’, to establish his intention of contributing to the conversation, always followed by a Pinteresque pause. That technique worked well enough in some contexts. However, when Conrad took up a prestigious academic post at Yale University (1979-84), a number of his American students protested that they could not understand him. And in a society with a cultural horror of silence, Conrad’s deliberative pauses were often filled by instant chatter from others, unintentionally ousting him from the discussion. A very English figure, he admitted ruefully that he was not psychologically at ease in the USA, much as he admired his colleagues and students at Yale. Hence his relief was no secret, when he returned to the University of London, holding successive chairs at University College London (1984-90) and King’s College (1990-2003). By this time, his lecturing powers were at their full height – lucid, precise, and argumentative, all at once.

And, of course, when in 1987 he inherited his peerage as 5th Earl Russell, following the death of his half-brother, Conrad found in the House of Lords his ideal audience. They absolutely loved him. He seemed to be a voice from a bygone era, adding gravitas to every debate in which he participated. Recently, I wondered how far Conrad was reproducing his father’s spoken style, as a scion of the intellectual aristocracy in the later nineteenth century. But a check via YouTube dispelled that thought.4 There were some similarities, in that both spoke clearly and with authority. Yet Bertrand Russell’s voice was more high-pitched and his style more insouciant than that of his youngest child.

The second unmistakable feature of Conrad’s personality and intellect was his literal-mindedness. He treated every passing comment with complete seriousness. As a result, he had no small talk. His lifeline to the social world was his wife Elizabeth (née Sanders), a former student and fellow historian whom he married in 1962. She shared Conrad’s intellectual interests but was also a fluent conversationalist. At parties, Elizabeth would appear in the heart of a crowd, wielding a cigarette and speaking vivaciously. Conrad meanwhile would stand close behind her, his head slightly inclined and nodding benignly. They were well matched, remaining devoted to one another.

|

Fig.1 Conrad and Elizabeth Russell on the stump for Labour in Paddington South (March 1966).

|

My own experience of Conrad’s literal-mindedness came from an occasion when we jointly interviewed a potential candidate for an undergraduate place in the History Department at Bedford College. (That was in the 1970s, before individual interviews were replaced by generic Open Days). A flustered candidate came in late, apologising that the trains were delayed. Within moments, Conrad was engaging her in an intense discussion about the running of a nationalised rail service (as British Rail then was) and the right amounts of subsidy that it should get as a proportion of GDP. The candidate gamely rallied, and did her best. But her stricken visage silently screamed: ‘all I did was mention that the train was late’.

After a while, I asked if she’d like to talk about the historical period that she was studying for A-level. Often, interview candidates became shifty at that point. On this occasion, however, my suggestion was eagerly accepted, and the candidate discoursed at some length about the financial problems of the late Tudor monarchy. Conrad was delighted with both elements of her performance; and, as we offered her a place, commented that the young were not as uninterested in complex matters of state as they were said to be. The candidate subsequently did very well – although, alas for symmetry, she did not go on to save British Rail – but I was amused at how her apparent expertise was sparked into life purely through the intensity of Conrad’s cross-questioning.

His own interest in such topical issues was part and parcel of his life-long political commitment. At that time, he was still a member of the Labour Party, having stood (unsuccessfully) as the Labour candidate for Paddington South in 1966. But Conrad was moving across the political spectrum during the 1970s. He eventually announced his shift of allegiance to the Liberals, characteristically by writing to The Times; and later, in the Lords, he took the Liberal Democrat whip. He wanted to record his change of heart, to avoid any ambiguity; and, as a Russell, he assumed that the world would want to know.

Conrad’s literalness and love of precision were qualities that made him a paradoxical historian when interrogating written documents. On the one hand, he brought a formidable focus upon the sources, shedding prior assumptions and remaining ready to challenge old interpretations. He recast seventeenth-century political and constitutional history, as one of the intellectual leaders of what became known as ‘revisionist’ history.5 He argued that there was no evidence for an inevitable clash between crown and parliament. The breakdown in their relationship, which split the MPs into divided camps, was an outcome of chance and contingency. Those were, for him, the ruling forces of history.

On the other hand, Conrad’s super-literalism led him sometimes to overlook complexities. He did not accept that people might not mean what they said – or that they might not say what they really meant at all. If the MPs declared: ‘We fear God and honour the king’, Conrad would conclude: ‘Well, there it is. They feared God and honoured the king’. Whereas one might reply, ‘Well, perhaps they were buttering up the monarch while trying to curtail his powers? And perhaps they thought it prudent not to mention that they were prepared, if need be, to fight him – especially if they thought that was God’s will’. There are often gaps within and between both words and deeds. And long-term trends are not always expressed in people’s daily language.

In case stressing his literalism and lack of small talk makes Conrad sound unduly solemn, it’s pleasant also to record a third great quality: his good humour. He was not the sort of person who had a repertoire of rollicking jokes. And his stately demeanour meant that he was not an easy man to tease. Yet, like many people who had lonely childhoods, he enjoyed the experience of being joshed by friends, chuckling agreeably when his leg was being pulled. Common jokes among the Bedford historians were directed at Conrad’s unconventional self-catered lunches (spicy sausages with jam?) or his habit of carrying everywhere a carafe of stale, green-tinged water (soluble algae, anyone?). He was delighted, even if sometimes rather bemused, by our ribbing.

Moreover, on one celebrated occasion, Conrad turned a jest against himself into a triumph. The Head of Bedford History, Professor Mike (F.M.L.) Thompson, was at some date in the mid-1970s required to appoint a Departmental Fire & Safety Officer. It marked the start of the contemporary world of regulations for everything. Mike Thompson, with his own quixotic humour, appointed Conrad Russell to the role, amidst much laughter. Not only was he the caricature of an untidy professor, living in a chaos of books and papers, but he was, like his wife Elizabeth, an inveterate chain-smoker. In fact, there were good reasons for taking proper precautions at St John’s Lodge, the handsome Regency villa where the History Department resided, since the building lacked alternative staircases for evacuation in case of emergency. Accordingly, a fire-sling was installed in Conrad’s study, high on the top floor. Then, some months later, he instituted a rare emergency drill. At the given moment, both staff and students left the building and rushed round to the back. There we witnessed Conrad, with some athleticism,6 leap into the fire-sling. He was then winched slowly to the ground, discoursing gravely, as he descended, on his favourite topic (parliamentary politics in the 1620s) – and smoking a cigarette.

|

Fig.2 Frontage of St John’s Lodge, the Regency villa in Regent’s Park,

where the Bedford College historians taught in the 1960s and 1970s.

Conrad Russell’s room was on the top floor, at the back.

|

Later, Conrad referred to his years in Bedford’s History Department with great affection. Our shared accommodation in St John’s Lodge, five minutes away from the rest of the College, created a special camaraderie. The 1970s in particular were an exciting and challenging period for him, when he was refining and changing not only his politics but also his interpretation of seventeenth-century history. The revisionists attracted much attention and controversy, especially among political historians. (Economic, demographic, social and urban historians tended to stick to their own separate agendas). Collectively, the revisionists rejected the stereotypes of both ‘Whig’7 and Marxist8 explanations of long-term change. Neither the ‘march of progress’ nor the inevitable class struggle would suffice to explain the intricacies of British history. But what was the alternative big picture? Chance and contingency played a significant role in the short-term twists and turns of events. Yet the outcomes did not just emerge completely at random. In the very long run, Parliament as an institution did become politically more powerful than the monarch, even though the powers of the crown did not disappear.

By the 1990s, the next generation of political historians were beginning to revise the revisionists in turn. There were also new challenges to the discipline as a whole from postmodernist theory. In private conversation, Conrad at times worried that the revisionists’ critique of their fellow historians might be taken (wrongly) as endorsing a sceptical view that history lacks any independent meaning or validity.

Meanwhile, new research fashions were also emerging. Political history was being eclipsed by an updated social history; gender history; ethnic history; cultural history; the history of sexuality; disability history; world history; and studies of the historical meanings of identity.

Within that changing context, Conrad began to give enhanced attention to his role in the Lords. His colleagues among the Liberal Democrats appreciated the lustre he brought to their cause. In 1999 he topped the poll by his fellow peers to remain in the House, when the number of hereditary peers was drastically cut by the process of constitutional reform. And, at his funeral, Conrad Russell was mourned, with sincere regret, as the ‘last of the Whigs’.

|

Fig.3 Conrad Russell, 5th Earl Russell, speaking in the House of Lords in the early twenty-first century.

|

There is, however, deep irony in that accolade. In political terms, it has some truth. He was proud to come from a long line of aristocrats, of impeccable social connections and Whig/Liberal views. Listening to Conrad, one could imagine hearing the voice of his great-grandfather, Lord John Russell (1792-1878), one of the Whig architects of the 1832 Reform Act. Moreover, this important strand of aristocratic liberalism was indeed coming to an end, both sociologically and politically. On the other hand, as already noted, Conrad the historian was a scourge of both Whigs and Marxists. Somehow his view of history as lacking grand trends (say, before 1689) was hard to tally with his belief in the unfolding of parliamentary liberalism thereafter.9 At very least, the interpretative differences were challenging.

Does the ultimate contrast between Conrad Russell’s Whig/Liberal politics and his polemical anti-Whig history mean that he was a deeply troubled person? Not at all. Conrad loved his life of scholarship and politics. And he loved following arguments through to their logical outcomes, even if they left him with paradoxes. Overall, he viewed his own trajectory as centrist: as a historian, opposing the Left in the 1970s when it got too radical for him, and, as a politician, opposing the Tories in the 1980s and 1990s, when they became dogmatic free-marketeers, challenging the very concept of ‘society’.

If there is such a thing as ‘nature’s lord’ to match with ‘nature’s gentleman’, then Conrad Russell was, unselfconsciously, one among their ranks. He was grand in manner yet simple in lifestyle and chivalric towards others. One of his most endearing traits was his capacity to find a ‘trace of alpha’ in even the most unpromising student. Equally, if there is such a thing as an intellectual’s intellectual, then Conrad Russell was another exemplar, although these days a chain-smoker would not be cast in the role. He was erudite and, for some critics, too much a precisian, preoccupied with minutiae. Yet he was demonstrably ready to take on big issues.

Putting all these qualities together gives us Conrad Russell, the historian and politician who was often controversial, especially in the former role, but always sincere, always intent. One of his favourite phrases, when confronted with a new fact or idea, was: ‘It gives one furiously to think’.10 And that’s what he, courteously but firmly, always did.

1 Conrad Sebastian Robert Russell (1937-2004), 5th Earl Russell (1987-2004), married Elizabeth Sanders (d.2003) in 1962. Their sons, Nicholas Lyulph (d.2014) and John Francis, have in turn inherited the Russell earldom but, post Britain’s 1999 constitutional reforms, not a seat in the House of Lords.

2 Conrad volunteered this information, in the context of a discussion between the two of us, in the early 1970s, on the subject of parental influence upon their offspring.

3 Merged in 1985 to become part of Royal Holloway & Bedford New College, these days known simply as Royal Holloway, University of London (RHUL), located at Egham, Surrey.

4 Compare the BBC Interview Face-to-Face with Bertrand Russell (1959; reissued 2012), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bZv3pSaLtY with Conrad Russell’s contribution to The Lords’ Tale, Part 18 (2009), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJ_u1WM7CYA.

5 The intellectual excitement of that era, among revisionist circles, was well conveyed by fellow-panellist, Linda Levy Peck (George Washington University, Washington, DC).

6 Talking of Conrad Russell’s athleticism, some of his former students drew attention to his love of cricket. He could not only carry his bat but he also bowled parabolic googlies which rose high into the sky, spinning wildly, before dropping down vertically onto the wicket behind the flailing batsman, often taking the wicket through sheer surprise.

7 The term ‘Whig’, first coined in 1678/9, referred to a political stance which had considerable but never universal support throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in support of parliamentary constraints upon the unfettered powers of monarchy, a degree of religious toleration, moderate social and political reforms, and opposition to the more pro-monarchical Tories. The ‘Whig interpretation of history’, which again was never universally supported, tended to view the unfolding of British history as the gradual and inexorable march of liberal constitutionalism, toleration, technological innovation, and socio-political reforms, together termed ‘progress’.

8 On which, see S. Rigby, Marxism and History: A Critical Introduction (Manchester, 1987, 1998).

9 This point was perceptively developed by fellow-panellist, Nicholas Tyacke (University College London).

10 Conrad showed no sign of being aware (and probably would have laughed to discover) that this phrase originated with Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot, in Lord Edgware Dies (1933), ch.6.

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 72 please click here

Collectively, the 15th International Congress on the Enlightenment (ICE), focusing upon Enlightenment Identities, was a huge triumph. For five days in Edinburgh in July 2019 some 2000 international participants rushed from event to event. There were not only 477 learned panel presentations and five great plenaries but also sundry conducted walks, coach tours to special venues, a grand reception, a superb concert, a pub quiz, and an evening of energetic Highland dancing. So much was happening that heads spun, and not just from the jovial Edinburgh hospitality.

Collectively, the 15th International Congress on the Enlightenment (ICE), focusing upon Enlightenment Identities, was a huge triumph. For five days in Edinburgh in July 2019 some 2000 international participants rushed from event to event. There were not only 477 learned panel presentations and five great plenaries but also sundry conducted walks, coach tours to special venues, a grand reception, a superb concert, a pub quiz, and an evening of energetic Highland dancing. So much was happening that heads spun, and not just from the jovial Edinburgh hospitality.

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide.

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide. On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’.

On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’.