If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2023)

[Also PJC/website/Pdf70]

Image 1: The Vote of a Poor Man Equalled

the Vote of an Aristocrat’s Younger Son or that of a Wealthy Merchant

Hogarth’s 1755 image of a wounded and impoverished old soldier,

reaching the head of the queue to cast his vote (in the days of open polling),

was intended satirically.

But it demonstrates that some eighteenth-century voters in Britain were

men from well outside the social elite –

a factor of long-term significance in Britain’s long march towards democracy.

Detail from William Hogarth’s The Humours of an Election, III:

The Polling (1758 engraving of 1755 oil-painting) |

Note: This essay appears as a feature ‘Towards Democracy’

in the Newcastle University website for the Project on

Eighteenth-Century Political Participation & Electoral Culture:

see https://ecppec.ncl.ac.uk/features/

Democracy is not a flawless form of government. Nor do all democracies survive for all time. Nonetheless, representative democracies uphold the ideal notion of a rational politics, in which all citizens have an equal vote – all exercise their judgment in choosing representatives, who in turn vote to run the country on behalf of their fellow citizens – and all calmly accept the outcome of a majority vote.1

Such a system was a complete anathema to eighteenth-century believers in absolute monarchy. ‘Democracy’ would equate to rule by the unlettered, irrational, property-less masses. And the result would simply be chaos. Rule by one individual, considered to be divinely instituted, was the countervailing opposite, promoting order, balance, and due protection for property rights.

Transitions from autocracy to democracy have, historically, been very variegated. There are known examples of great revolutions (as in France in 1789), which sought democracy but ended in dictatorship, at least in the short term. And there have been plenty of uprisings in the name of democracy which have briefly flourished but as quickly failed.2

The British case was different. Its progression to democracy was a classic example of slow evolutionary change. Just as successive British monarchs have, after the 1649 execution of Charles I on a charge of High Treason, lost formal governing powers and transitioned into ceremonial figureheads,3 so a countervailing slow trend was leading towards increased popular participation in government, eventually leading to democracy. Changes did not come at a steady pace; but in fits and starts. But, over the long term, they did come – and did so without anything as drastic as a full-scale popular revolution.

There was no gradualist master-plan. But, de facto, Britain took a stepped approach to democracy. In the nineteenth century, the franchise was extended in stages to all adult males (1832; 1867; 1884); while in the later nineteenth century, female rate-payers were allowed to vote in municipal elections after legislation in 1869, before adult women, both rich and poor, gained the parliamentary franchise in two stages in the twentieth century (1918; 1928).4

One key factor that helped to prepare the terrain for democracy was Britain’s eighteenth-century experience of orderly voting in public elections, undertaken by large numbers of adult male voters. It amounted to a constitutionalist tradition which was pre-democratic but which, at the same time, inculcated some core principles later incorporated into democratic politics.

Certainly, there are numerous caveats to be made. The eighteenth-century electoral franchise was not systematic. It varied between the counties and the parliamentary boroughs; and between one of those boroughs and another.5

Furthermore, far from all Britain’s expanding towns had the right to return MPs to Parliament, while – before parliamentary reform in 1832 – some tiny places did. By that date, it had become a glaring anomaly that great centres like Manchester and Birmingham had no direct parliamentary representation. Yet, before 1832, seven Wiltshire electors in the decayed settlement of Old Sarum voted to elect two MPs. In practice, most of the so-called ‘pocket boroughs’ were controlled by the local great landowner, who chose a candidate and bribed or ‘treated’ the electors to get their support. Reformers were scathing. And they renamed these seats as ‘rotten boroughs’ – a hostile term that stuck.6

Nonetheless, throughout the eighteenth century, a number of big cities – notably London, Westminster, Norwich, Bristol, and Newcastle upon Tyne – did have very sizeable electorates. They were far too numerous and sturdily independent to be controlled by rich noble patrons.

And as these thousands of electors voted regularly, they gained electoral experience and proved – to themselves and to the wider world – that men of ‘lower’ status and wealth could participate responsibly in political life. What’s more, in some places (though again, not in all) elections were also held to fill municipal and parochial posts, such as those of beadles, constables, inquest-men and scavengers.

As a result, electors in the open constituencies had the regular experience of deciding to vote – or not to vote – and, if voting, then deciding for whom to vote. For instance, in the London metropolitan region with its many parliamentary constituencies, it is estimated that, between 1700 and 1850, about one third of a million men went to the polls on different occasions, casting between them, including multiple votes in multi-member seats, more than one million votes.7 To repeat: some electors abstained. Others voted rarely; or without deep thought (as can happen today). Yet all lived in a civic culture of regular elections and political debate, where many manifestly did care – and voted to prove it.

Viewed over the long term, eighteenth-century Britain’s lively electoral experiences had three big consequences. Firstly, they established the principle and practice that, among the enfranchised electorate, all voters are equal at the polls. They could and did try to influence one another before any votes were cast. Wealthy men might pay for political leaflets or ‘treat’ voters in the local hostelries. Poor men might demonstrate aggressively; or organise to maximise their support. All these things happened. Yet, at the polls, each vote counted the same. And the victory went to the majority.

Consequently, voting in the large constituencies was a shared experience across the social classes. Queues at polls included politicians and aristocrats (other than titled heads of noble families, who sat in the House of Lords); bankers and plutocrats; professional men and publicans; builders and brokers; plus multitudes of shopkeepers and artisans; and a not insignificant number of labourers, porters, and servants.8 Such cheek-by-jowl voting did not in itself uproot the underlying socio-economic distribution of power and wealth. Yet it marked an egalitarian principle. When polling, all electors are equal: an instructive lesson, in a profoundly unequal society, for all to imbibe.

Secondly, the eighteenth-century’s many elections encouraged the flowering of public political campaigning. Of course, a lot of politicking continued privately, behind the scenes. And publicly, as already noted, it might happen that political calm prevailed in the ‘pocket’ boroughs, whilst ‘election fever’ was rampaging elsewhere. Nonetheless, in a period when literacy levels were steadily rising – and the output of the press, including satirical squibs as well as serious tracts, was richly diversifying – political awareness was spreading, not only among the electors but also across the wider society.

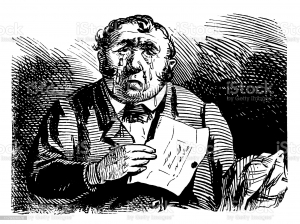

Image 2: The Excitement of Public Political Campaigns

Detail from Robert Dighton’s depiction of Londoners at the pollsin the Westminster constituency (1788):showing a lively cross-class crowd of electors and onlookers,including an elegant young upper-class gentleman (R)and a plain but not poor citizen (Centre) who is being deftly pick-pocketed –

plus others carrying banners, a woman selling election literature, and a crying child.

Not all were thinking deeply about how to cast their votes

but the hubbub spread the public awareness that ‘the people’ had an electoral role to play. indication of popular participation in politics |

This era accordingly saw the advent of systematic electoral campaigning; with organised nation-wide parties (subject to change and flux, as happens today), with rival political slogans and manifestoes; with rival speeches at the hustings; with support from rival newspapers; with teams of canvassers; with ward organisers; with celebrity endorsements; with election songs; down to the details of rival party colours, sported not only by candidates and canvassers but also by the partisan crowds who gathered to witness the excitements during close contests. Elections thus triggered wider political debates and a sense of civic awareness. The fun of mock elections in part parodied these processes, whilst simultaneously testifying to a popular awareness of their role.

A third consequence, finally, was to establish the expectation that political disputes be settled by constitutional means, rather than by fighting. True, there were many riots and some rebellions in eighteenth-century Britain.9 Yet a counter-vailing constitutionalist tradition was becoming strongly entrenched. Parliament in this era was establishing its core rules and procedures; and its institutional prestige was rising. Equally, too, the electoral system, which voted MPs into office, was gaining in status. Thus election results, after contests in many big constituencies, were often taken to represent ‘public opinion’.10

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that elections were not organised from the centre, by royal courtiers or ministers; but locally, by county and municipal officials. They called the contests; and acted as returning officers. And, if the outcome of a parliamentary election was disputed, the case was referred for adjudication not to royal officials but to Parliament. Voters were thus outriders for the prestige of the legislative body. Hence the growing number of reformers, who, from the 1770s onwards, campaigned to widen the franchise, did so not to undercut the powers of Parliament but to improve them – by improving its electoral base.

In effect, therefore, political reformers from the 1770s onwards were trying to redirect an existing constitutionalist tradition into a democratic direction. And they cited the eighteenth-century’s experience to reassure the doubters. It was true that popular passions at times overran good order. There were numerous election affrays; and a few significant election riots. Yet those were very much the exception. Many elections were quiet and routine – and some were not contested at all, producing a result without any political heat or disputation.

Indeed, that routine functioning marked instead the triumph of constitutionalism. It could encompass concord and it certainly did not depend upon violence and bloodshed. Instead, political reformers stressed that those outside the political elite were capable of taking a sustained and constructive political role. Thus the Whig peer (and historian) Lord Macaulay in December 1831 supported reform, in a famous set of speeches, by stressing the responsible behaviour of the London electors. No extremists there. Instead, the London seats had over many years become ‘famed for the meritorious quality of their MPs and their constituents’ readiness to support that merit’.11

Image 3: A Serious Politician Sustained by his Westminster Electorate

Charles James Fox (1749-1806) was the controversial Whig reformer who made his name as unofficial Leader of the Opposition to the conservative-minded government of William Pitt.

Fox is satirised here as an overweight, unkempt Demosthenes (the classical Greek orator)

but the image also caught the power of Fox’s oratory as a ‘man of the people’

which won him vital constitutional support from the Westminster electorate. |

Full democracy was not a mainstream possibility in eighteenth-century Britain. The national political tradition was one of oligarchic constitutionalism, with before 1832 a highly unsystematic constitution to boot.

Yet, within that lack of system, there was scope for significant new developments. The rules and practices of routine electoral politics were being collectively constructed. Elections were becoming normalised. And the power to vote was accepted as a ‘right’ of every qualified elector. In fact, in the large open constituencies, many comparatively poor electors would not have qualified for the vote under the new middle-class rate-paying franchise introduced in 1832. But, significantly, the reform legislation did not disenfranchise any of those existing electors. They kept their ‘right’ to vote throughout their lifetimes.

Determined political reformers, moreover, wanted more participation, not less. They proposed to extend the franchise to all adult males. A few visionaries talked also of votes for women.

Pathways of historical change were often long and winding. And they are rarely pre-destined. Nonetheless, the electors in eighteenth-century Britain were the historic precursors of Britain’s democratic electors in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. There was a voting tradition long before there was full democracy. These eighteenth-century electors also influenced Britain’s North American colonists, who framed the constitution of the new USA post-1783.12 The republican system was built upon regular elections plus an extensive adult male franchise (to which, later, adult male ex-slaves and, later still, all adult women were added – albeit not without epic struggles).

Britain’s eighteenth-century electoral culture was thus mightily influential. It was imperfect and unsystematic. Yet, in practice, it established: the equality of votes; the arts of public campaigning; and the seriousness of electoral politics. It was a vital history, not of democracy; but of proto-democracy.

ENDNOTES:

1 B. Crick, Democracy: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2002); J-W. Müller, Democracy Rules (2021).

2 Among a huge literature, see C. Welzel, ‘Theories of Democratization’, in C.W. Haerpfer and others (eds), Democratization (Oxford, 2009; 2019), pp. 74-91; and M.K. Miller, Shocks to the System: Coups, Elections and War on the Road to Democratization (Princeton, NJ, 2021).

3 B. Hubbard, The Changing Power of the British Monarchy (Oxford, 2018); F. Prochaska, Royal Bounty: The Making of a Welfare Monarchy (New Haven, 1995).

4 For context, see M.N. Duffy, The Emancipation of Women (Oxford, 1967).

5 See F. O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons and Parties: The Unreformed Electoral System of Hanoverian England, 1734-1832 (Oxford, 1989).

6 R. Mason, The Struggle for Democracy: Parliamentary Reform, from the Rotten Boroughs to Today (Stroud, 2015).

7 Documented by Edmund M. Green, Penelope J. Corfield and Charles Harvey, Elections in Metropolitan London, 1700-1850: Vol. 1 Arguments and Evidence; Vol. 2, Metropolitan Polls (Bristol, 2013); and evidence within the London Metropolitan Database.

8 All these occupations, plus many more, appear in the London Metropolitan Database.

9 See e.g. I. Gilmour, Riot, Risings and Revolution: Governance and Violence in Eighteenth-Century England (1992).

10 See summary in P.J. Corfield, The Georgians: The Deeds and Misdeeds of Eighteenth-Century Britain (London, 2022), pp. 180-85.

11 T.B. Macaulay, Speeches of Lord Macaulay, Corrected by Himself (1886), p. 34.

12 See variously R.R. Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (New York, 2009); M. Lienesch, New Order of the Ages: Time, the Constitution, and the Making of Modern American Political Thought (Princeton, NJ., 1988; 2016); and ‘A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns, 1788-1825’: https://elections.lib.tufts.edu.

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 146 please click here