MONTHLY BLOG 157, HOW THE GEORGIANS CELEBRATED MIDWINTER (*)

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2024)

Variety was the spice of Midwinter festivities under the Georgians. There was no cultural pressure to conform to one standard format. Instead, people responded to diverse regional, religious and family traditions. And they added their own preferences too. Festivities thus ranged from drunken revelries to sober Puritan spiritual meditation, with all options in between.

It was the Victorians from the 1840s onwards – with the potent aid of Charles Dickens – who standardised Christmas as a midwinter family festivity. They featured Christmas trees, puddings, cards, presents, carol services, and ‘Father Christmas’. It’s a tradition that continues today, with some later additions. Thus, on Christmas Days in Britain since 1932, successive monarchs have recorded their seasonal greetings to the nation, by radio (and later TV).

Georgian variety, meanwhile, was produced by a continuance of older traditions, alongside the advent of new ones. Gift-giving at Christmas had the Biblical sanction of the Three Wise Men, bringing to Bethlehem gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. So the Georgians substituted their own luxury items. An appreciated gift, among the wealthy, was a present of fine quality gloves. But, interestingly, that custom, which was well established by 1700, was already on the wane by 1800 as fashions in clothing changed. Embroidered gloves, made of lambskin, doeskin, or silk, were given to both men and women, as Christmas or New Year gifts. These luxury items may be said therefore to have symbolised the hand of friendship.

|

Fig.1: Add MS 78429, John Evelyn’s Doe-Skin Gloves, |

The first illustration shows a fringed and embroidered glove once owned by the diarist John Evelyn. It was presented to him by the young Russian Tsar, Peter the Great. He had, during his semi-clandestine stay in England in 1698, resided in a property at Deptford, owned by Evelyn. The headstrong visitor caused considerable damage. So Peter’s farewell gift to Evelyn might be seen not so much as a mark of friendship but as something of a royal brush-off.

Presents can, after all, convey many messages. In the Georgian era, it was customary also for clients or junior officials to present gloves as Christmas or New Year gifts to their patrons or employers. The offering could be interpreted as thanks for past services rendered – or even as a bribe for future favours. That was especially the case if the gloves contained money, known in the early eighteenth century as ‘glove money’.

For example, the diarist Samuel Pepys, who worked for the Admiralty Board, had a pleasant surprise in 1664. A friendly contractor presented Pepys’ wife with gloves, which were found to contain within them forty pieces of gold. Pepys was overjoyed. (Today, by contrast, strict policies rightly regulate the reception of gifts or hospitality by civil servants and by MPs).

Meanwhile, individuals among the middling and lower classes in Georgian Britain did not usually give one another elaborate presents at Christmas. Not only did they lack funds, but the range of commercially available gifts and knick-knacks was then much smaller.

Instead, however, there was a flow of charitable giving from the wealthy to the ‘lower orders’. Churches made special Christmas collections for poor families. Many well-to-do heads of household gave financial gifts to their servants; as did employers to their workers. In order to add some grace to the transaction, such gifts of money were presented in boxes. Hence the Georgians named the day-after-Christmas as ‘Boxing Day’ (later decreed as a statutory holiday in 1871). Such activities provide a reminder that midwinter was – then as today – a prime time for thanking workers for past services rendered – as well as for general charitable giving.

Innovations were blended into older Midwinter traditions. Houses interiors in 1700 might well be festooned with old-style holly and ivy. By 1800, such decorations were still enjoyed. But, alongside, a new fashion was emerging. It was borrowed from German and Central European customs; and the best-known pioneer in Britain was George III’s Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. In 1800, she placed a small yew tree indoors and hung it with decorations. Later, a small fir was substituted, becoming the Victorians’ standard ‘Christmas Tree’, as it remains today.

Overlapping customs were, however, feted in the cheery Christmas carol, ‘Deck the Hall(s) with Boughs of Holly’. It was an ancient Welsh ballad, Nos Galan, habitually sung on New Year’s Day. Child singers were then treated by gifts of skewered apples, stuck with raisins. ‘Deck the Hall(s)’ was later given English lyrics in 1862 by a Scottish bard. And it’s still heartily sung – long after holly has lost its decorative primacy.

Many famous Christian hymns were also newly written in the Georgian era. They included: While Shepherds Watched … (1703); Hark! The Herald Angels Sing! (1739); and Adeste Fideles/ O Come All Ye Faithful (Latin verses 1751; English lyrics 1841). These all appeared in the 1833 publication of Christmas Carols, Ancient & Modern, edited by the antiquarian William Sandys/ He had recovered many of these songs from the oral tradition. Now they were all recorded in print for future generations.

Notably, a number of the so-called Christmas carols were entirely secular in their message. Deck the Hall(s) with Boughs of Holly explained gleefully: ’Tis the season to be jolly/ Fa la la la la la la la la. No mention of Christ.

Similarly, the carol entitled The Twelve Days of Christmas (first published in London in 1780) records cumulative gifts from ‘my true love’ for the twelve-day festive period. They include ‘five gold rings; … two turtle doves’ and a ‘partridge in a pear tree’. None are obviously Christian icons.

| Fig.2: Anonymous (1780). Mirth without Mischief. London: Printed by J. Davenport, George’s Court, for C. Sheppard, no. 8, Aylesbury Street, Clerkenwell. pp. 5–16 |

And as for Santa Claus (first mentioned in English in the New York press, 1773), he was a secularised Northern European variant of Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of 26 December. But he had shed any spiritual role. Instead, he had become a plump ‘Father Christmas’, laughing merrily Ho! Ho! Ho! (Songs about his reindeers followed in the twentieth century).

Given this utterly eclectic mix of influences, it was not surprising that more than a few upright Christians were shocked by the secular and bacchanalian aspects of these midwinter festivities. Puritans in particular had long sought to purify Christianity from what they saw as ‘Popish’ customs. And at Christmas, they battled also against excesses of drinking and debauchery, which seemed pagan and un-Christian. One example was the rural custom of ‘wassailing’. On twelfth night, communities marched to orchards, banging pots and pans to make a hullabaloo. They then drank together from a common ‘wassail’ cup. The ritual, which did have pagan roots, was intended to encourage the spirits to ensure a good harvest in the coming year. Whether the magic worked or not, much merriment ensued.

| Fig.3: A Fine and Rare 17th Century Charles II Lignum Vitae Wassail Bowl, Museum Grade – Height: 21.5 cm (8.47 in) Diameter: 25 cm (9.85 in). Sold by Alexander George, Antique Furniture Dealer, Faringdon, Oxfordshire: https://alexandergeorgeantiques.com/17th-century-charles-ii-lignum-vitae-wassail-bowl-museum-grade/ |

For their opposition to such frolics, the Puritans were often labelled as ‘Kill-Joys’. But they strove sincerely to live sober, godly and upright lives. Moreover, there was no Biblical authority for licentious Christmas revelries. Such excesses were ‘an offence to others’ and, especially, a ‘great dishonour of God’. So declared a 1659 law in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, specifying penalties for engaging in such ‘superstitious’ festivities.

Zealous opposition to riotous Christmases was especially found among Nonconformist congregations such as the Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists and Quakers. They treated 25 December, if it fell upon a weekday, just like any other day. People went soberly about their business. They fasted rather than feasted. Sober Christmases thus became customary in Presbyterian Scotland and in the Puritan colonies of New England. It was true that, over time, the strictest rules were relaxed. The Massachusetts ban was repealed in 1681 by a Royalist Governor of the colony. But ardent Puritans long distrusted all forms of ‘pagan’ Christmas excess.

One consequence was that people sought other outlets for midwinter revelry. A great example is Scotland’s joyous celebration of New Year’s Eve or Hogmanay. (The name’s origin is obscure). One ancient custom, known as ‘first footing’, declares that the first stranger to enter a house after midnight (or in the daytime on New Year’s Day) will be a harbinger of good or bad luck for the following year. An ideal guest would be a ‘tall dark stranger’, bearing a small symbolic gift for the household – such as salt, food, a lump of coal, or whisky. General festivities then ensue.

All these options allowed people to enjoy the ‘festive season’, whether for religious dedication – or to celebrate communally the midwinter and the hope of spring to come – or for a mixture of many motives.

No doubt, some Georgians then disliked the fuss. (Just as today, a persistent minority records a positive ‘hatred’ of Christmas). All these critics could share the words of Ebenezer Scrooge – the miser memorably evoked by Dickens in A Christmas Carol (1843). Scrooge’s verdict was: ‘Bah! Humbug!’

Yet many more give the salute: ‘Merry Christmas!’ Or on New Year’s Eve (but not before) ‘Happy Hogmanay!’ And, as for Scrooge: at the novel’s finale, he mellows and finally learns to love all his fellow humans. Ho! Ho! Ho!

ENDNOTES:

(*) First published in Yale University Press BLOG, December 2023: https://yalebooksblog.co.uk/2023/12/08/how-the-georgians-celebrated-christmas-by-penelope-j-corfield/

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 157 please click here

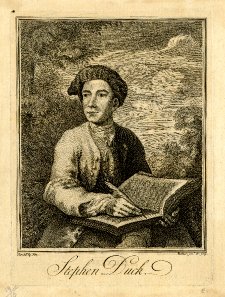

This BLOG resumes the theme of links between the Georgian era and the present.1 To do that, it takes one remarkable case-history, that of the Wiltshire poet, Stephen Duck (c.1705-56). [Yes, that was his real name] He was the son of an impoverished agricultural labourer. It’s likely that both his parents were illiterate. Yet Stephen Duck not only grew to gain poetic fame during his relatively short life but has been honoured ever since by an annual Duck Feast, held in his home village of Charlton, near Pewsey in Wiltshire.2

This BLOG resumes the theme of links between the Georgian era and the present.1 To do that, it takes one remarkable case-history, that of the Wiltshire poet, Stephen Duck (c.1705-56). [Yes, that was his real name] He was the son of an impoverished agricultural labourer. It’s likely that both his parents were illiterate. Yet Stephen Duck not only grew to gain poetic fame during his relatively short life but has been honoured ever since by an annual Duck Feast, held in his home village of Charlton, near Pewsey in Wiltshire.2