MONTHLY BLOG 163, DO PARTISAN IDENTITIES ADD A PLEASANT FLAVOUR TO DAILY LIVING – OR DO THEY REALLY CONSTITUTE A TRAP THAT UNDERMINES TRUE HUMAN SOLIDARITY?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2024)

| Fig.1: Shutterstock (2024) – Tug of War |

This BLOG is copy of my review, published in The Political Quarterly, Vol. 95/2 (April-June 2024), pp. 376-77, under the title ‘Uniting the Human Race’.

The book under review = Yascha Mounk, The Identity Trap:A Story of Ideas and Power in Our Time (Allen Lane, London, 2023), pp. 401. See link = http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13393.

Note: I was invited by the journal to contribute this review, since I have already written on the subject of ‘Identities’ in one of my most widely read and quoted BLOGs to date.1

The truth is that all individuals have more than one identity. They can be classified under many headings – whether by age, citizenship, class, education, ethnicity, gender, intelligence, language, region, religion, or sexuality … to name some commonly invoked criteria. If an identity is chosen voluntarily – for example as fan of a football club or pop group – it can be a delightful thing to own and to share with fellow fans. How much importance to attach to this identity then becomes a matter of choice.

Yet, if one special aspect of an individual’s existence is singled out and harshly attacked, then that one identity can quickly become all-preoccupying – whether in defiant pride or fearful resentment. Subjective emotions quickly overtake dispassionate analysis. Little wonder that political campaigners often appeal to simplified sectoral identities – and stoke the stereotypes, to keep the polemical fires burning. Human solidarity is undermined.

That danger is the core message of Yascha Mounk’s new book on The Identity Trap. He himself is of Polish parentage, born and reared in Germany, educated in Britain and the USA, and currently working in the USA. As a result, he lives with the complexities of identity. He has described himself, for example, as a native German-speaker who never felt at home in Germany. And in this book, he takes up his pen to warn the world against crude over-simplifications.

Mounk’s writing style is chatty and accessible. Each chapter ends with a useful list of key points. At the same time, his arguments are buttressed by ample documentation. His purpose is deadly serious.

An opening peroration explains both ‘the lure and the trap’ of identity politics (pp.1-21). The story gathers force by examining the American Civil Rights movement of the1960s. Insofar as the book has a (muted) hero, he is the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Junior. He sought to forge an ecumenical campaign, endorsed by people of all skin colours and backgrounds. In his famous speech ‘I have a Dream’ (August 1963), he expressed the hope that one day: ‘little black boys and girls will be holding hands with little white boys and girls’. A colour-blind universalism and egalitarianism will prevail.

However, some colleagues began to fear that King’s soaring idealism lacked hard-edged realism. They called instead for ‘Black Power’ to deliver a more immediate route to remedy injustices. And, over time, as progressive reforms came only slowly, others on the American political Left began to lose faith in universalist solutions to deep-rooted inequalities.

Accordingly, Part 1 of this book (pp. 23-81) examines the genesis of what Mounk calls the ‘identity synthesis’, whereby universalist/liberal values are exchanged for sectional ‘affinities’. After the Second World War – with the growing awareness of the Holocaust and the advent of the atomic bomb – faith in grand visions of the progressive unfolding of history began to falter. Thinkers like Michel Foucault (1926-84) argued that knowledge systems were nothing more (or less) than expressions of power. And Jean-François Lyotard (1924-98) proclaimed, equally firmly, that the era of ‘Modernity’ had ended. Instead, people were living in a new ‘Age of Postmodernity’, in which absolute values were yielding to relative ones.

Critics of universalism thus argued that legal systems were not benevolently impartial. They were instead ‘cloaks for privilege’. One radical maxim stated that ‘Neutrality is political’. Another declared that: ‘Racism is permanent’. Action to help society’s most disadvantaged groups (especially those defined by race, gender and sexuality) was urgently needed. Separate ‘identities’ were thus not to be denied. Instead, they were to be embraced – and each group should be helped separately, secure in the validity of its own ‘lived experience’. A ‘proud pessimism’ (pp. 69-71) had arrived.

After that, Mounk devotes Part 2 (pp. 83-126) to demonstrating how the ‘identity synthesis has swept through American Universities – and begun to influence corporate, philanthropic, and political life as well. The impact of social media simultaneously encourages the sharing of confessional narratives. In addition, Mounk notes the human capacity for ‘group think’, especially on emotive issues. Furthermore, the Presidency of Donald Trump fuelled a surge of frustration and anger amongst the American political Left. Radical zeal was channelled into immediate campaigns on the ‘identity’ frontier, where local successes could raise morale.

Having recognised the ‘lure’ of identity politics, Mounk turns in Part 3 (pp. 129-235) to refute its claims. Here he pulls no punches. The ‘identity synthesis’ has too many internal contradictions to constitute a coherent philosophy. For a start, disadvantaged people do not always agree among themselves. Then societies are not all perennially divided into mutually uncomprehending groups. There is much overlapping and sharing. Thus it is historically erroneous to think that each type of cultural output belongs exclusively to one specific group and cannot be adopted or adapted by others. Moreover, a ‘cancel’ culture that halts free discussion of such issues risks fuelling despotism rather righting injustices.

Building upon those criticisms, Mounk in Part 4 (pp. 239-90) ends with a rousing defence of liberal democratic values. With care and empathy, people can understand and help one another. Universalist programmes to provide good health care, housing, education, job opportunities, access to transport, peaceful neighbourhoods, and freedom from discrimination, can – given time and commitment – work wonders. ‘Progressive separatism’ is not actually progressive. Instead, it inculcates a negative pessimism.

These debates are likely to continue. But Mounk now detects a growing readiness among critics of the ‘identity synthesis’ to voice their objections – as he has decided to do in this admirably thoughtful book.

In that spirit, this reviewer wishes to add one further point that is not fully covered by Mounk. At one stage (p.100), he cites (disapprovingly) the case of an eminent American University where students are discouraged from stating that: ‘There is only one race, the human race’. Elsewhere, too, Mounk refers to racial classifications as ‘dubious’ (p. 262).

But let’s be franker. The attempt at establishing a so-called ‘scientific racism’ led into an intellectual blind alley. Experts could not even agree on the number of separate ‘races’. Today, geneticists confirm that all people carry variants of one biological template, known as the human genome.2 Hence individuals from all branches of the human family can inter-marry and breed fertile offspring – the fundamental test of one common species. Mounk does himself refer to the ever-growing number of so-called ‘mixed-race’ individuals (p.14), who do not fit into simple ‘racial’ classifications. But are they fully human? Of course, they are.

True, some people today maintain strongly racist attitudes. That’s an urgent problem for societies to address. Yet it’s not a good reason for endorsing the separatists. Humanity must avoid the ‘identity trap’ and walk with Martin Luther King. He sought to transform: ‘the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood’ [or: siblinghood!] King was brutally cut down in his prime. But his cause and his optimism are needed today more than ever. Can the human family get its global act together, at this time of climate crisis? That’s another huge and urgently-unfolding story … but anyone immediately seeking a measured faith in liberal human universalism should read Yascha Mounk.

ENDNOTES:

1 PJC, ‘Being Assessed as a Whole Person: A Critique of Identity Politics’, BLOG no.121 (Jan. 2021).

2 See esp. L. Cavalli-Sforza and F. Cavalli-Sforza, The Great Human Diasporas: The History of Diversity and Evolution (London, 1996).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 163 please click here

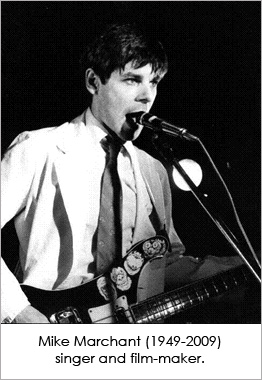

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide.

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide. On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’.

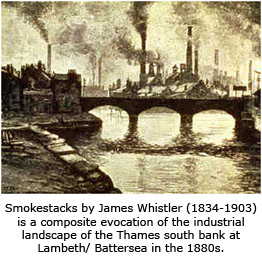

On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’. But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort.

But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort. The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends).

The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends). Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =

Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =