MONTHLY BLOG 162, HAPPY CANVASSING MEMORIES

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2024)

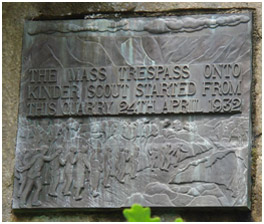

| Fig.1: Satire of Charles James Fox (kneeling centre), canvassing the Westminster parliamentary electors in 1784: detail from an anonymous print, entitled ‘A New Way to Secure a Majority: Or, No Dirty Work Comes Amiss’ (1784). Original in British Museum Dept. of Prints & Drawings, no: 1868,0808.5288. |

Happy canvassing memories indeed! I no longer go out knocking on doorsteps – been there, done that, for many years, from the age of fifteen onwards! But, in this month of busy electioneering, when many of my friends are still on the stump, I can’t keep the memories at bay …

Political activists have a very mixed reputation, as has the political process itself.1 Door-to-door canvassers are sometimes seen as pests. Or as cravenly kow-towing to the voters. The image of Charles James Fox, the Whig reform candidate in Westminster election in 1784 (shown in Fig.1) pulls absolutely no punches. He is shown as literally arse-licking the voters. The shopkeepers and tradesmen, meanwhile, are lining up to receive his grovelling submission. (Either way, it worked. Fox won the seat, despite intense campaigning against him from the government, headed by Fox’s great political rival, the Younger Pitt).2

Well, needless to say, the canvassing that I have undertaken was always more dignified. Generally, I enjoyed the process. Rarely encountered voters who were rude or personally unpleasant. Often, it was just a case of ‘Will you be voting Labour?’ …, and, after the reply: ‘Oh thank you’ … or not as the case may have been.

Meanwhile, there were, from time to time, real doorstep debates. We canvassers are not supposed to linger but instead are required to press on relentlessly. But I enjoyed the rare chances for real conversations. Once as a student, when canvassing close to my parental home in Sidcup, I remember an impromptu doorstep encounter – discussing the pros and cons of comprehensive education with a genuinely questing voter, who was keen to get my views – and to share his. It was a stimulating exchange.

Later, on another occasion, in 2004, after the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003, a voter said curtly to me, on the doorstep, that all supporters of the Labour Party were war-criminals. Well, I could not let that pass unchallenged; and, although the leader of our canvassing team was urging me to move onwards, I remained for a good half an hour. We talked, at first fairly heatedly. but then more calmly. I did not myself support the invasion; but I reviewed the case for ousting Saddam Hussein; and I also talked about the immediacy of politics – the need for snap decisions; and the non-stop debates within as well as between the political parties.

By the end, the voter thanked me. She had not changed her mind – nor had I tried to change it for her. But she understood why I remained in the Labour Party – and she was glad that I’d stayed to talk through the issues.

Such moments made the whole procedure worthwhile. Rational democracy in action! And there have been plenty of other doorstep debates, though usually less basic than rebutting accusations of war-criminality.

Yet … I also learned that politics is not always about considered deliberations. There is scope too for quick and pointed repartee. Once, when first canvassing with my father in Sidcup, a voter asked on the doorstep with real anger in his voice: ‘What about the Labour Government’s failed groundnut scheme?’ 3 I then knew nothing of the issue (and cannot claim much expertise now!) Fortunately, my father was at a nearby doorstep. Quickly, I asked the voter to wait and ran over to consult my canvassing mentor. He said: ‘Go back and ask in reply: “What about Suez?”’4 I promptly did so. The voter stopped ranting and muttered ‘Oh yes, you’ve got a point there!’ He confirmed that he’d vote Labour – and I learned the value of smart repartee.

So there we are! In the big political battles, doorstep canvassers are mere foot-soldiers in the trenches. They know that. And the voters know it too. Yet, as already noted, these doorstep consultations are usually conducted politely. Voters may not want to see you at the moment that you call. But they do like to know that the political parties are out-and-about in the neighbourhood, talking to voters and picking up on local issues and casework. If there is no canvassing, there are liable to be complaints of: ‘We never see you!’ But they do often see Labour canvassers in Battersea, where I now live. It’s good for the voters; and educational for the canvassers too! ‘What about the groundnut scheme?’ … ‘Well, what about Suez?’ Long live doorstep democracy!

ENDNOTES:

1 See e.g. R. Behr, Politics – A Survivor’s Guide: How to Stay Involved without Getting Enraged (London, 2024).

2 For Charles James Fox (1749-1806), see L.G. Mitchell, Charles James Fox (Oxford, 1992); and for context, consult the impressive website on ‘Eighteenth-Century Political Participation and Electoral Culture’: https://ecppec.ncl.ac.uk.

3 For the Labour government’s project in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) the mid-1940s, see A. Wood, The Groundnut Affair (London, 1950); and N. Westcott, Imperialism and Development: The East African Groundnut Scheme and its Legacy (Woodbridge, 2020).

4 For the Anglo-French 1956 invasion of Egypt, see H. Thomas, The Suez Affair (London, 1967); S. Lucas, Britain and Suez: The Lion’s Last Roar (Manchester, 1996); and K. Kyle, Suez: Britain’s End of Empire in the Middle East (London, 2003).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 162 please click here

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.