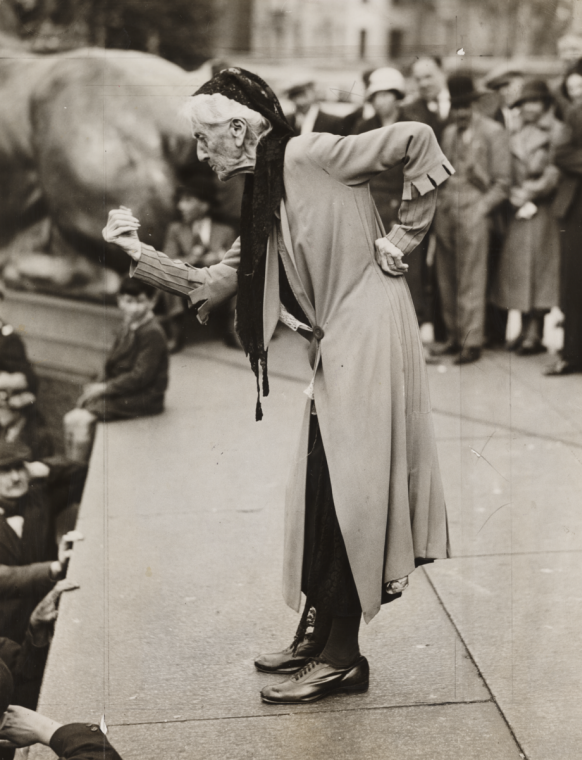

MONTHLY BLOG 144, A YEAR OF GEORGIAN CELEBRATIONS – 12: Celebrating the annual late-November Jonathan Swift Festival in the City of Dublin, where the Anglo-Irish wit, satirist and cleric was born and where he served as Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral from 1713 to 1745.

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2022)

|

Marble Bust of Jonathan Swift (1749) |

Where does humour come from? It’s a great question to ask, when contemplating the life and times of the twelfth hero in my year of Georgian commemorations. The Anglo-Irish Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) was an exceptionally sharp and witty man.1 Many jokes and wisecracks in circulation throughout the eighteenth century turn out, upon close inspection, to have derived from Swift.

Yet his position in life made him an unlikely public humourist. He was an Anglican clergyman, who rose to the position of Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin – dignified enough, albeit below the rank of a Bishop. At the same time, Swift was becoming renowned as an essayist, a political pamphleteer, a novelist, a poet, and a satirist, whose preoccupations included a scatological frankness that was unusual in any era. His unexpurgated verses on ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’ (1732)2 hymn the disgust of the spying lover who discovers that his radiant Celia is an earth-bound mortal: ‘Oh! Celia, Celia, Celia, shits!’

Such eclectic interests and activities do not necessarily preclude a clerical career. Plenty of ministers of the faith have a kindly sense of humour. Yet the combination of a sharply irreverent laughter with a soberly reverent faith is comparatively unusual, to say the least.

Other than Jonathan Swift, the most celebrated clerical wit in Britain in the long eighteenth century – running from c.1680 to 1830 – was Sydney Smith (1771-1845). He too was an Anglican minister, who became famed as a wit, polemicist and preacher. Yet there were not many men like these two – and Smith, like Swift, was never promoted to a Bishopric.3

Sardonic humour was seen by ecclesiastical patrons as a risky companion to piety. ‘Promises and pie-crusts are made to be broken’, commented Jonathan Swift. Apt enough – but such a cheery dictum might not be understood as the words of the strictest Christian moralist.

In fact, Swift in the pulpit was an urgent and compelling preacher, whose sermons in Dublin on every fifth Sunday were very popular.4 He sought to expound religious precepts in plain terms, that all could understand. And Swift bluntly warned young men starting their clerical careers to avoid sallies of wit from the pulpit: ‘because … it is very near a Million to one that you have none’.

Nonetheless, he was too much his own man to make him an easy candidate for church patronage. Swift sought to tell the truth as he saw it – and he avoided empty pieties. Moreover, he often sounded like a secularist, far above the mundane struggles of the rival faiths. ‘We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one another’, Swift observed in 1706.5 Apt again, but somehow cool and very definitely non-sectarian.

During his lifetime as a polemicist, indeed, Swift’s viewpoints were always robustly personal. In the 1710s he was aligned with the High Church-and-King political group in England, known as the Tories. Yet the pro-Tory Queen Anne, offended by Swift’s bluntness, denied him any substantial clerical promotion. Then in the 1720s and 1730s, the moderate reform Whigs took over. Swift had no further hopes of clerical advancement in England. He retreated to his Dublin Deanery, to live ‘like a rat in a hole’, as he wrote, ungraciously.

Residence in Ireland, however, brought significant new issues to his attention. Swift polemicised vigorously on behalf of Irish causes. Published in 1729, his Modest Proposal for Preventing the Poor Children in Ireland from being a Burden to their Parents or Country [by being eaten as delicacies] remains one of the most savage polemics, under the guise of sweet reason, ever written. Swift did not define himself as an ‘Irish patriot’. Yet it is no surprise to find that he has later become hailed as a nationalist hero.6

Swift faced life’s twists and turns with an intent intelligence and coruscating wit, which were allied (as he specified in his auto-epitaph) with a ‘savage indignation’. He’d had a disrupted childhood. His father predeceased the son’s birth, leaving Swift in the care of a paternal uncle. The mother returned to England, leaving the baby with a wet-nurse, who took him to Cumberland. Two years later, the child was parted from his nurse, and returned to his uncle’s care in Ireland. Later, as an adult, Swift had an unpleasant disorder of the inner ear, which gave him nausea and vertigo. He never married but he had fervent friendships with a few favoured female friends (how fervent remains debated). And he wrote and wrote, voluminously.

So where did the humour come from? His disturbed life experiences might have promoted both intensity and insecurity. But not necessarily humour. At the same time, it’s likely that the witty Anglo-Irish Swift, who was born in Dublin to English parents, would draw from the jesting cultures in which he was immersed. He was thus acquainted with English ‘deadpan’ humour and irony,7 as well as with the closely-related Irish traditions of whimsy and wordplay.

Cultural traditions provide fodder for the creative imagination. Think of Gulliver’s Travels. Could Lilliputia, with its diminutive citizens, have drawn some inspiration from traditional Irish tales of ‘little folk’ and leprechauns?8 Gulliver then visits Brobdingnag, a land of giants. Had Swift heard Irish tales of the exceptionally tall people of Antrim? (Interestingly, scientists today confirm that there is a ‘giant hotspot’ in that region, where an unusually high proportion of the population have a genetic predisposition to be very tall).9 And Gulliver later explores the flying island of Laputa, peopled by ‘mad’ scientists. How far did Swift’s sardonic improvisation rely upon his own familiarity with Stuart England’s lively culture of scientific experimentalism?10

But, of course, the creation in 1726 of an original masterpiece of world literature came from one man only. No doubt, there were some Anglo-Irishmen in these years, who had no sense of humour. And there may have been others, who were very jovial but never set pen to paper.

Jonathan Swift once remarked that: ‘Vision is the art of seeing what is invisible to others’.11 He had that gift. And he conveyed his vision in a memorably sardonic style. It’s appropriate therefore that the world should both commemorate his achievements – and laugh. After all, as Swift aptly noted in 1733 (extending his earlier jibe at novice clergymen):12

All Human Race would fain be Wits,

And Millions miss, for one that hits.

ENDNOTES:

1 See I. Ehrenpreis, The Personality of Jonathan Swift (London, 1958); D. Johnston, In Search of Swift Dublin, 1959); I. Ehrenpreis, Swift: The Man, his Works and the Age, Vols. 1-3 (1962-83; repr. 2021); D. Nokes, Jonathan Swift – A Hypocrite Reversed: A Critical Biography (Oxford, 1985; 1987); L. Damrosch, Jonathan Swift: His Life and his World (New Haven, Conn., 2013); D. Oakleaf, A Political Biography of Jonathan Swift (London, 2015); J. Stubbs, Jonathan Swift: The Reluctant Rebel (London, 2016).

2 J. Swift, ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’ (1732; slightly corrected 1735); in unexpurgated version in website: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50579/the-ladys-dressing-room (consulted 30 Nov. 2022).

3 H. Pearson, The Smith of Smiths: Being the Life, Wit and Humour of Sydney Smith (London, 1934; and later edns); A.S. Bell, Sydney Smith, Rector of Foston, 1806-29 (York, 1972; Oxford, 1980); P. Virgin, Sydney Smith (London, 1994).

4 See website https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sermons_of_Jonathan_Swift (consulted 30 Nov 2022); and context in L.A. Landa, Swift and the Church of Ireland (Oxford, 1954).

5 J. Swift, Thoughts on Various Subjects, Moral and Diverting, in J. Hawkesworth (ed.), The Works of Jonathan Swift, D.D. of St Patrick’s Dublin, Vol. 2 (1755).

6 O.W. Ferguson, Jonathan Swift and Ireland (Urbana, Ill., 1962).

7 H.J. Davis, ‘Swift’s Use of Irony’ in M.E. Novak and H.J. Davis (eds), The Uses of Irony: Papers on Defoe and Swift (Los Angeles, Calif., 1966), pp. 41-63. For contextual discussions, see also J.B. Priestley, English Humour (London, 1929); H. Nicolson, The English Sense of Humour: An Essay (London, 1946); B.J. Blake, Playing the Words: Humour in the English Language (London, 2007).

8 See e.g. H. McGowan, Leprechauns, Legends and Irish Tales (London, 1988).

9 See report in Daily Mail (October 2016), available in website: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3834804/Land-Celtic-giants-Northern-Ireland-revealed-hotspot-abnormally-tall-people.html (consulted 30 Nov. 2022). It was this part of Ireland that produced Charles Byrne, the ‘Irish Giant’, who was put exhibited in London in the 1780s as a human curiosity.

10 M. Hunter, Science and the Shape of Orthodoxy: Intellectual Change in Late Seventeenth-Century Britain (Woodbridge, 1995)

11 Swift, Thoughts on Various Subjects, in Hawkesworth (ed.), Works of Jonathan Swift, Vol. 2 (1755).

12 J. Swift, ‘On Poesy: A Rhapsody’ (1733), in H. Davis (ed.), Swift: Poetical Works (London, 1967), p. 569. This volume also contains an expurgated version of Swift on ‘The Lady’s Dressing Room’ (cited above, n.2), pp. 476-80.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 144 please click here