MONTHLY BLOG 27, ASKING QUESTIONS POST SEMINAR PAPERS/LECTURES

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2013)

What? what? what? Always good to ask questions. Not always easy to manage a good one. In the debates following the thousands of public lectures and seminar papers that I’ve heard, a few examples stand out.

One was simplicity itself. It caught out a senior figure on a point of detail that refuted her argument – which she should have known but didn’t (or had forgotten). The question took five words: ‘What about the Quebec Act?’ Under this legislation (1774) Britain allowed freedom of worship to the French-speaking Quebec Catholics and enabled them to swear allegiance to the British crown without reference to Protestantism. It was a major factor in preventing the potentially rebellious province from joining the American colonial revolt. This flexibility ran contrary to the speaker’s stress upon the immovable Protestantism of eighteenth-century British state policy. There were various possible replies, such as: it was the exception to prove the rule. But she fell silent and the chair took the next question. Since then, I often think, when listening to a lecture: Is there a Quebec Act equivalent knock-down? Often there isn’t. But, if there is, it should always be done with great simplicity.

Another was a question that I asked after a public lecture (not necessarily the best; simply one that I remember). In fact, interventions from the floor are much more forgettable than the preceding oration, which is one reason not to worry too much about what to ask. In this case, a polemical speaker had castigated all historians who used anachronistic terms instead of sticking exclusively to the language of the relevant past period. Then, oblivious of his own strictures, he defined the eighteenth-century European states (including Britain) as ancien regimes. But – whether ‘ancien’ be translated as ‘old’ or ‘former’ – this descriptive term is clearly retrospective. From the floor, I argued that the historians’ art entails not only studying past societies but also communicating their findings about the past in the language of a later day. So yes to linguistic care and attention to definitions; but no to linguistic obscurantism and a quest for the impossible. Otherwise historians of pre-Conquest England would have to delete all words derived from Norman French; historians of the pre-speech era would have to grunt; and so forth. In the light of his own retrospective terminology, would the speaker like to reconsider his criticisms of others? He replied; but, it was generally agreed, not convincingly.

Those two examples reveal two possible approaches to asking questions: either working from prior knowledge; or generating a debating point from the content of the talk. Both approaches are equally valid. The point of asking questions is constructive: to probe the case that has been presented and to extend the collective discussion. A good debate helps speakers by giving them a free consultancy, allowing them to refine their arguments before bursting into print. And ditto: good discussions help listeners to stretch their minds; to learn how to joust intellectually; and to contribute to the advancement of knowledge.

Obviously enough, beginners giving their first paper should be treated comparatively gently, but not to the extent of allowing serious errors to pass unchallenged. And senior performers should be given the compliment of a bracing set of questions, which they will expect.

Most enquiries start from a wholesome quest for further information or clarification. What did you mean by statement A? How do you define concept B? Did you also check source C? … How good is the evidence for X? Can that proposition not be tested against Y? And what are the implications of Z? All of those approaches are useful. Another substantial range of questions focus upon the speakers’ methods of classification, selection, or organisation of research material. Challenges are especially required if the criteria have not been well explained in the presentation. Social classification systems, in particular, always benefit from debate, whether focusing upon class; ethnicity; nationality; or any other special identities. One phenomenon that is often under-studied is the extent of intermarriage between ostensibly different groups: ask about that.

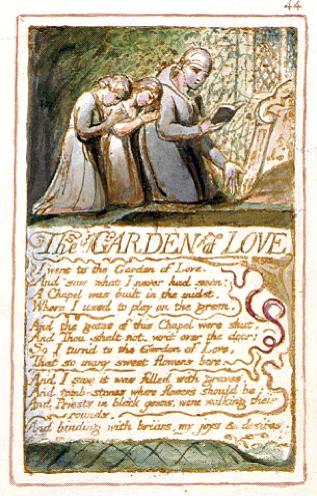

Meanwhile, a minority of questions, which are often the best, take the form of a conceptual or philosophical depth-charge or counter-argument. Listen to the general argument and think: could the reverse or something very different be the case instead? That may mean playing devil’s advocate. But, intellectually, ‘opposition is true friendship’, to quote William Blake.1 Above all, it’s good to listen closely to the speakers, in order to identify their often-buried fundamental assumptions – and then challenge those. It’s rare that such interventions fail to stimulate. Sometimes speakers are surprised; sometimes indignant; but they are generally gratified to have been listened to with serious attention.

|

From William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell (Bodleian Library copy, 1790, fo. 20) |

My former supervisor, Jack Fisher, the economic history guru of LSE, was famed for provocative depth-charges, which he signalled with the opening words: ‘I know nothing about this but …’. However, his formula is best used sparingly. I have heard others bodge the same tactic, leading audiences to wonder why such a self-declared ignoramus is wasting everyone’s time with fatuous questions.

Given the above range of possibilities, postgraduate students should be encouraged to start with short, punchy wholesome-quests-for-information. In that way, they get used to the invariable stir of people turning round to look at the questioner, which can be disconcerting for beginners. Then, in time, students should progress to making longer enquiries and eventually to offering counter-arguments. My own system also requires that, after the first term at a new seminar, postgraduates ask at least one question per term, rising to a specified larger number as they move through their four years of study. That instruction sounds a bit mechanical. But it’s actually easier to ask a question when one has determined beforehand to do so. Otherwise, a lot of time is spent dithering: shall I, shan’t I? Yes, go for it.

Coda: I’ll end with a personal anecdote on heckling. It’s not something that I often do. But once I heckled, unintentionally, and found that I had posed a great question or, rather, prompted a great response. It happened in the early 1970s, at a public debate in the University of London’s Beveridge Hall, with perhaps two hundred dons in attendance. Two eminent historians, Keith Thomas and Hugh Trevor-Roper, had jousted fiercely in print about seventeenth-century witchcraft. They were invited to a special debate to continue the argument. But face-to-face, as often happens, the antagonists were very polite to each other. The occasion as a whole proved to be a damp squib.

There was, however, a moment of excitement. One of the speakers, referred rather contemptuously to ‘useless old women’ and, without intending to do so, I found that I had cried out ‘Shame!’ Everyone around me recoiled. The speakers said nothing. But the chair of the meeting, the historian Joel Hurstfield, responded with aplomb: ‘Madam, contain your just indignation!’ His old-fashioned courtesy effectively rebuked my uncouthness. Yet he upheld my complaint, accepting that the tone of the debate had been too dismissive of the women accused of witchcraft. Immediately, the people around me smiled with relief and reversed their physical recoil. The debate was resumed, and I don’t suppose anyone else remembers the exchange. Nonetheless, I have waited ever since (both in politics and as an academic) for someone to heckle when I’m in the chair, to see if I can respond as brilliantly. It hasn’t happened yet; but maybe one day … In the meantime, let there be questions: what? what? what?

1 From William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793), fol. 20.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 27 please click here