If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2015)

Vote early! Generations of democratic activists have campaigned over centuries to give the franchise to all adult citizens. (Yes, and that right should extend to all citizens who are in prison too).2 Vote early and be proud to vote!

So, if we are full of civic pride or even just wearily acquiescent, why don’t we vote openly? Stand up to be counted? That is, after all, how the voting process was first done. In most parliamentary elections in pre-democratic England (remembering that not all seats were regularly contested), the returning officer would simply call for a show of hands. If there was a clear winner, the result would be declared instantly. But in cases of doubt or disagreement a head-by-head count was ordered. It was known as a ‘poll’. Each elector in turn approached the polling booth, identified his qualifications for voting, and called his vote aloud.3

|

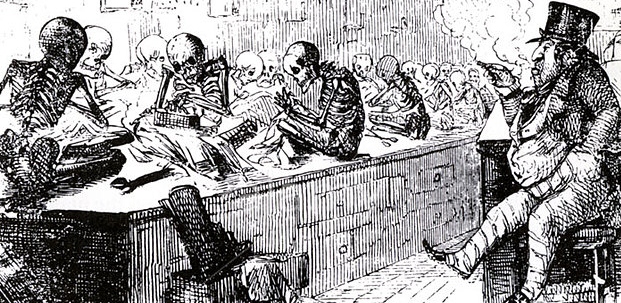

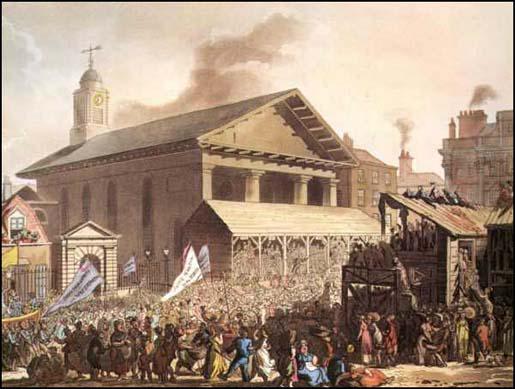

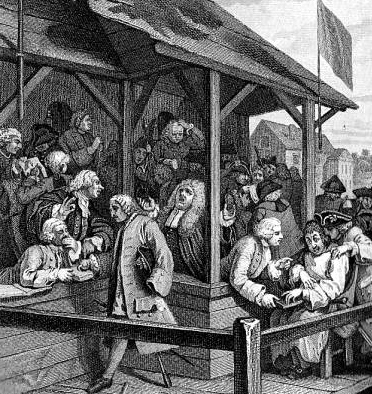

William Hogarth’s Oxfordshire Election (1754) satirised the votes of the halt, the sick and the lame. Nonetheless, he shows the process of open voting in action, with officials checking the voters’ credentials, lawyers arguing, and candidates (at the back of the booth) whiling away the time, as voters declare their qualifications and call out their votes.

|

Open voting was the ‘manly’ thing to do, both literally and morally. Not only was the franchise, for many centuries, restricted to men;4 but polling was properly viewed as an exercise of constitutional virility. The electoral franchise was something special. It was a trust, which should be exercised accountably. Hence an Englishman should be proud to cast his vote openly, argued the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill in 1861.5 He should cast his vote for the general good, rather than his personal interest. In other words, the elector was acting as a public citizen, before the eyes of the world – and, upon important occasions, his neighbours did come to hear the verdict being delivered. Furthermore, in many cases the Poll Books were published afterwards, so generating a historical record not only for contemporaries to peruse, and for canvassers to use at the following election, but also for later historians to study individual level voting (something impossible under today’s secret ballot).

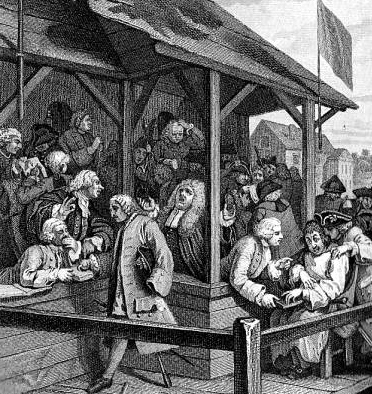

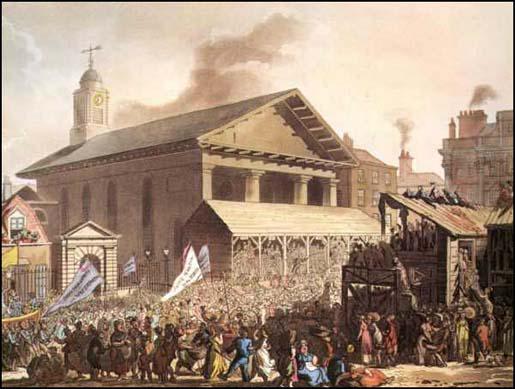

Especially in the populous urban constituencies, some of the most protracted elections became carnival-like events.6 Crowds of voters and non-voters gathered at the open polling booths to cheer, heckle or boo the rival candidates. They sported election ribbons or cockades; and drank at the nearby hostelries. Since polling was sometimes extended over several days, running tallies of the state of the poll were posted daily, thus encouraging further efforts from the canvassers and the rival crowds of supporters. Sometimes, indeed, the partisanship got out of hand. There were election scuffles, affrays and even (rarely) riots. But generally, the crowds were good-humoured, peaceable and even playful. In a City of Westminster parliamentary by-election in 1819, for example, the hustings oratory from the candidate George Lamb was rendered inaudible by incessant Baaing from the onlookers. It was amusing for everyone but the candidate, though he did at least win.7

Performing one’s electoral duty openly was a practice that was widely known in constitutionalist systems around the world. Open voting continued in Britain until 1872; in some American states until 1898; in Denmark until 1900; in Prussia until 1918; and, remarkably, in Hungary until 1938.

Not only did the voter declare his stance publicly but the onlookers were simultaneously entitled to query his right to participate. Then the polling clerks, who sat at the hustings to record each vote, would check in the parish rate books (or appropriate records depending each variant local franchise) before the vote was cast.8 In the event of a subsequent challenge, moreover, the process was subject to vote-by-vote scrutiny. One elector at a parliamentary by-election in Westminster in 1734 was accused by several witnesses of being a foreigner. He was said to have a Dutch accent, a Dutch coat, and to smoke his pipe ‘like a Dutchman’. Hence ‘it is the common repute of the neighbourhood that he is a Dutchman’.9 In fact, the suspect, named Peter Harris, was a chandler living in Wardour Street and he outfaced his critics. The neighbours’ suspicions were not upheld and the vote remained valid. Nonetheless, public opinion had had a chance to intervene. Scrutiny of the electoral process remains crucial, now as then.

|

Illustration/2: British satirical cartoon of Mynheer Van Funk, a Dutch Skipper (1730)

Was this what Peter Harris, of Wardour Street, Westminster, looked like?

|

Well then, why has open voting in parliamentary elections disappeared everywhere? There are good reasons. But there is also some loss as well as gain in the change. Now people can make a parade of their commitment (say) to some fashionable cause and yet, sneakily, vote against it in the polling booth. Talk about having one’s cake and eating it. That two-ways-facing factor explains why sometimes prior opinion polls or even immediate exit polls can give erroneous predictions of the actual result.

Overwhelmingly, however, the secret ballot was introduced to allow individual voters to withstand external pressures, which might otherwise encourage them to vote publicly against their true inner convictions. In agricultural constituencies, tenants might be unduly influenced by the great local landlord. In single-industry towns, industrial workers might be unduly influenced by the big local employer. In service and retail towns, shopkeepers and professionals might be unduly influenced by the desire not to offend rich clients and customers. And everywhere, voters might be unduly influenced by the power of majority opinion, especially if loudly expressed by crowds pressing around the polling booth.

For those reasons, the right to privacy in voting was one of the six core demands made in the 1830s by Britain’s mass democratic movement known as Chartism.10 In fact, it was the first plank of their programme to be implemented. The Ballot Act was enacted in 1872, long before all adult males – let alone all adult females – had the vote. It was passed just before the death in 1873 of John Stuart Mill, who had tried to convince his fellow reformers to retain the system of open voting. (By the way, five points of the six-point Chartist programme have today been achieved, although the Chartist demand for annual parliaments remains unmet and is not much called for these days).

Does the actual voting process really matter? Secrecy allows people to get away with things that they might not wish to acknowledge publicly. They can vote frivolously and disclaim responsibility. Would the Monster Raving Loony Party get as many votes as it does (admittedly, not many) under a system of open voting? But I suppose that such votes are really the equivalent of spoilt ballot papers.

In general, then, there are good arguments, on John Stuart Millian grounds, for favouring public accountability wherever possible. MPs in Parliament have their votes recorded publicly – and rightly so. Indeed, in that context, it was good to learn recently that a last-minute bid by the outgoing Coalition Government of 2010-15 to switch the electoral rules for choosing the next Speaker from open voting to secret ballot was defeated, by a majority of votes from Labour plus 23 Conservative rebels and 10 Liberal Democrats. One unintentionally droll moment came when the MP moving the motion for change, the departing Conservative MP William Hague, defended the innovation as something ‘which the public wanted’.11

Electoral processes, however, are rarely matters of concern to electors – indeed, not as much as they should be. Overall, there is a good case for using the secret ballot in all mass elections, to avoid external pressures upon the voters. There is also a reasonable case for secrecy when individuals are voting, in small groups, clubs, or societies, to elect named individuals to specific offices. Otherwise, it might be hard (say) not to vote for a friend who is not really up to the job. (But MPs choosing the Speaker are voting as representatives of their constituencies, to whom their votes should be accountable). In addition, the long-term secrecy of jury deliberations and votes is another example that is amply justified in order to free jurors from intimidation or subsequent retribution.

But, in all circumstances, conscientious electors should always cast their votes in a manner that they would be prepared to defend, were their decision known publicly. And, in all circumstances, the precise totals of votes cast in secret ballots should be revealed. The custom in some small societies or groups, to announce merely that X or Y is elected but to refrain from reporting the number of votes cast, is open to serious abuse. Proper scrutiny of the voting process and the outcome is the democratic essence, along with fair electoral rules.

In Britain, as elsewhere, there is still scope for further improvements to the workings of the system. The lack of thoroughness in getting entitled citizens onto the voting register is the first scandal, which should be tackled even before the related question of electoral redistricting to produce much greater equality in the size of constituencies. It’s also essential to trust the Boundaries Commission which regularly redraws constituency boundaries (one of the six demands of the Chartists) to do so without political interference and gerrymandering. There are also continuing arguments about the rights and wrongs of the first-past-the-post system as compared with various forms of Alternative Voting.

Yet we are on a democratic pathway …. Hence, even if parliamentary elections are no longer occasions for carnival crowds to attend as collective witnesses at the hustings, let’s value our roles individually. The days of open voting showed that there’s enjoyment to be found in civic participation.

|

Thomas Rowlandson’s Westminster Election (published 1808), showing the polling booths in front of St Paul’s Covent Garden – and the carnivalesque crowds, coming either to vote or to witness.

|

1 With warm thanks to Edmund Green for sharing his research, and to Tony Belton, Helen Berry, Arthur Burns, Amanda Goodrich, Charles Harvey, Tim Hitchcock, Joanna Innes, and all participants at research seminars at London and Newcastle Universities for good debates.

2 On this, see A. Belton, BLOG entitled ‘Prisoners and the Right to Vote’, (2012), tonybelton.wordpress.com/2012/12/04/prisoners-and-the-right-to-vote/.

3 See J. Elklit, ‘Open Voting’, in R. Rose (ed.), International Encyclopaedia of Elections (2000), pp. 191-3; and outcomes of open voting in metropolitan London, 1700-1850, in www.londonelectoralhistory.com, incl. esp. section 2.1.1.

4 In Britain, adult women aged over 30 first got the vote for parliamentary elections in 1918; but women aged between 21 and 30 (the so-called ‘flappers’) not until 1928.

5 J.S. Mill, Considerations on Representative Government (1861), ed. C.V. Shields (New York, 1958), pp. 154-71.

6> See F. O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons and Parties: The Unreformed Electorate of Hanoverian England, 1734-1832 (Oxford, 1989).

7 British Library, Broughton Papers, Add. MS 56,540, fo. 55. Lamb then lost the seat at the next general election in 1820.

8 Before the 1832 Reform Act, there was no standardised electoral register; and many variant franchises, especially in the parliamentary boroughs.

9 Report of 1734 Westminster Scrutiny in British Library, Lansdowne MS 509a, fos. 286-7.

10 For a good overview, consult M. Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester, 2007).

11 BBC News, 26 March 2015: www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-32061097.

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 53 please click here