MONTHLY BLOG 95, ‘WHAT IS THE GREATEST SIN IN THE WORLD?’ CHRISTOPHER HILL AND THE SPIRIT OF EQUALITY

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2018)

Text of short talk given by PJC to introduce the First Christopher Hill Memorial Lecture, (given by Prof. Justin Champion) at Newark National Civil War Centre, on Saturday 3 November 2018.

Christopher Hill was not only a remarkable historian – he was also a remarkable person.1 All his life, he believed, simply and staunchly, in human equality. But he didn’t parade his beliefs on his sleeve. At first meeting, you would have found him a very reserved, very solid citizen. And that’s because he was very reserved – and he was solid in the best sense of that term. He was of medium height, so did not tower over the crowd. But he held himself very erect; had a notably sturdy, broad-shouldered Yorkshire frame; and was very fit, cycling and walking everywhere. And in particular, Christopher Hill had a noble head, with a high forehead, quizzical eyebrows, and dark hair which rose almost vertically – giving him, especially in his later years, the look of a wise owl.

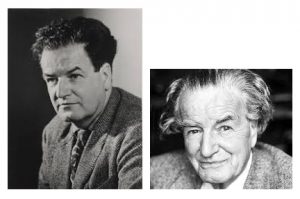

| Christopher Hill (L) in his thirties and (R) in his seventies |

By the way, he was not a flashy dresser. The Hill family motto was ‘No fuss’. And, if you compare the two portraits of him in his 30s and his 70s, you could be forgiven for thinking that he was wearing the same grey twill jacket in both. (He wasn’t; but he certainly stuck to the same style all his life).

Yet even while Christopher Hill was reserved and dignified, he was also a benign figure. He had no side. He did not pull rank. He did not demand star treatment. He was courteous to all – and always interested in what others had to say. That was a key point. As Master of Balliol, Hill gave famous parties, at which dons and students mingled; and he was often at the centre of a witty crowd. But just as much, he might be found in a corner of the room discussing the problems of the world with a shy unknown.

As I’ve already said. Christopher Hill believed absolutely in the spirit of equality. But he did know that it was a hard thing to achieve – and that was why he loved the radicals in the English civil wars of the mid-seventeenth century. They were outsiders who sought new ways of organising politics and religion. Indeed, they struggled not only to define equality – but to live it. And, although there was sometimes a comic side to their actions, he admired their efforts.

When I refer to unintentionally comic aspects, I am thinking of those Ranters, from the radical and distinctly inchoate religious group, who jumped up in church and threw off their clothes as a sign. The sign was that they were all God’s children, equal in a state of nature. Not surprisingly, such behaviour attracted a lot of criticism – and satirists had good fun at their expense.

Well, Christopher Hill was far too dignified to go around throwing off his clothes. But he grew up believing a radical form of Methodism, which stressed that ‘we are all one in the eyes of the Lord’. As I’ve said, his egalitarianism came from within. But he was clearly influenced by his Methodist upbringing. His parents were kindly people, who lived simply and modestly (neither too richly nor too poorly). They didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, didn’t swear and didn’t make whoopee. Twice and sometimes even three times on Sundays, they rode their bikes for several miles to and from York’s Central Methodist Chapel; and then discussed the sermon over lunch.

In his mid-teens, Hill was particularly inspired by a radical Methodist preacher. He was named T.S. Gregory and he urged a passionate spiritual egalitarianism. Years later, Hill reproduced for me Gregory’s dramatic pulpit style. He almost threw himself across the lectern and spoke with great emphasis: ‘Go out into the streets – and look into the eyes of every fellow sinner, even the poorest beggar or the most abandoned prostitute; [today he would add look under the hoods of the druggies and youth gangs]; look into these outcast faces and in every individual you will see elements of the divine’. The York Methodists, from respectable middle class backgrounds, were nonplussed. But Hill was deeply stirred. For him, Gregory voiced a true Protestantism – which Hill defined as wine in contrast with what he saw as the vinegar and negativism of later Puritanism.

The influence of Gregory was, however, not enough to prevent Hill in his late teens from losing his religious faith. My mother, Christopher’s younger sister, was very pleased at this news as she welcomed his reinforcement. She herself had never believed in God, even though she too went regularly to chapel. But their parents were sincerely grieved. On one occasion, there was a dreadful family scene, when Christopher, on vacation from Oxford University, took his younger sister to the York theatre. Neither he nor my mother could later remember the show. But they both vividly recalled their parent’s horror: going to the theatre – abode of the devil! Not that the senior Hills shouted or rowed. That was not their way. But they conveyed their consternation in total silence … which was difficult for them all to overcome.

As he lost his faith, Hill converted to a secular philosophy, which had some elements of a religion to it. That was Marxism. Accordingly, he joined the British Communist Party. And he never wavered in his commitment to a broad-based humanist Marxism, even when he resigned from the CP in 1956. Hill was not at all interested in the ceremonies and ritual of religion. The attraction of Marxism for him was its overall philosophy. He was convinced that the revolutionary unfolding of history would eventually remove injustices in this world and usher in true equality. Hill sought what we would call a ‘holistic vision’. But the mover of change was now History rather than God.

On those grounds, Hill for many years supported Russian communism as the lead force in the unfolding of History. In 1956, however, the Soviet invasion of Hungary heightened a fierce internal debate within the British Communist Party. Hill and a number of his fellow Marxist historians, struggled to democratise the CP. But they lost and most of them thereupon resigned.

This outcome was a major blow to Hill. Twice he had committed to a unifying faith and twice he found its worldly embodiment unworthy. Soviet Communism had turned from intellectual inspiration into a system based upon gulags, torture and terror. Hill never regretted his support for Soviet Russia during the Second World War; but he did later admit that, afterwards, he had supported Stalinism for too long. The mid-1950s was an unhappy time for him both politically and personally. But, publicly, he did not wail or beat his breast. Again, that was not the Hill way.

He did not move across the political spectrum, as some former communists did, to espouse right-wing causes. Nor did he become disillusioned or bitter. Nor indeed, did he drop everything to go and join a commune. Instead, Hill concentrated even more upon his teaching and writing. He did actually join the Labour Party. Yet, as you can imagine, his heart was not really in it.

It was through his historical writings, therefore, that Hill ultimately explored the dilemmas of how humans could live together in a spirit of equality. The seventeenth-century conflicts were for him seminal. Hill did not seek to warp history to fit his views. He could not make the radicals win, when they didn’t. But he celebrated their struggles. For Hill, the seventeenth-century religious arguments were not arid but were evidence of the sincere quest to read God’s message. He had once tried to do that himself. And the seventeenth-century political contests were equally vivid for him, as he too had been part of an organised movement which had struggled to embody the momentum of history.

As I say, twice his confidence in the worldly formulations of his cause failed. Yet his belief in egalitarianism did not. Personally, he became happy in his second marriage; and he immersed himself in his work as a historian. From being a scholar who wrote little, he became super-productive. Books and essays poured from his pen. Among those he studied was the one seventeenth-century radical who appealed to him above all others: Gerrard Winstanley, the Digger, who founded an agrarian commune in the Surrey hills. And the passage in Winstanley’s Law of Freedom (1652) that Hill loved best was dramatic in the best T.S. Gregory style. What is the greatest sin in the world? demanded Winstanley. And he answered emphatically that it is for rich people to hoard gold and silver, while poor people suffer from hunger and want.

What Hill would say today, at the ever widening inequalities across the world, is not hard to guess. But he would also say: don’t lose faith in the spirit of equality. It is a basic tenet of human life. And all who believe in fair does for all, as part of true freedom, should strive to find our own best way, individually and/or collectively, to do our best for our fellow humans and to advance Hill’s Good Old Cause.

1 For documentation, see P.J. Corfield, ‘“We are all One in the Eyes of the Lord”: Christopher Hill and the Historical Meanings of Radical Religion’, History Workshop Journal, 58 (2004), pp. 110-27. Now posted on PJC personal website as Pdf5; and further web-posted essays PJC Pdf47-50, all on www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 95 please click here