If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2016)

I voted REMAIN in the great Europe-referendum of June 2016, and was sorry (though not distraught) to find myself in the minority. At the same time, I had reservations about the European Union, not least for its lack of clear political accountability. In particular, I worry about the anomalous position of the EU’s European Parliament, whose impotence makes a mockery of democratic constitutionalism. So what precisely is wrong? The constitution of the European Union is a peculiar hybrid, which has emerged through a series of eclectic compromises. Nothing intrinsically wrong with that. That’s history. Even the most carefully wrought constitutions need amendment from time to time, to take account of changing times and new or altered expectations. But, if the contradictions are too glaring, then problems follow. Currently, the EU seems not only leaderless but rudderless. And there’s no easy way for Europe’s electorates to put democratic pressure on the system for structural changes, other than by expressing negative responses to Euro-referenda. Britain in June 2016 has done exactly that.

There has long been a disjuncture between the Euro-rhetoric of ‘ever closer Union’, and the actual system of highly complex political horse-trading between the (currently) 28 sovereign member states of the European Union.1 Not only are there frequent exemptions and national opt-outs from every rule, but there are different sub-groupings with separate rules for specific purposes. As a result, it’s already established practice for variegated combinations of countries to negotiate over diverse policies, under a broad Euro-umbrella.

One of the two most important sub-groupings is the Schengen Area, which has no passport controls within its boundaries. It covers 22 member states from the EU, plus four further countries from the European Free Trade Area (EFTA): viz. Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland. From the start, Great Britain and Ireland had negotiated opt-outs; and very recently (2016) temporary controls have been restored by Austria, Denmark, Germany, Norway, Poland and Sweden. It seems probable that the Schengen policy won’t survive unscathed.

The second big sub-grouping is the Eurozone Area, established in January 1999, sharing a common currency. It embraces 19 of the 28 member states of the European Union.2 Denmark and the United Kingdom have negotiated opt-outs, but all new EU members are expected to join automatically. The Eurozone Area has the backing of a new European Central Bank. It seeks to manage the currency, with the aid of suitable fiscal and economic policies.3 Currently, however, the Eurozone is facing severe challenges; and it too may not survive unscathed.4

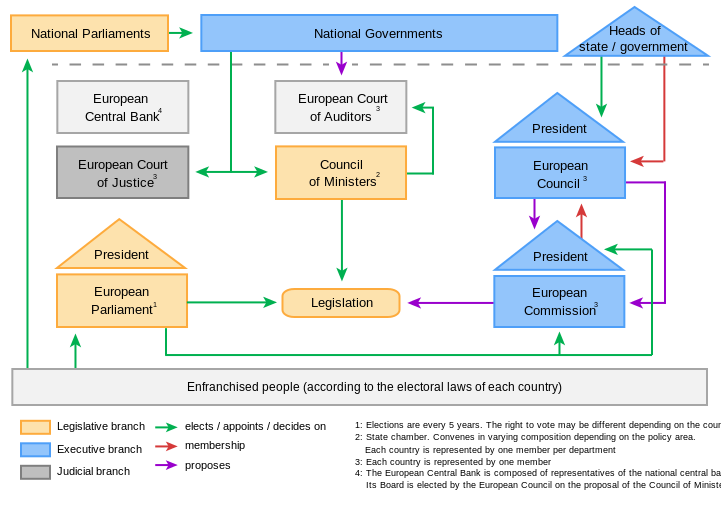

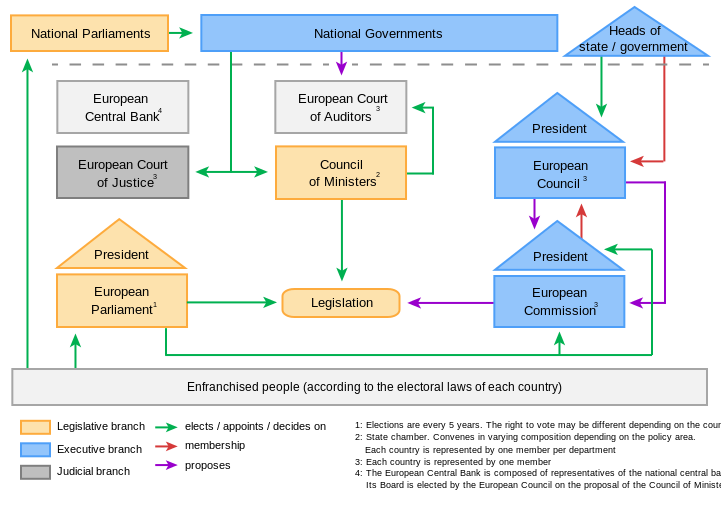

Constitutionally, the European Union operates as a close alliance or quasi- federation of sovereign states, which pool some of their powers in different combinations for different purposes. But there is a profusion of overlapping component institutions, with no clear lines of authority, while the sovereign states continue to protect their own interests, as their electorates expect.5 There is no collective legal body known as the United States of Europe. Nor is the European Union (the federation’s title as adopted in 1993 under the Maastricht Treaty) organisationally anything like either a fully federal body or a unitary state.

In terms of policy debates, law-making, and budget-setting, one prime forum is the Council of the European Union, attended by government ministers from all member countries. Its Presidency has no executive power but chairs meetings and helps to coordinate the agenda. Each country (currently Slovakia) holds this post in turn, on a six-month rotating basis. There is also a separate European Council, when EU leaders meet quarterly to set the broad agenda. This body appoints its own President (currently Poland’s Donald Tusk), who seeks to coordinate the different EU institutions and also represents the Union in foreign affairs. This post has prestige but, again, no executive powers. Nonetheless, insofar as constitutional comparisons can be made, this post is the nearest EU-equivalent to the post of President in a fully federal system, such as that of the USA.

Incidentally, these two Councils should not be confused with the Council of Europe, founded in 1949, which now includes as many as 47 European countries. Its remit, focusing chiefly upon the rule of law, provides the constituent authority for the European Court of Human Rights.6 Hence one key component of the judicial arm of the postwar European project operates at one remove from the European Union, although in the public debates (eg. over Brexit in June 2016) they are often linked. There is also a further Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which adjudicates over the rival status of national and European laws.

Separated entirely from all the above bodies is the European Commission. It is the equivalent of the executive branch of the EU’s constitution, implementing policy decisions, setting financial priorities, providing regulatory frameworks for governance, proposing new laws, and also representing the EU in foreign affairs. Yet – a key proviso – the Commission does not itself run the day-to-day government in any of the member states. It remains a sort of transnational super-executive, which attracts criticism for its high claims and controversial budgeting whilst being unable to win praise by running things efficiently at grass-roots level.

Today there are 28 Commissioners (one for every member state), each with a specialist brief. They are appointed by the European Council; and led by a Commission President (currently Luxembourg’s Jean-Claude Juncker), who allocates portfolios between the Commissioners. There are a number of areas of obvious overlap: for example, in foreign affairs, both the President of the European Council and the President of the European Commission have a claim to speak for the EU, whilst one Commissioner, who is also one of the Vice-Presidents, has the specific title of High Representative for the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The media sometimes describes this post as the EU’s Foreign Secretary, and the holder (currently Italy’s Federica Mogherini) is buttressed by a new European External Action Service, established under the Lisbon Treaty in 2010. A simplified model of all these interlinking authorities is shown in Fig.1.

Nonetheless, despite the formalities, on many issues it’s the leading politicians of the dominant sovereign states who make the real running. They meet in their own conclaves. The German Chancellor and the French President (from the two big countries at the core of the alliance) confer frequently. And in late August 2016 they met with the Italian Prime Minister at Ventotene, near Naples, for a trilateral mini-summit, in the wake of Britain’s Brexit vote.7 Immediately after that, the German Chancellor made diplomatic visits to Tallinn, Prague, and Warsaw, before returning to Germany to host individually the leaders of seven more EU states, as well as, no doubt, telephoning all the others. In other words, the uncrowned EU President is (currently) Angela Merkel – a role that she and her successors are likely to retain as long as German economic dominance within the EU is particularly upheld by the workings of the Euro currency union.

Where does all that leave the European Parliament? It is by no means democratically supreme. It does approve (or reject) the nominee for the post of European Commissioner, although it does not on its own authority choose a government or run an executive. Its budget-setting and law-making powers are also shared with the Council of the European Union, whilst proposals for new laws come from the Commissioners. But the Parliament does have a President (currently Germany’s Martin Schulz), further signalling the EU’s love of presidential titles.

|

Europe’s Presidents – Official and Unofficial:

Above (L) Donald Tusk, President of the Council of the European Union

(Centre) Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission

(R) Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament

Below: Angela Merkel, German Chancellor, Europe’s unofficial linchpin.

|

It’s hard not to consider the European Parliament as anything more than a democratic fig-leaf, although it has been given more powers in recent years. The institution was invented late in the European project (in 1979) to redress the lack of popular input. Its 751 members (MEPs), representing in aggregate (in 2009) a potential electorate of 375 million people, have the legitimacy of a direct European-wide mandate.8 In EU parlance, they constitute the ‘first institution’ and take ceremonial precedence. Yet this democratic mechanism was added onto existing structures, rather than gaining anything like paramount authority.

Hence, if the Euro-Parliament voted (say) to assume full taxative and legislative powers, to abolish the EU’s Council, and to choose the Commissioners from its own short-list, there would be an immediate crisis. Fierce objections would come not only from EU officialdom but also from the national parliaments/governments of the 28 member countries. Who really represents the people of Europe?

A notable weakness in the current arrangements is the lack of synchronisation and answerability between the national parliaments and the quasi-federal European Parliament. Were there to be a direct conflict, the sovereign states would always win. True, their parliaments are not always heeded between elections, but eventually their electorates can vote Europe’s politicians out of office. And, from time to time, they do just that. It would therefore make more sense to align the national and European Parliaments by inviting each national institution to send a politically representative cross-section of its MPs to act also as MEPs. That arrangement already governs the relationship between the 47 sovereign states in the Council of Europe (reminder: not to be confused with the EU’s two Councils) and the Council of Europe’s own Parliamentary Assembly (not to be confused with the European Parliament).9

So far, it’s been impressive how the European Union has not only held together but also expanded to the east. The fertility of ideas and the institutional inventiveness on the part of the Euro-enthusiasts has been similarly remarkable. It’s also heartening that there is still much goodwill towards the ideal of European cooperation, although it’s far from universally shared. Nonetheless, it’s time now for some fresh inventiveness – plus a willingness to abolish outmoded institutions, costs, and overlaps – to reconnect the EU with the national parliaments and their electorates. Getting the political and constitutional structures right is the best first step towards the difficult task of getting everything else right too.

1 They include (since July 2013): Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

2 They include (currently): Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain.

3 The EU also has a separate European Investment Bank, covering a wider range of countries.

4 See e.g. J.E. Stiglitz, The Euro and its Threat to the Future of Europe (2016).

5 See, for the EU’s institutions, the European Union’s own website https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions-bodies_en; and, for a severe critique of its constitution and policies, J.R. Gillingham, The EU: An Obituary (2016).

6 P.J.C., ‘Britain and Mainland Europe Viewed Long: From Concert of Europe to the Council of Europe’, BLOG/69 (Sept. 2016).

7 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/21/ventotene-summit

8 See R. Scully, Becoming European? Attitudes, Behaviour, and Socialisation in the European Parliament (2005); and many tracts urging reforms, such as P. Schmitter, How to Democratise the EU … And Why Bother? (2000).

9 See P.J.C., ‘Britain and Mainland Europe’, as above n.6.

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 70 please click here

Good-looking, debonair, raffish, sexy, attractive to both men and women, a breezy poet, a dog-lover, a radical in his politics, supporting working-class interests at home and Greek independence overseas, and a man with a title – George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), seemed almost too amazing to be true.1 But add into the mix the further pertinent facts that he was chronically impoverished; that he had a deformed foot, which gave him pain and forced him to walk with a limp; that he took to travelling restlessly overseas; that his marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke was unhappy; that many of his affairs were also tormented and short-lived; that there were accusations of incest with his half-sister and marital violence; that, as a result, Byron was considered deeply controversial by respectable society; … and his story was not straightforward.

Good-looking, debonair, raffish, sexy, attractive to both men and women, a breezy poet, a dog-lover, a radical in his politics, supporting working-class interests at home and Greek independence overseas, and a man with a title – George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824), seemed almost too amazing to be true.1 But add into the mix the further pertinent facts that he was chronically impoverished; that he had a deformed foot, which gave him pain and forced him to walk with a limp; that he took to travelling restlessly overseas; that his marriage to Anne Isabella Milbanke was unhappy; that many of his affairs were also tormented and short-lived; that there were accusations of incest with his half-sister and marital violence; that, as a result, Byron was considered deeply controversial by respectable society; … and his story was not straightforward.