MONTHLY BLOG 14, AN UNKNOWN BOOK THAT INFLUENCED ME

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2011)

Writing my father’s obituary recently, I began to muse about people who have influenced me, who emphatically include my parents. And then, in parallel, I began to think about books which had an impact on me; and decided to write about one unknown tome, which I read as a teenager.

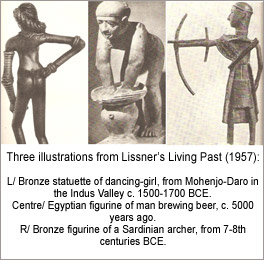

The book in question was given to me as a History prize in the sixth-form at Chislehurst and Sidcup County Grammar School for Girls (as it then was). Who chose the volume, I have no idea. I’ve never heard anyone else ever refer to it. It’s entitled The Living Past by Ivar Lissner, flowingly translated from the German by J. Maxwell Brownjohn, and published in 1957. Today the work is available via Googlebooks – and advertised among collections of rare books. The stout volume is well illustrated and mapped; and on the front cover are figures from an ancient script – encouraging the mind to fly to unknown places.

I remember reading this work with fascination as a teenager in the 1960s and then letting it lie fallow, as it was so far removed from anything in the normal History curriculum, either at school or university.

I remember reading this work with fascination as a teenager in the 1960s and then letting it lie fallow, as it was so far removed from anything in the normal History curriculum, either at school or university.

My first interest in the book, which is written with luminous ease, was triggered by its ambitious global coverage. Subtitled The Great Civilisations of Mankind, the title bears the imprint of its age. Today we know all too well just how uncivilised the behaviour of allegedly ‘civilised’ nations can be. So possibly the author would have chosen to refer to ‘cultures’ instead. But putting that niggle aside, the book starts with Mesopotamia and then tours through the archaeological/social history of: Egypt; Anatolia; Phoenicia; Persia; Palestine; India; Cambodia; China; Central Asia; Japan; Australia; Polynesia; Melanesia; North America; South America; Central America; Crete; Greece; Italy; and Carthage.

Later I noticed that most of Africa; northern Europe; and Russia were excluded. But the effect of Lissner’s light, gliding prose was such that it was easy to imagine that, with more space, he would have encompassed these other areas with equal aplomb. His text offered sweep rather than universality; and his sweep was determined to take all cultures equally seriously.

A second immediately impressive element was Lissner’s quest to make the ‘dead’ past come alive. Readers were encouraged into efforts at empathy across the generations. Many of the pithy chapters have evocative labels. ‘Cursing their Master behind his Back’ examines the nature of slavery in classical Greece, whilst the author breathes humanist sympathy for the slaves. ‘Babylon was well lit at night’ evokes the bright lights of ancient Babylon and the city’s social mores. And at the end of the Babylonian chapter, Lissner quotes moving scraps of texts from cuneiform messages, songs, and love-letters, written on clay tablets dating from thousands of years ago.

It was such personal declarations from long-dead people which, many years later, jogged my memory about Lissner’s book and got me rereading it. His impressionistic style today seems old-fashioned and I can see many points with which I would later argue. But he had influenced me and also my teaching. ‘Long-sweep’ history need not just be about assessing impersonal trends but should also incorporate the mental effort of imagining/evaluating past experiences of work, wars, loves, joys, griefs – echoing through time.

Above all, the text conveyed the implicit assumption that, with historical effort and study, one human could understand, even if not approve, the culture of any other, anywhere around the world – and at any time.

Above all, the text conveyed the implicit assumption that, with historical effort and study, one human could understand, even if not approve, the culture of any other, anywhere around the world – and at any time.

Lissner himself seems to have taken a cyclical view of history. Great ‘civilisations’ would rise and then fall (p.41). His book did not, however, follow anything like a chronological narrative. Instead, he stressed the interconnections between different cultures and the power of continuity.

Ultimately, for him, the key to ‘modernity’ was the emergence of Greek democracy. Its teachings were then conveyed to Rome, which welded ‘the spiritual order of Greece with Christianity’ (p.361). Yet Lissner’s final chapter was surprising. The book ends with ‘the tragedy of Hannibal’. Had Carthage won the Punic wars, Lissner argued, then it would have been the Carthaginians, rather than the Romans, who would have become the historic middlemen ‘between the heritage of the Mediterranean and modern Europe’. Somehow history’s flow was destined but the key actors in achieving it were not. The argument was faintly strange. But I did not worry about that upon first reading, being moved by his approach rather than his conclusions.

Long after reading the book, I discovered that Ivar Lissner (1909-67) came from a Baltic German family with Jewish ancestry but, repellently, had become an active Nazi. He joined the party in 1933 and provided military intelligence for Hitler in the Far East. Falling between several stools, he was imprisoned in harsh conditions by the Japanese from 1943-5. One would not guess any of that from the book. The international humanism seems sincere. And the chapters on Japan are affectionate. Perhaps the deep past gave him a mental escape-route from his fascist years. Certainly, the book’s tone is melancholic. It warns against praising the present at the expense of past cultures. And the nearest to explicit repentance comes in Lissner’s disparaging reference to the ‘so-called “New” Orders of our own small age’ (p.24), although that remark probably reflected anti-communism as much as anti-fascism.

Anyway, as I’ve indicated, upon first reading I was utterly uninterested in the author. Instead, I was stirred by the clarion call to study The Living Past, in the skilled translator’s effective choice of words.1 Not dead history. But a living process. The book thus acted as a ‘sleeper’ in my mind, nurturing my interest in the long-span history,2 even when it was out of fashion. Now that ‘big history’ (or cosmic history) is returning to serious attention,3 I am thoroughly glad that I was pre-primed long ago. The Living Past is a part of my own living past.

1 The German title was So Habt Ihr Geleb = literally Thus Have They Lived.

2 My contribution is Time and the Shape of History (Yale University Press, 2007).

3 The International Big History Association recruits from many disciplines, scientific as well as historical: see website www.ibhanet.org for Newsletter and call for papers at first international conference to be held in 2012.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 14 please click here