MONTHLY BLOG 126, Does classifying people in terms of their ‘Identity’ have parallels with racist thought? Answer: No; Yes; and ultimately, No.

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2021)

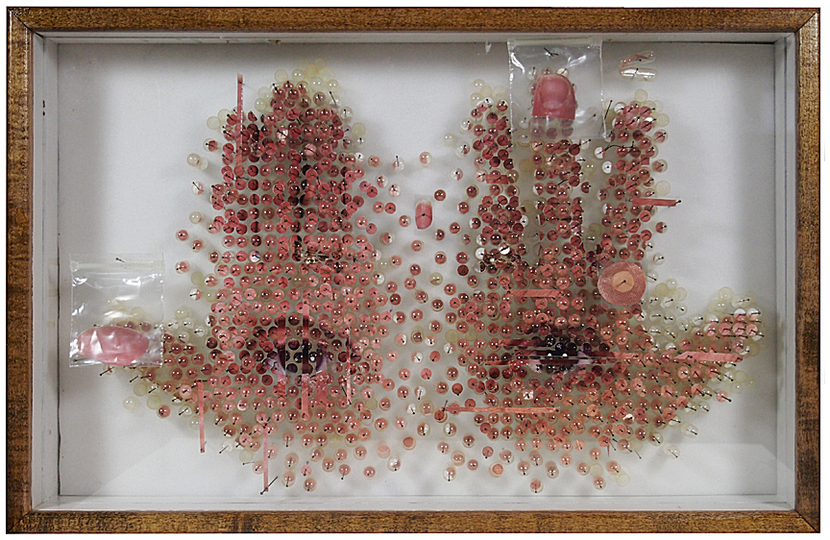

| Specimen HC1 © Michael Mapes (2013) |

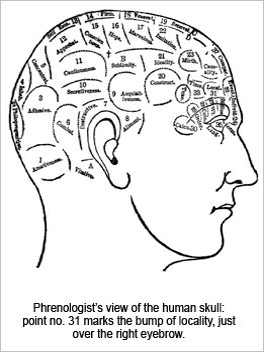

It’s impossible to think without employing some elements of generalisation. (Is it? Yes: pure mental pointillisme, cogitating in fragmentary details, would not work. Thoughts have to be organised). And summary statements about fellow human beings always entail some element of classification. (Do they? Yes, individuals are more than the sum of their bits of flesh and bones. Each one is a person, with a personality, a consciousness, a name, perhaps a national identity number – all different ways of summarising a living being). Generalisations are therefore invaluable, whilst always open to challenge.

Yet are all forms of classification the same? Is aggregative thought not only inevitable but similarly patterned, whatever the chosen criteria? Or, to take a more precise example from interpersonal relationships, does classifying a person by their own chosen ethnic identity entail the same thought processes as classifying them in terms of oppressive racial hierarchies?

Immediately the answer to the core question (are all forms of classification the same?) is No. If individuals chose to embrace an ethnic identity, that process can be strong and empowering. Instead of being labelled by others, perhaps with pejorative connotations, then people can reject an old-style racial hierarchy that places (say) one skin-colour at the top of the social heap, and another at the foot. They can simply say: ‘Yes: that is who I am; and I exult in the fact. My life – and the life of all others like me – matters.’ It is a great antidote to years of racial hatred and oppressions.

At the same time, however, there are risks in that approach. One is the obvious one, which is often noted. White supremacists can use the same formula, claiming their group superiority. And they can then campaign aggressively against all who look ‘different’ and are deemed (by them) be in ‘inferior’. In other words, oppressors can use the same appeal to the validity of group affiliation as can their victims.

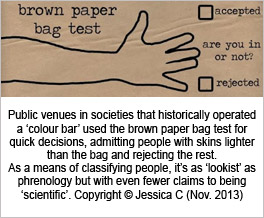

There are other difficulties too. So reverting to the core question (how similar are systems of classification?) it can be argued that: yes, assessing people by ethnic identity often turns out, in practice, to be based upon superficial judgments, founded not upon people’s actual ethnic history (often very complex) but upon their looks and, especially, their skin colours. External looks are taken as shorthand for much more. As a result, assumptions about identities can be as over-simplified as those that allocate people into separate ‘races’. Moreover, reliance upon looks can lead to hurtful situations. Sometimes individuals who believe themselves to have one particular ethnic affinity can be disconcerted by finding that others decline to accept them into one particular ‘tribe’, purely because their looks don’t approximate to required visual stereotype. For example, some who self-identify as ‘black’ are rejected as ‘not black enough’.

Finally, however, again reverting to the core question: No. Identity politics are not as socially pernicious and scientifically wrong-headed as are racial politics.1 ‘Identities’ are fluid and can be multiple. They are organised around many varied criteria: religion, politics, culture, gender, sexuality, nationality, sporting loyalties, and so forth. People have a choice as to whether they associate with any particular affinity group – and, having chosen, they can also regulate the strength of their loyalties. These things are not set in stone. Again, taking an example from biological inheritance, people with dark skins do not have to self-identify as ‘black’. They may have some other, overriding loyalty, such as to a given religion or nationality, which takes precedence in their consciousness.

But there is a more fundamental point, as well. Identities are not ideologically organised into the equivalent of racial hierarchies, whereby one group is taken as perennially ‘superior’ to another. Some individuals may believe that they and their fellows are the ‘top dogs’. And group identities can encourage tribal rivalries. But such tensions are not the same as an inflexible racial hierarchy. Instead, diverse and self-chosen ‘identities’ are a step towards rejecting old-style racism. They move society away from in-built hierarchies towards a plurality of equal roles.

It is important to be clear, however, that there is a risk that classifications of people in terms of identity might become as schematic, superficial and, at times, hurtful as are classifications in terms of so-called ‘race’. Individuals may like to choose; but society makes assumptions too.

The general moral is that classifications are unavoidable. But they always need to be checked and rechecked for plausibility. Too many exceptions at the margins suggest that the core categories are too porous to be convincing. Moreover, classification systems are not made by individuals in isolation. Communication is a social art. Society therefore joins in human classification. Which means that the process of identifying others always requires vigilance, to ensure that, while old inequalities are removed, new ones aren’t accidentally generated instead. Building human siblinghood among Planet Earth’s 7.9 billion people (the estimated 2021 head-count) is a mighty challenge but a good – and essential – one.

ENDNOTES:

1 For the huge literature on the intrinsic instability of racial classifications, see K.F. Dyer, The Biology of Racial Integration (Bristol, 1974); and A. Montagu, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race (New York, 2001 edn). It is worth noting, however, that beliefs in separate races within the one human race are highly tenacious: see also A. Saini, Superior: The Return of Race Science (2019). For further PJC meditations on these themes, see also within PJC website: Global Themes/ 4,4,1 ‘It’s Time to Update the Language of “Race”’, BLOG/36 (Dec. 2013); and 4.4.4 ‘Why is the Language of “Race” holding on for so long, when it’s Based on a Pseudo-Science?’ BLOG/ 38 (Feb. 2014).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 126 please click here

Collectively, the 15th International Congress on the Enlightenment (ICE), focusing upon Enlightenment Identities, was a huge triumph. For five days in Edinburgh in July 2019 some 2000 international participants rushed from event to event. There were not only 477 learned panel presentations and five great plenaries but also sundry conducted walks, coach tours to special venues, a grand reception, a superb concert, a pub quiz, and an evening of energetic Highland dancing. So much was happening that heads spun, and not just from the jovial Edinburgh hospitality.

Collectively, the 15th International Congress on the Enlightenment (ICE), focusing upon Enlightenment Identities, was a huge triumph. For five days in Edinburgh in July 2019 some 2000 international participants rushed from event to event. There were not only 477 learned panel presentations and five great plenaries but also sundry conducted walks, coach tours to special venues, a grand reception, a superb concert, a pub quiz, and an evening of energetic Highland dancing. So much was happening that heads spun, and not just from the jovial Edinburgh hospitality.