MONTHLY BLOG 7, WHY ARE BRITISH UNIVERSITIES POLITICALLY SO SUPINE?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2011)

I know that I am not the only person with an interest in and affection for Britain’s Universities, who is deeply worried by the Universities’ collective failure to stand up to successive central governments. Many people raise this point with me. There is a general perception that Britain’s Universities do not stand up strongly enough for the values of education – and for the supreme importance of knowledge that is not subject to tampering by political leaders. The old arms-length system of governance has already been much eroded. Ministers now talk as though Universities are agencies of the central state, instead of being independent self-governing institutions.

So why are the Universities supine vis-à-vis successive governments, whether Tory, Labour or Coalition? In reply, I generally comment, rather supinely myself: ‘Oh well, he who pays the piper calls the tune’.

Yet consider the British Army. Or the National Health Service. Both are funded by central government. But both they and their supporters among the wider public can rally formidable protests at changes which they consider undesirable. So my answer doesn’t really tackle the question.

Of course, there is never universal agreement as to which policies of successive governments are or have been detrimental to academic life. That point, however, is not my concern here. Public opinion is often divided over changes to the Army or Health Service but that has not stopped campaigns either against specific changes or in favour of other innovations. The debates over what is now called the ‘Military Covenant’ constitute one example. This traditional, if entirely unwritten, pact between the armed forces and the state may potentially be traced back to sixteenth-century levies to assist disabled solders. The term, however, is novel. It arrived in 2000, courtesy of a Ministry of Defence booklet, entitled Soldiering: The Military Covenant. And it has already become a hot political issue, with contested proposals (the Coalition currently against; Labour currently in favour) to codify the vague unwritten pact into positive law, which is likely to be costly.

By analogy, is there anything like an Educational Covenant? Or, if that’s too grand, then a general Educational Concord between the state and lifelong learners? What would it comprise? But no, education is a fragmented cause. And in the UK the Universities fall within the remit of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS). Skills! Yes, they are necessary. But what an insult to Knowledge and Learning, without which skills don’t work.

Why was there no outcry from the Universities? One answer must certainly be that the elite institutions within the tertiary sector view themselves, and are reciprocally viewed, as part of a nebulous but nonetheless discreetly powerful ‘Establishment’. That perception works against any forms of public lobbying or confrontation. Sound ‘chaps’ (both male and female) apply pressure discreetly behind the scenes.

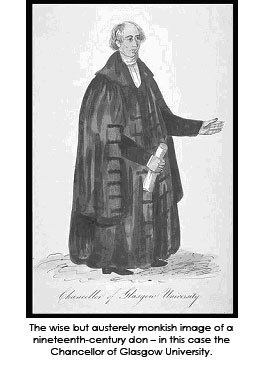

The perception applies particularly to Oxford and Cambridge. And it holds whether individual Oxbridge dons are languid establishment-types; or scatty bohemian-intellectuals; or (comparatively rare these days) earnest workerist men and women of the people; or (even rarer) zingy Morris Zapps jetting around the world from conference to conference; or (very common) harassed professionals with a preoccupied look as they continually chase behind a hundred tasks that are never done.

Behind-the scenes lobbying, however, doesn’t work nowadays – even for the elite. And it does nothing to combat out-of-date assumptions about Universities. The power of traditional assumptions is sufficiently great that Tom Sharpe’s satire of Porterhouse as a bastion of upper-class privilege, anti-intellectualism, anti-feminism, organisational incompetence, and elaborate feasting is too readily believed to be the institutional apogee to which all other tertiary institutions secretly aspire.

In fact, the reality is different in many ways. The tertiary sector is very variegated. It has faults, but they are often too neo-brutally managerialist rather than slumberingly Porterhousian.

In fact, the reality is different in many ways. The tertiary sector is very variegated. It has faults, but they are often too neo-brutally managerialist rather than slumberingly Porterhousian.

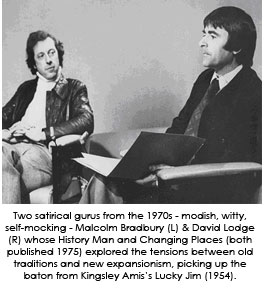

Thus a second reason for the strangled public voice of the Universities stems from the divisions within the University sector. The tactics of the old-Establishment no longer work but there is no new-Establishment consensus to make a new case. The non-Oxbridge campus novels by academics Malcolm Bradbury and David Lodge, witty and penetrating as they are, provided further satire of a sector in quest for a viable role in a doubting world.

Divisions between Universities are now institutionalised into rival lobby organisations. The Russell Group (founded 1994) represents 20 Universities, self-defined as the research elite, constituting a limited company (no: 6086902), operating from a base in Cambridge. Feeling excluded, another 19 smaller research institutions created the 1994 Group to defend their research credentials. It operates with an Executive Board, chaired by an academic, with at least five permanent staff members. A similar corporate structure services the University Alliance, which represents 23 ‘major business-focused’ Universities. And from 1997 onwards the Campaign for Mainstream Universities (CMU) has organised 27 former Polytechnics and University colleges – then known as ‘new’ Universities although many already had long histories. This group now operates as a London-based Think-tank, known as the Million+ Group. These divisions mark a classic case of self-divide and be ruled.

Divisions between Universities are now institutionalised into rival lobby organisations. The Russell Group (founded 1994) represents 20 Universities, self-defined as the research elite, constituting a limited company (no: 6086902), operating from a base in Cambridge. Feeling excluded, another 19 smaller research institutions created the 1994 Group to defend their research credentials. It operates with an Executive Board, chaired by an academic, with at least five permanent staff members. A similar corporate structure services the University Alliance, which represents 23 ‘major business-focused’ Universities. And from 1997 onwards the Campaign for Mainstream Universities (CMU) has organised 27 former Polytechnics and University colleges – then known as ‘new’ Universities although many already had long histories. This group now operates as a London-based Think-tank, known as the Million+ Group. These divisions mark a classic case of self-divide and be ruled.

Off-setting this plurality of voices and competing interests is the pan-University alliance, known as Universities UK (UUK). It began with informal meetings in the nineteenth century of a handful of Vice-Chancellors and Principals. Now it serves 133 Universities and University Colleges, together with two national sub-groups comprising Higher Education Wales and Universities Scotland. Together they seek to provide a ‘definitive’ voice for all these institutions. And they do good deeds. Recently, for example, UUK helped to pressurise the Coalition government into a partial climb-down over the conditions attached to visas for overseas students – restoring some possibilities for post-study work within the UK. Nonetheless, this umbrella organisation has a difficult task in view of the organised separatism of its constituents. UUK can campaign at the level of general policies that affect all but has to tread cautiously or not at all on issues that divide its membership.

Furthermore, there is no one governmental Department that speaks to and for the educational sector. No equivalent of the Ministry of Defence, battling for the armed forces. And without such protection, education politicians often seem to be battling against the very sector which they are supposed to be leading.

Thirdly and lastly, therefore, the Universities have an urgent job of education to do. They need to explain their intrinsic value. Higher education is not only a massive economic multiplier but it’s also an essential component of the human educational endeavour – developing and transmitting to the next generation the corpus of stored and codified human knowledge to date. The more we have of it, the better for all.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 7 please click here