MONTHLY BLOG 67, WHAT NEXT? INTERROGATING HISTORICAL EVIDENCE

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2016)

First find your evidence and check for provenance; reliability; and typicality.1 But what next? Here are three golden rules; and three research steps.

Rule One: Approach every source with a keen mixture of critical excitement. That is, embrace new evidence whilst being prepared to understand all its flaws and omissions. At all times, you need to sustain a vigorous mental debate between your research theories/hypotheses/questions/arguments – and your critical interrogation of the sources.

Rule Two: Think of the obvious ways to use any given source … and the not-so-obvious. Historical evidence can be used for many purposes, including those for which it was not originally intended. Be prepared to improvise and to think of different ways of using material.

Rule Three: Play fair with the evidence. That is, don’t use it to show things that it doesn’t show. Don’t misquote or mangle. Don’t use quotations taken out of context. And, while taking note of what the sources don’t say (as well as what they do), don’t let the practice of ‘reading the silence’ turn into an exercise of castigating the past for not being the present – or of interpolating your own issues into historic sources. Playing fair with the evidence means playing fair with research methods too. Keep a constant check to ensure that you don’t, unintentionally, pre-build your answers into your research procedures.

Then, when focusing upon a specific source or group of sources, there are three steps to consider in sequence.

Step One: understand the source’s context. This step is really important and requires work. Evidence gains meaning in the context of time and place. There are many handy guides to the different types of sources and their contexts.2 But, if none are available, researchers should investigate for themselves.

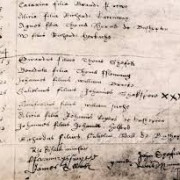

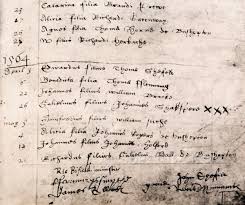

Finding a sheet of paper inscribed with five words, ‘William, son of John Shakespeare’, would not get a researcher very far. But finding them in the parish book of Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon, dated 26 April 1564, provides good evidence of the baptism of the world’s most famous William Shakespeare. [The actual source contains four words in Latin, as shown in Fig.1; and a later hand marked the entry with three crosses – a rather endearing sign of research excitement but one which would rightly attract the wrath of archivists today].

|

Fig. 1 Baptismal record of Gulielmus filius Johannis Shakspere [sic] on 26 April 1564 in Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon – entry marked in R margin by three crosses in a later hand. There is no evidence for Shakespeare’s actual birthday, but a patriotic tradition dating back to the eighteenth century ascribes it to 23 April – St George’s Day. |

Step Two: understand the source’s characteristic style (or ‘Register’, in the terminology of literary scholarship). This step entails identifying and allowing for the characteristic style of the source(s) under examination, including their strengths and weaknesses. Again, there are guides to the common characteristics of (say) different literary genres, such as autobiographies, diaries, letters. But again, where none exist, researchers should work it out for themselves.

At a very basic level, there are obvious differences in written texts between fiction and non-fiction. Poems, stories and songs are not intended to be taken literally. And within the ranks of non-fiction, there are many different types of writings, and levels of specificity. Private thoughts expressed casually, in (say) letters and diaries, do not necessarily constitute people’s final considered views. By contrast, signed and sealed legal documents may be taken as formal statements, even while the conventional legal language brings its own restrictions.

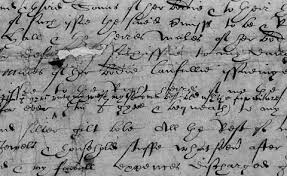

When Shakespeare bequeathed to his wife Anne Hathaway their ‘second best bed’, he was not comparing her to a summer’s day. He was leaving her a specific item of household furniture. It can be debated whether the legacy was a considered snub or a tender personal testimonial or a utilitarian disposal of family assets or a casual after-thought.3 But the terse legal language expresses absolutely nothing about motivation.

|

Fig.2: Extract from p. 3 of Shakespeare’s will dated March 1616, penned by a lawyer but signed by William Shakespeare. (from original in Probate Registry, Somerset House, London). The bequest I gyve vnto my wife my second best bed with the furniture, is contained in the interpolated line of text (seventh from top), indicating that it was a late addition, made after the first draft, and hence inserted very shortly before Shakespeare’s death in April 1616. |

Step 3: after assessing both context and register, it’s time to savour in full the contents of any given source or set of sources. That includes every last detail. In a written text, it’s essential to study the choice of language, as well as its content(s) and meaning(s). As my former research supervisor Jack Fisher used to say: squeeze every last drop of juice from the lemon.

Moreover, while it’s wrong to read too much cosmic meaning into every passing fragment of evidence, it’s always worth remembering that some information will turn out to be more telling than others. Keep an eye open for sources which have a significance beyond their immediate remit. (Sometimes that becomes apparent only upon later reflection, sending the researcher scurrying back to the source material for a fresh appraisal.)

The possibilities are bounded by the availability of evidence. We cannot rediscover everything about the past. So, without fresh finds, it is unlikely that researchers will ever know Shakespeare’s actual date of birth. Nonetheless, the multiplication effect of multiple sources, multiple methodologies, and endless research ideas/debates, in the context of changing perspectives over time, means that historical understanding is always expanding and always being tested. The critical assessment of bounded evidence is the launching pad for unbounded knowledge. ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio …’

1 This BLOG is the pair to BLOG/ 66 (June 2016) and is equally dedicated to all past students on the Core Course of Royal Holloway (London University)’s MA in Modern History: Power, Culture, Society.

2 For a super-exemplary analysis of sources and their context, see The Proceedings of the Old Bailey: London’s Central Criminal Court, 1674-1913 on-line, co-directed by Tim Hitchcock and Robert Shoemaker: www.oldbaileyonline.org.

3 See J. Rogers, The Second Best Bed: Shakespeare’s Will in a New Light (Westport, Conn., 1993); M.S. Hedges, The Second Best Bed: In Search of Anne Hathaway (Lewes, 2000); G. Greer, Shakespeare’s Wife (2007); and BBC report www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/what-will-s-will-tells-us-about-shakespeare (2016).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 67 please click here