If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2015)

Supporting the losing party in a general election campaign is not fun.1 But it does provide space for fresh thoughts. Mine are as follows.2 The Labour Party needs to update its name. It is now over one hundred years old. Its name is historic but not sacrosanct. The term ‘Labour’ has some excellent qualities: it evokes good honest toil (‘the labourer is worthy of his hire’), as opposed to idle feckless sponging. But as a socio-political marker, it doesn’t match the realities of life in Britain today.

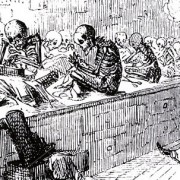

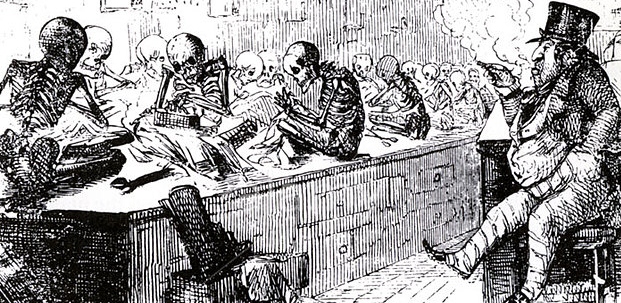

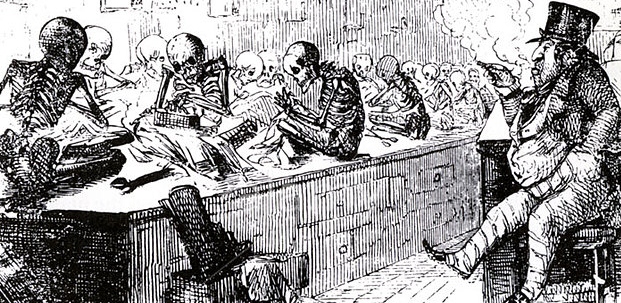

The original name for ‘Labour’ sprang from an old binary division between ‘Capital’ and ‘Labour’. It worked well in a northern industrial mill town like (say) Preston.3 There, a few big capitalist bosses employed a massive industrial workforce of manual workers. Hence it was not unreasonable for the workers to view their interests as structurally different from those of their employers (even if in certain circumstances the two sides might share a common interest in keeping the industry afloat). The same division might also apply in smaller workshops too, where wages were kept particularly low. So the following Victorian cartoon of a clothing sweat-shop (illus.1) highlighted the murderous gulf between uncaring Capital and sweated Labour.

BDFH6R VICTORIAN FACTORY – Cartoon satirising the sweat-shops where clothing was mass produced in conditions of great hardship.

Illustration 1: satire of a Victorian Sweat-Shop, with an unmissable message.

Copyright © Pictorial Press Ltd |

But, from the start, the model of a few big exploitative bosses versus many exploited workers did not apply in all circumstances. There were areas, like the Birmingham metalware district, where small and medium-sized workshops prevailed.4 Masters and men were much closer in their working relationships; and there was much more movement up and down the industrial ladder. And in all circumstances, there were enlightened employers, as well as exploitative ones.

As a result, the stark Labour/Capital divide was a myth as a universal state of affairs. Or, rather, it was a partial reality, generalised to stand proxy for a variegated whole.

Today, a deep binary chasm is even less convincing as an expression of how the entire British economy works. Neither ‘Capital’ nor ‘Labour’ has a pristine separateness. In practice, they are muddled and overlapping, just as class divisions are comparatively fuzzy today. Capital and Labour do appear in formal models of the economy as two fundamental resources;5 but such abstractions do not automatically map onto the day-to-day economic activity of individuals.

Take Capital: lots of people today have capital assets, whether in the form of real property or investments. They include most of the professional and commercial middle class and a number of manual workers from the working class, particularly those who purchased their former Council homes.6 Indeed, the extension of home ownership was precisely viewed by the Conservative Party as a strategy to blur any notional Capital/Labour divide. In practice, the right-to-buy policy is not quite working as the Conservatives envisaged. Growing numbers of former Council houses are being purchased on the open market, in the context of today’s acute housing shortage, and being converted back into properties for rent, only this time organised by private letting empires.7

Nonetheless, the general point holds good. Owners of capital in property and investments include not just big businessmen and the ‘idle rich’ who live on investment income – but also a huge swathe of people (both working and retired), including most of the middle-class and a section from working-class backgrounds.

Or take Labour: lots of people work hard for their living but are not sociologically classified as manual workers. People from middle-class occupations, whether commercial or professional, are workers who do not define themselves across-the-board as Labour. Most don’t, chiefly because they also own Capital.

It’s true that, historically and still currently, significant numbers of middle-class professionals do broadly identify with the Labour Party, especially if they come from the liberal professions (teachers, doctors, some lawyers). The early Labour Party tried to accommodate these activists into the Labour/Capital divide by classifying the Labour membership in Clause 4 as ‘workers by hand or by brain’. But that is not a very happy distinction. ‘Workers by hand’ could be taken to imply, condescendingly, that manual workers don’t really think. And ‘workers by brain’ doesn’t really appeal as a self-definition across the large and amorphous middle class. For example, plenty of shopkeepers do think but wouldn’t define themselves as ‘brainworkers’.

Anyway, it’s not just the middle classes who don’t identify with Labour as a social category. As a literal label, it has many other blank areas. It does not cover substantial swathes of the non-working population (the retired; the out-of-work); or the intermittently employed (casual workers); or the non-gainfully employed (interns).

Remember that, in 2011, only 9% of the workforce in England and Wales was employed in the manufacturing sector (down from 36% in 1841).8 That figure included many in large factories (some harmonious, some confrontational) but also many in small intimate workshops, where cooperation is stressed.

And remember too that, in 2011, a massive majority of the workforce – 81% (up from 33% in 1841) – was engaged in the service sector. That contains a great variety of occupations and workplace situations. It also employs 92% of all women in work. Many service industry jobs are specifically organised around a principle of cooperation and conciliation. Where they provide commercial services, the mantra has it that clients are ‘always right’ (even if they aren’t). As a result, the service sector favours an ethos of caring ‘service’ rather than one of binary conflict.

Furthermore, another fast-growing group today straddles the Capital/Labour divide by definition. These are the self-employed. They are simultaneously their own boss and their own workforce. Either way, these people again are not unambiguously Labour, even though many work very hard and often struggle.

So the name of Labour is tricky for a political party seeking a democratic majority. It alienates many of the middle classes. It doesn’t talk meaningfully to the self-employed. And it is not even a clear identifier for all the working class. But Labour’s language still pretends that factory workers are the norm. The problems within this terminology probably accounts for the subliminal note of unease in the speeches of the predominantly middle-class activists among the Labour leadership. They sound as though they are not sure whom they are addressing – and on whose behalf they are speaking. In the 2015 election campaign, ‘hard-working families’ was used to give Labour a human embodiment. Yet, since the phrase appeared to exclude all single people, childless couples, unemployed people, and pensioners, it didn’t really help.

These points are not intended to deny that plenty of things are very wrong in today’s society. They are. Economic exploitation has not disappeared. And new problems have emerged. In a world where Labour and Capital are interlocked, there’s a massively good case for promoting greater equality and social cooperation.9 Everyone will benefit from that. But today’s task can only be done by using today’s language. Labour needs a name which embraces all the people.10

1 See PJC, ‘Post-Election Special: On Losing?’ Monthly BLOG/54 (June 2015).

2 Personal: I was reared in a Labour household; cut my political teeth as a Labour canvasser in my mid-teens; was a Labour Councillor in my late 20s; have held many local Labour Party posts; currently, one of organisers of Battersea Labour Party; and don’t intend to stop.

3 The urban model for Charles Dickens’s Coketown in his Hard Times (1854).

4 See e.g. D. Smith, Conflict and Compromise: Class Formation in English Society, 1830-1914 – A Comparative Study of Birmingham and Sheffield (1982).

5 Classic resources for economic production are capital; land; and labour; to which a fourth factor of entrepreneurship is sometimes added.

6 Future research will show what percentage of former tenants who purchased Council properties at a discount remained as property-owners over the long term (whether retaining the original properties or trading up) and what percentage sold their properties and exited the property market. For accusations that some poor tenants are being fraudulently ‘gifted’ with funds to purchase their properties at a discount and then to sell on immediately to private speculators, see Claire Ellicott report in Daily Mail online, 12 Jan. 2015.

7 As reported in many newspapers and trade journals – e.g. ‘Right to Buy turns Ex-Council Homes into Buy-to-Let Goldmine’, Letting Agent Today (24 July 2012); ‘Private Landlords Cash in on Right to Buy’, The Observer (12 July 2014).

8 All statistics from Britain’s Office of National Statistics, based upon 2011 census returns for England and Wales: see http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/census/2011-census-analysis/170-years-of-industry/170-years-of-industrial-changeponent.html

9 R. Wilkinson and K. Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always do Better (2009); A.B. Atkinson, Inequality: What Can be Done? (Cambridge, Mass., 2015).

10 Institutional inertia makes change difficult but I believe that a new name or a modification of Labour’s old name (not New Labour!) can emerge from debates within the movement.

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 55 please click here

Call it a political RED-GREEN alliance. Call it a loose political RED-GREEN federation. Even a move towards a full-blown RED-GREEN party merger? But enough shilly-shallying. It’s time for action.

Call it a political RED-GREEN alliance. Call it a loose political RED-GREEN federation. Even a move towards a full-blown RED-GREEN party merger? But enough shilly-shallying. It’s time for action.