MONTHLY BLOG 56, MORE POST-ELECTION MEDITATIONS: ON CHANGING THE LABOUR PARTY’S NAME

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2015)

Raising questions about the name of a proud political party with over a century of history behind it makes one appreciate all over again the force of continuity (or it can also be called inertia) in history.1 That’s because most people, when invited to consider whether Britain’s Labour Party is rightly named,2 just stare in surprise. That response comes particularly strongly from the cadres of committed party members, but also from individuals among the wider public as well.

After all, ‘Labour’ is a well established brand name. It can obviously be argued therefore that it’s folly to shed a known moniker in favour of the unknown. There are plenty of examples of commercial rebrandings which have flopped disastrously. Just Google on that topic. Some companies have even rebranded and then had to reverse the rebranding when faced with howls of public rejection.3

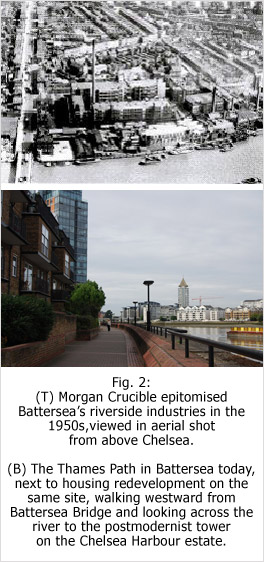

It must also be admitted that earlier suggestions of different names for the Labour Party don’t have a great track record. For example, I was interested to learn that in 1959 Douglas Jay, Battersea’s long-serving MP from 1946 to 1983, had proposed the ‘Reform Party’ as a moderate alternative.4 It seems to have been an isolated suggestion. And, at any rate, it was met with a resounding silence.

As a name, ‘Reform’ had a certain period, even Whiggish, charm. It was predicated on the assumption that Labour was the party of change and the Conservatives the party of resistance to change. But that’s too simplistic. According to circumstances, it can be the Conservatives who propose innovations (as now in the Cameron government’s expressed desire to shrink the state) while assorted groups on the Left campaign to prevent specific changes (as in campaigns to Stop this! or to Save that!).

For Labour, a truly serious crisis of identity occurred in 1981. The so-called Gang of Four and their supporters seceded to found the new Social Democratic Party. Their chosen name remains a well-known one across continental Europe for the parliamentary Left.5 But in Britain, after the initial flurry, their cause and their nomenclature didn’t resonate with the electorate.6 In 1988 the majority of the SDP merged with the Liberals. The new joint force was initially named as ‘Social and Liberal Democrats’, to be summarised as ‘Democrats’ – in a nod this time to American political nomenclature. But their own members strenuously objected. So in 1989 they adopted instead the compromise ‘Liberal Democrats’, generating a political force which has since then boomed and now (2015) fallen into disarray.

There are several morals from these case-histories. One is that changing a party’s name may bring initial success but can’t automatically be relied upon to last. (That point is obvious but worth stating). Another is that changing nomenclature is an emotional and politically freighted task, which, if ’twere done, ’twere best done by incremental adaptation, emerging from broad discussion. That’s why it’s equally obvious that, whatever individuals may or may not propose, successful innovations will emerge and survive within political movements as a whole, in the wider context of the changing political scene.

Certainly it was his policy of adaptive gradualism which gave Tony Blair an initial success with ‘New Labour’. The mantra began as a conference slogan in 1994. It was then promoted into a positive manifesto in 1996, offering New Labour: New Life for Britain. The revised name cleverly linked continuity with the fresh appeal of novelty and a modified political agenda.7 Had it not been for the unsuccessful aftermath of the Anglo-American-allied invasion of Iraq in March 2003 (without having declared war), the terminology might still be alive and kicking. Yet today it has lost clarity of meaning and thus credibility – and is hardly used, even within the Labour Party.

Why then is it worth reconsidering the question of names? Some activists within the Labour movement have reproved me. They argue that the important thing is to campaign first – and then think about political branding afterwards. But in my view the two are the same. Campaigning without a clear message is nearly as bad as renaming a party in a campaign vacuum.

Today, there’s plenty of scope for a rethink on the Left – that is, not just within the Labour Party. Lots of people are expressing interest, in conversations and in the press. Personally, I’d like to see a political alliance, if not a formal merger, between Labour plus the Greens, the Liberal Democrats, and left-wingers in the Scottish and Welsh Nats. It might not be called a Popular Front but that’s what it would be.

But, whether that ever happens or not, it’s still useful for Labour to rethink its name and mission. It’s not clear today who or what it stands for. One commentator, from the cultural Left, had recently dubbed Labour’s name as ‘a great grey millstone’ around the party’s neck, with the clear implication that it is impeding a fundamental rethink.8

Not only is the term socially partial rather than inclusive – but it’s not even clear precisely which part of British society it’s supposed to embrace. And, to make things electorally even worse, whichever sections of voters are intended to be the chief beneficiaries of Labour’s policies, they generally don’t vote for Labour in sufficient numbers to make the positives of the name outweigh the negatives.

Indeed, paradoxically, some senior Conservatives are today toying with claiming themselves to be the ‘workers’ party’,9 trying to ensure that Labour gets stuck with the implication of constituting the ‘shirkers’ party’, just supporting those on benefits. Of course, such a dichotomy is wildly over-simplified. Many people receiving state benefits are actually in work; many others, who receive financial aid from the state (eg. in the form of mortgage relief or tax relief on ISAs) don’t consider their own arrangement as ‘benefits’.

Sometimes, however, some leading Labour politicians appear to talk as though they see their role chiefly as constituting last-resort helpers of all of society’s failures and losers. Such an assumption is not only rather patronising – but it is seriously misleading, as well as electorally unappealing, even to the traditional working class, let alone to the self-employed and to swathes of the middle class.

Labour needs a much better name to express its progressive commitment to creating a fairer, freer, more egalitarian, more socially cohesive, more culturally inclusive, more tolerant, healthier, happier, and more ambitious Britain – for all the people, including the young. It may be a new name or a compound of the old name with a new adjective. I have heard various thoughts – Progressives? Progressive Labour? People’s Party? – but it’s for everyone to decide.

So I predict that a new or amended name/campaign will emerge within the broad Labour movement – or else the electorate will make the decision for Labour by choosing other parties. What’s in a name? As always: Plenty!

| Could it be Labour’s Rose by an amended Name? |

1 See PJC, ‘Why is the Formidable Power of Continuity so often Overlooked?’ BLOG/2 (Nov. 2010).

2 See PJC, Post-Election Meditations: Should the Labour Party Change its Name?’ BLOG/55 (July 2015).

3 See e.g. Mallory Russell, Business Insider (March 2012): http://www.businessinsider.com/14-brands-that-had-to-reverse-their-horrible-attempts-at-rebranding.

4 Ex inf. Mary Jay, Douglas Jay’s widow, with thanks for this reference.

5 This historic name appears on the Labour Party’s website but is hardly ever used. For the wider history of Europe’s Social Democratic parties, many now facing electoral problems, see C. Pierson, Hard Choices: Social Democracy in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge, 2001).

6 I.M. Crewe and A.S. King, SDP: The Birth, Life and Death of the Social Democratic Party (Oxford, 1995).

7 See F. Faucher-King and P. Le Galès, The New Labour Experiment: Change and Reform under Blair and Brown, transl. G. Elliott (Stanford, CA., 2010).

8 John Harris, ‘Who Should Labour Speak for Now?’ The Guardian, 13 July 2015, p. 23.

9 New Conservative deputy chairman MP Rob Halfon interviewed in The Sun, 18 May 2015.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 56 please click here

As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration.

As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration. Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

Of course, Karr was not completely right. Changes undoubtedly do happen, both gradually and dramatically. But they are always tempered by the power of Continuity. In fact, innovations may fail or prove to be counterproductive – either because opponents consciously strive to circumvent change – or because the innovations are imperfectly planned and/or implemented – or because the innovations have anyway little intrinsic chance of success.

Of course, Karr was not completely right. Changes undoubtedly do happen, both gradually and dramatically. But they are always tempered by the power of Continuity. In fact, innovations may fail or prove to be counterproductive – either because opponents consciously strive to circumvent change – or because the innovations are imperfectly planned and/or implemented – or because the innovations have anyway little intrinsic chance of success.