MONTHLY BLOG 147, A Great Painted Tribute to an Eighteenth-Century Cultural Ambassador between Global East & West

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2023)

| Image 1: Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Omai (c.1776) This cultural ambassador to Britain from the other side of the world is shown in ‘exotic’ robes and with bare feet – but his pose is open and friendly, and his gaze (said to be a good likeness) is candid |

As British sailors and explorers increasingly travelled the world in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,1 so the public back home clamoured to read all about it. Fictional fantasias like Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719) and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) became instant best-sellers. And factual accounts were eagerly consulted too.

In 1703, London society was enthused by the presence of a strange traveller, purporting to have arrived from Formosa (today’s Taiwan).2 He had exotic habits; and recounted tall tales about life in the orient. His Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa (1704) had a huge success – and was quickly translated into German and French. The book included details of the Formosan language; and provided a Formosan translation of the Lord’s Prayer.

Alas, however, it was all invented nonsense. The author turned out to be a mendacious Frenchman, named George Psalmanazar (c.1679-1763). His imposture was soon discovered; and his fame collapsed. Oddly, however, the man himself did not disappear, shamefaced. He continued to live in London as a jobbing writer, and later repented his Formosan hoax. Psalmanazar’s brief surge to fame had, however, undeniably shown that there was great public curiosity to learn about the wider world.

Another exotic visitor reached Britain in the 1770s. But this youthful Polynesian newcomer was the real thing. Omai (c.1751-c.1779), also known as Mai in his own language, was a cultural ambassador, bearing witness to his own people’s distinctive way-of-life.3 In personality, he was gracious, charming and amusing. And he was also willing to learn, managing after a while to speak good English, with his own accent.

Omai had arrived in 1774, on one of the ships returning from Captain Cook’s second voyage of discovery in the Pacific; and was greeted with immense excitement. He socialised with many luminaries, including King George III, Dr Samuel ‘Dictionary’ Johnson, the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks, and the novelist Fanny Burney. All who met Omai could observe differences of race, language, culture and clothing – as well as their shared humanity.4

The eminent artist Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-92) painted Omai as a princely visitor, majestic yet with his feet well and truly on the ground. He was no threat; no monster; no fiction.

Eventually, Omai returned to the island of Tahiti with Captain Cook (1728-79), when the great explorer made his third voyage to the Pacific – a voyage that took Cook on to discoveries, misunderstandings, quarrels and his own death in Hawaii.5 Reflecting upon the impact of the Tahitian traveller, the playwright John O’Keefe sought to dramatise the case for peaceful co-existence. In the pantomime, Omai, the heir to the throne of Tahiti, is due to marry Londina, the daughter of Britannia. Yet they struggle against many obstacles. The play helped to gild the reputations of both Cook and Omai. However, by the time that Omai: Or, a Trip Round the World was first performed in 1785, the real-life hero had died young in Tahiti.

Given that global encounters throughout the eighteenth century were very often marred by misunderstandings and conflicts, Omai’s peaceful embassy was a model for the constructive exchange of global knowledge. He did not do amazing things. Nor did he write his memoirs (shame!). Instead, he was a living cultural ambassador, whose message is as relevant today as it was then.

Today there is a campaign to save the Portrait of Omai for the nation.6 If successful, the painting will be sent on tour in Britain and possibly also at some future date to Tahiti, to continue the mutual cultural exchange that the real man himself undertook. Would Omai, Captain Cook, and Joshua Reynolds (to name but three eminent Georgians) have approved? They certainly would. They valued shared global knowledge; and so must we.

|

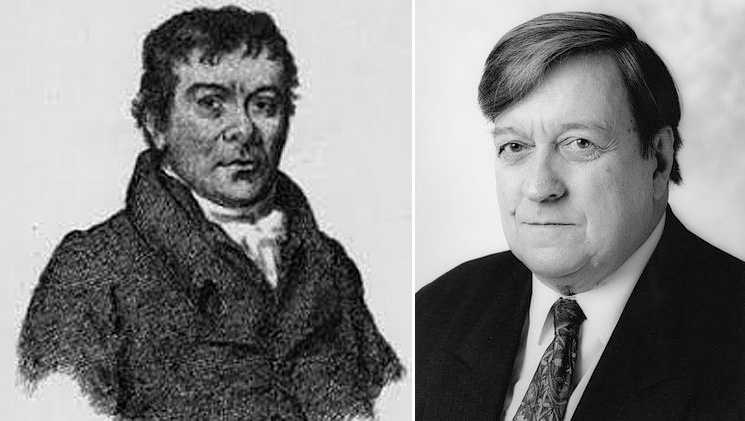

Images 2 and 3: Details from separate portraits of Omai and of James Cook, |

ENDNOTES:

1 P.J. Corfield, The Georgians: The Deeds and Misdeeds of Eighteenth-Century Britain (London, 2022), pp. 20-40.

2 M. Keevak, The Pretended Asian: George Psalmanazar’s Eighteenth-Century Formosan Hoax (Detroit, Michigan, 2004).

3 G. Rendle-Short (ed.), Cook and Omai: The Cult of the South Seas (Canberra, 2001); R.M. Connaughton, Omai: The Prince who Never Was (London, 2005).

4 L.H. Zerne, ‘“Having a Lesson of Attention from Omai”: Frances Burney, Omai the Tahitian, and Eighteenth-Century British Constructions of Racial Difference’, Burney Journal, 10 (2010), pp. 87-104.

5 G. Williams, The Death of Captain Cook: A Hero Made and Unmade (London, 2008); N. Thomas, Discoveries: The Voyages of Captain Cook (London, 2018).

6 J. Gapper, ‘Joshua Reynolds’ “Painting of Omai” is a National Treasure. Why Are We Struggling to Save It’? Financial Times, 23 Feb. 2023 https://www.ft.com/content/bfa30b2c-b1bc-446a-89ad-03b558f37ba5 (consulted 24-4-2023). For information on the appeal, see artfund.org/donate.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 147 please click here