MONTHLY BLOG 74, WHY CAN’T WE THINK ABOUT SPACE WITHOUT TIME?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2017)

Well, why not? Why can’t we think about Space without Time? It’s been tried before. A persistent, though small, minority of philosophers and physicists deny the ‘reality’ of Time.1 True, they have not yet made much headway in winning the arguments. But it’s an intriguing challenge.

Space is so manifestly here and now. Look around at people, buildings, trees, clouds, the sun, the sky, the stars … And, after all what is Time? There is no agreed definition from physicists. No simple (or even complex) formula to announce that T = whatever? Why can’t we just banish it? Think of the advantages. No Time … so no hurry to finish an essay to a temporal deadline which does not ‘really’ exist. No Time … so no need to worry about getting older as the years unfold in a temporal sequence which isn’t ‘really’ happening. In the 1980s and 1990s – a time of intellectual doubt in some Western left-leaning philosophical circles – a determined onslaught upon the concept of Time was attempted by Jacques Derrida (1930-2004). He became the high-priest of temporal rejectionism. His cause could be registered somewhere under the postmodernist banner, since postmodernist thought was very hostile to the idea of history as a subject of study. It viewed it as endlessly malleable and subjective. That attitude was close to Derrida’s attitude to temporality, although not all postmodernist thinkers endorsed Derrida’s theories.2 His brand of ultra-subjective linguistic analysis, termed ‘Deconstruction’, sounded, as dramatist Yasmina Reza jokes in Art, as though it was a tough technique straight out of an engineering manual.3 In fact, it allowed for an endless play of subjective meanings.

For Derrida, Time was/is a purely ‘metaphysical’ concept – and he clearly did not intend that description as a compliment. Instead, he evoked an atemporal spatiality, named khōra (borrowing a term from Plato). This timeless state, which pervades the cosmos, is supposed to act both as a receptor and as a germinator of meanings. It is an eternal Present, into which all apparent temporality is absorbed.4 Any interim thoughts or feelings about Time on the part of humans would relate purely to a subjective illusion. Its meanings would, of course, have validity for them, but not necessarily for others.

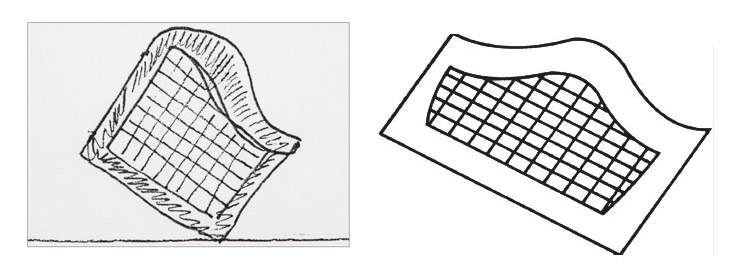

So how should we think of this all-encompassing khōra? What would Space be like without Time? When asked in 1986, Derrida boldly sketched an image of khōra as a sort of sieve-like receptacle (see Fig.1).5 It was physical and tangible. Yet it was also intended to be fluid and open. Thus the receptacle would simultaneously catch, make and filter all the meanings of the world. The following extract from an explanatory letter by Derrida by no means recounts the full complexity of Derrida’s concept but gives some of the flavour:6

I propose then […] a gilded metallic object (there is gold in the passage from [Plato’s] Timaeus7 on the khōra […]), to be planted obliquely in the earth. Neither vertical, nor horizontal, a extremely solid frame that would resemble at once a web, a sieve, or a grill (grid) and a stringed musical instrument (piano, harp, lyre?): strings, stringed instrument, vocal chord, etc. As a grill, grid, etc., it would have a certain relationship with the filter (a telescope, or a photographic acid bath, or a machine, which has fallen from the sky, having photographed or X-rayed – filtered – an aerial view). …

|

Fig. 1 (L) Derrida’s 1986 sketch of Spatiality without Time, also (R) rendered more schematically |

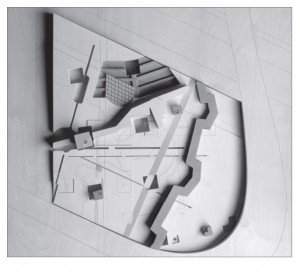

In 1987, the cerebral American architect Peter Eisenman (1932- ), whose stark works are often described as ‘deconstructive’, launched into dialogue with Derrida. They discussed giving architectural specificity to Derrida’s khōra in a public garden in Paris.8 One cannot but admire Eisenman’s daring, given the nebulousness of the key concept. Anyway, the plan (see Fig. 2) was not realised. Perhaps there was, after all, something too metaphysical in Derrida’s own vision. Moreover, the installation, if erected, would have soon shown signs of ageing: losing its gilt, weathering, acquiring moss as well as perhaps graffiti – in other words, exhibiting the handiwork of the allegedly banished Time.

|

Fig.2 Model of Choral Works by Peter Eisenman |

So the saga took seriously the idea of banishing Time but couldn’t do it. The very words, which Derrida enjoyed deconstructing into fragmentary components, can surely convey multiple potential messages. Yet they do so in consecutive sequences, whether spoke or written, which unfold their meanings concurrently through Time.

In fact, ever since Einstein’s conceptual break-through with his theories of Relativity, we should be thinking about Time and Space as integrally linked in one continuum. Hermann Minkowski, Einstein’s intellectual ally and former tutor, made that clear: ‘Henceforth Space by itself, and Time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality’.9 In practice, it’s taken the world one hundred years post-Einstein to internalise the view that propositions about Time refer to Space and vice versa. Thus had Derrida managed to abolish temporality, he would have abolished spatiality along with it. It also means that scientists should not be seeking a formula for Time alone but rather for Space-Time: S-T = whatever?

Lastly, if we do want a physical monument to either Space or Time, there’s no need for a special trip to Paris. We need only look around us. The unfolding Space-Time, in which we all live, looks exactly like the entire cosmos, or, in a detailed segment of the whole, like our local home: Planet Earth.

|

Fig.3 View of Planet Earth from Space |

1 For anti-Time, see J. Barbour, The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Our Understanding of the Universe (1999), esp. pp. 324-5. And the reverse in R. Healey, ‘Can Physics Coherently Deny the Reality of Time?’ in C. Callender (ed.), Time, Reality and Experience (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 293-316.

2 B. Stocker, Derrida on Deconstruction (2006); A. Weiner and S.M. Wortham (eds), Encountering Derrida: Legacies and Futures of Deconstruction (2007).

3 Line of dialogue from play by Y. Reza, Art (1994).

4 D. Wood, The Deconstruction of Time (Evanstown, Ill., 2001), pp. 260-1, 269, 270-3; J. Hodge, Derrida on Time (2007); pp. ix-x, 196-203, 205-6, 213-14.

5 R. Wilken, ‘Diagrammatology’, Electronic Book Review, 2007-05-09 (2007): http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/electropoetics/intermingled

6 Letter from Derrida to Peter Eisenman, 30 May 1986, as cited in N. Leach (ed.), Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory (1997), pp. 342-3. See also for formal diagram based on Derrida’s sketch, G. Bennington and J. Derrida, Jacques Derrida (1993), p. 406.

7 A.E. Taylor, A Commentary of Plato’s Timaeus (Oxford, 1928).

8 J. Derrida and P. Eisenman, Chora L Works, ed. J. Kipnis and T. Leeser (New York, 19997).

9 Cited in P.J. Corfield, Time and the Shape of History (2007), p. 9.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 74 please click here