MONTHLY BLOG 65, HOW DID WOMEN FIRST MANAGE TO BREAK THE GRIP OF TRADITIONAL PATRIARCHY?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2016)

Talking of taking a long time, it took centuries for women to break the grip of traditional patriarchies. How did women manage it? In a nutshell, the historical answer was (is) that literacy was the key, education the long-term provider, and the power of persuasion by both men and women which slowly turned the key.

But let’s step back for a moment to consider why the campaign was a slow one. The answer was that it was combating profound cultural traditions. There was not one single model for the rule of men. Instead, there were countless variants of male predominance which were taken absolutely for granted. The relative subordination of women seemed to be firmly established by history, economics, family relationships, biology, theology, and state power. How to break through such a combination?

The first answer, historically, was not by attacking men. That was both bad tactics and bad ideology. It raised men’s hackles, lost support for the women’s cause, and drove a wedge between fellow-humans. Thus, while there has been (is still) much male misogyny or entrenched prejudice against women, any rival strand of female misandry or systematic hostility to men has always been much weaker as a cultural tradition. It lacks the force of affronted majesty which is still expressed in contemporary misogyny, as in anonymous comments on social media.

Certainly, for many ‘lords of creation’, who espoused traditional views, the first counter-claims on behalf of women came as a deep shock. The immediate reaction was incredulous laughter. Women who spoke out on behalf of women’s rights were caricatured as bitter, frustrated old maids. A further male response was to conjure up images of the ‘vagina dentata’ – the toothed vagina of mythology. It hinted at fear of sex and/or castration anxiety. And it certainly dashed women from any maternal pedestal: their nurturing breasts being negatived by the biting fanny.

| Pablo Picasso, Femme (1930). |

Accordingly, one hostile male counter-attack was to denounce feminists as no more than envious man-haters. If feminists then resisted that identification, they were pushed onto the defensive. And any denials were taken as further proof of their cunningly hidden hostility.

Historically, however, the campaigns for women’s rights were rarely presented as anti-men in intention or actuality. After all, a considerable number of men were feminists from the start, just as a certain proportion of women, as well as men, were opposed. Such complications can be seen in the suffrage campaigns in the later Victorian period. Active alongside leading suffragettes were men like George Lansbury, who in 1912 resigned as Labour MP for Bow & Bromley, to stand in a by-election on a platform of votes for women. (He lost to an opponent whose slogan was ‘No Petticoat Government’.)

Meanwhile, prominent among the opponents of the suffragettes were ladies like the educational reformer Mary Augusta Ward, who wrote novels under her married name as Mrs Humphry Ward.1 She chaired the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League (1908-10), before it amalgamated with the Men’s National League. Yet Ward did at least consider that local government was not beyond the scope of female participation.

Such intricate cross-currents explain why the process of change was historically slow and uneven. Women in fact glided into public view, initially under the radar, through the mechanism of female literacy and then through women’s writings. In the late sixteenth century, English girls first began to take up their pens in some numbers. In well-to-do households, they learned from their brothers’ tutors or from their fathers. Protestant teachings particularly favoured the spread of basic literacy, so that true Christians could read and study the Bible, which had just been translated into the vernacular Indeed, as Eales notes, the wives and daughters of clergymen were amongst England’s first cohorts of literary ladies.2 Their achievements were not seen as revolutionary (except in the eyes of a few nervous conservatives). Education, it was believed, would make these women better wives and mothers, as well as better Christians. They were not campaigning for the vote. But they were exercising their God-given brainpower.

|

Young ladies in an eighteenth-century library, being instructed by a demure governess, under a bust of Sappho – a legendary symbol of female literary creativity. |

As time elapsed, however, the diffusion of female literacy proved to be the thin end of a large wedge. Girls did indeed have brainpower – in some cases exceeding that of their brothers. Why therefore should they not have access to regular education? Given that the value of Reason was becoming ever more culturally and philosophically stressed, it seemed wise for society to utilise all its resources. That indeed was the punchiest argument later used by the feminist John Stuart Mill in his celebrated essay on The Subjection of Women (1869). Fully educating the female half of the population would have the effect, he explained, of ‘doubling the mass of mental faculties available for the higher service of humanity’. Not only society collectively but also women and men individually would gain immeasurably by accessing fresh intellectual capital.3

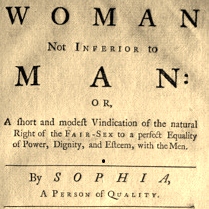

Practical reasoning had already become appreciated at the level of the household. Throughout the eighteenth century, more and more young women were being instructed in basic literacy skills.4 These were useful as well as polite accomplishments. One anonymous text in 1739, in the name of ‘Sophia’ [the spirit of Reason], coolly drew some logical conclusions. In an urbanising and commercialising society, work was decreasingly dependent upon brute force – and increasingly reliant upon brainpower. Hence there was/is no reason why women, with the power of Reason, should not contribute alongside men. Why should there not be female lawyers, judges, doctors, scientists, University teachers, Mayors, magistrates, politicians – or even army generals and admirals?5 After all, physical strength had long ceased to be the prime qualification for military leadership. Indeed, mere force conferred no basis for either moral or political superiority. ‘Otherwise brutes would deserve pre-eminence’.6

There was no inevitable chain of historical progression. But, once women took up the pen, there slowly followed successive campaigns for female education, female access to the professions, female access to the franchise, female access to boardrooms, as well as (still continuing) full female participation in government, and (on the horizon) access the highest echelons of the churches and armed forces. In the very long run, the thin wedge is working. Nonetheless, it remains wise for feminists of all stripes to argue their case with sweet reason, as there are still dark fears to allay.

1 B. Harrison, Separate Spheres: The Opposition to Women’s Suffrage in Britain (1978; 2013); J. Sutherland, Mrs Humphry Ward: Eminent Victorian, Pre-Eminent Edwardian (Oxford, 1990).

2 J. Eales, ‘Female Literacy and the Social Identity of the Clergy Family in the Seventeenth Century’, Archaeologia Cantiana, 133 (2013), pp. 67-81.

3 J.S. Mill, The Subjection of Women (1869; in Everyman edn, 1929), pp. 298-9.

4 By 1801, all women in Britain’s upper and middle classes were literate, and literacy was also spreading amongst lower-class women, especially in the growing towns.

5 Anon., Woman not Inferior to Man, by Sophia, a Person of Quality (1739), pp. 36, 38, 48.

6 Ibid., p. 51.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 65 please click here