MONTHLY BLOG 83, SEX AND THE ACADEMICS

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2017)

Appreciating sex means appreciating the spark of life. Educating numbers of bright, interesting, lively young adults is a sexy occupation. The challenge for academics therefore is to keep the appreciation suitably abstract, so that it doesn’t overwhelm normal University business – and absolutely without permitting it to escalate into sexual harassment of students who are the relatively powerless ones in the educational/power relationship.

It’s long been known that putting admiring young people with admirable academics, as many are, can generate erotic undertones. Having a crush on one’s best teacher is a common youthful experience; and at least a few academics have had secret yearnings to receive a wide-eyed look of rapt attention from some comely youngster.1 There is a spectrum of behaviour at University classes and social events, from banter, stimulating repartee and mild flirtation (ok as long as not misunderstood), all the way across to heavy power-plays and cases of outright harassment (indefensible).

|

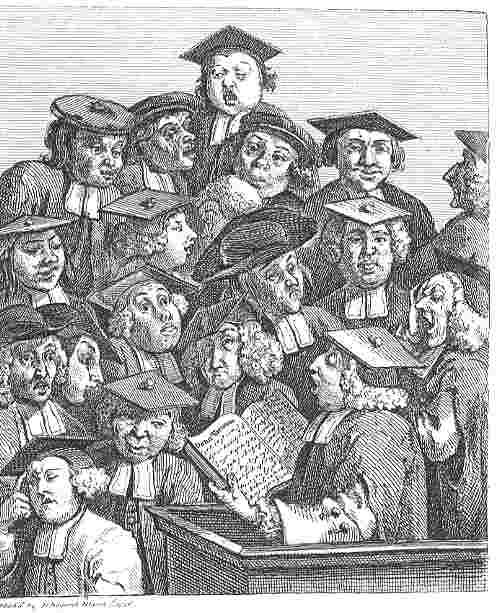

Fig.1 Hogarth’s Scholars at a Lecture (1736) satirises both don and students, demonstrating that bad teaching can have a positively anti-aphrodisiac effect. |

If academics don’t have the glamour, wealth and power of successful film producers, an eminent ‘don’ can still have a potent intellectual authority. I have known cases of charismatic senior authority figures imposing themselves sexually upon the gullible young, although I believe (perhaps mistakenly – am I being too optimistic here?) that such scenarios are less common today. That change has taken place partly because University expansion and grade escalation has created so many professors that they no longer have the same rarity value that once they did. It’s also worth noting that single academics don’t hold supreme power over individual student’s careers. Examination grades, prizes, appointments, and so forth are all dealt with by boards or panels, and vetted by committees.

Moreover, there’s been a social change in the composition of the professoriat itself. It’s no longer exclusively a domain of older heterosexual men (or gay men pretending publicly to be heterosexual, before the law was liberalised). No doubt, the new breed of academics have their own faults. But the transformation of the profession during the past forty years has diluted the old sense of hierarchy and changed the everyday atmosphere.

For example, when I began teaching in the early 1970s, it was not uncommon to hear some older male profs (not the junior lecturers) commenting regularly on the physical attributes of the female students, even in business meetings. It was faintly embarrassing, rather than predatory. Perhaps it was an old-fashioned style of senior male bonding. But it was completely inappropriate. Eventually the advent of numerous female and gay academics stopped the practice.

Once in an examination meeting, when I was particularly annoyed by hearing lascivious comments about the ample breasts of a specific female student, I tried a bit of direct action by reversing the process. In a meaningful tone, I offered a frank appreciation of the physique of a handsome young male student, with reference specifically to his taut buttocks. (This comment was made in the era of tight trousers, not as a result of any personal exploration). My words produced a deep, appalled silence. It suggested that the senior male profs had not really thought about what they were saying. They were horrified at hearing such words from a ‘lady’ – words which struck them not as ‘harmless’ good fun (as they viewed their own comments) but as unpleasantly crude.

Needless to say, I don’t claim that my intervention on its own changed the course of history. Nonetheless, today academic meetings are much more businesslike, even more perfunctory. Less time is spent discussing individual students, who are anyway much more numerous – with the result that the passing commentary on students’ physiques seems also to have stopped. (That’s a social gain on the gender frontier; but there have been losses as well, as today’s bureaucratised meetings are – probably unavoidably – rather tedious).

One important reason for the changed atmosphere is that more specific thought has been given these days to the ethical questions raised by physical encounters between staff and students. It’s true that some relationships turn out to be sincere and meaningful. It’s not hard to find cases of colleagues who have embarked upon long, happy marriages with former students. (I know a few). And there is one high-profile example on the international scene today: Brigitte Trogneux, the wife of France’s President Emmanuel Macron, first met her husband, 25 years her junior, when she was a drama teacher and he was her 15-year old student. They later married, despite initial opposition from his parents, and seem happy together.

But ethical issues have to take account of all possible scenarios; and can’t be sidelined by one or two happy outcomes. There’s an obvious risk academic/student sexual relationships (or solicitation for sexual relationships) can lead to harassment, abuse, exploitation and/or favouritism. Such outcomes are usually experienced very negatively by students, and can be positively traumatic. There’s also the possibility of anger and annoyance on the part of other students, who resent the existence of a ‘teacher’s pet’. In particular, if the senior lover is also marking examination papers written by the junior lover, there’s a risk that the impartial integrity of the academic process may be jeopardised and that student confidence in the system be undermined. (Secret lovers generally believe that their trysts remain unknown to those around them; but are often wrong in that belief).

As far as I know, many Universities don’t have official policies on these matters, though I have long thought they should. Now that current events, especially the shaming of Harvey Weinstein, have reopened the public debates, it’s time to institute proper professional protocols. The broad principles should include an absolute ban of all forms of sexual abuse, harassment or pressurising behaviour; plus, equally importantly, fair and robust procedures for dealing with accusations about such abusive behaviour, bearing in mind the possibility of false claims.

There should also be a very strong presumption that academic staff should avoid having consensual affairs with students (both undergraduate and postgraduate) while the students are registered within the same academic institution and particularly within the specific Department, Faculty or teaching unit, where the academic teaches.

Given human frailty, it must be expected that the ban on consensual affairs will sometimes be breached. It’s not feasible to expect all such encounters to be reported within each Department or Faculty (too hard to enforce). But it should become an absolute policy that academics should excuse themselves from examining students with whom they are having affairs. Or undertaking any roles where a secret partisan preference could cause injustice (such as making nominations for prizes). No doubt, Departments/Faculties will have to devise discreet mechanisms to operate such a policy; but so be it.

Since all institutions make great efforts to ensure that their examination processes are fairly and impartially operated, it’s wrong to risk secret sex warping the system. Ok, we are all flawed humans. But over the millennia humanity has learned – and is still learning – how to cope with our flaws. In these post-Weinstein days, all Universities now need a set of clear professional protocols with reference to sex and the academics.

|

Fig.2 Advertising still for Educating Rita (play 1980; film 1983), which explores how a male don and his female student learn, non-amorously, from one another. |

1 Campus novels almost invariably include illicit affairs: two witty exemplars include Alison Lurie’s The War between the Tates (1974) and Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man (1975). Two plays which also explore educational/personal tensions between a male academic and female student are Willy Russell’s wry but gentle Educating Rita (1990) and David Mamet’s darker Oleanna (1992).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 83 please click here

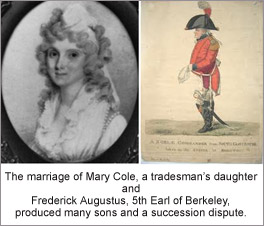

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator.

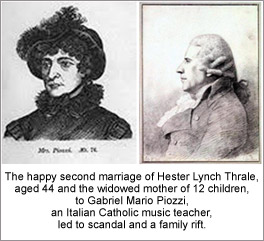

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator. So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury.

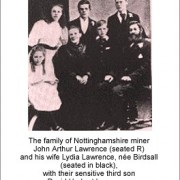

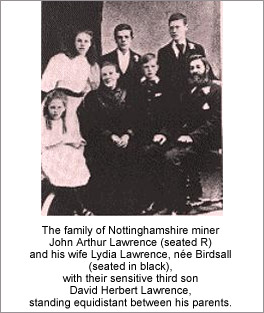

So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury. In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4

In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4