MONTHLY BLOG 78, WHO CARES? GETTING PEOPLE TO VOTE

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2017)

Elections again! And public moodiness at being asked to decide on weighty matters once more. The last thing that Britain’s campaigners for a democratic franchise ever imagined was that electors, once enfranchised, would not use their votes. Was it for nothing that the democratic campaigners known as the Chartists in the 1840s were thrown into gaol? or that imprisoned suffragettes in the 1900s were force fed? But it’s turned out that achieving a flourishing democracy, defined as the full participation of all citizens in the political process, requires more than simply legislating to extend the franchise.

People have to want to use their vote. One immediate possibility is to adopt the Australian system, where since 1924 it been compulsory for all citizens to register for elections and to cast a vote.1 Spoiling the ballot paper, to cast a non-vote, is allowed. It amounts to ‘abstaining in person’, to borrow a resonant phrase from Frank McGuire (an independent Irish Republican MP), when he travelled to the House of Commons from Belfast on 28 March 1979 but declined to vote to save the Callaghan government. It then fell by a margin of one vote, ushering in eleven years of Margaret Thatcher.

I personally hanker after the benefits of compulsory voting, provided that the system always gives scope for returning a blank paper. On the other hand, there are arguments against as well as for this process. Voters don’t always like it – their democratic choice? Hence some countries have switched from compulsory to optional systems. Take, for example, the Netherlands: in 1917, it introduced compulsory voting, along with the advent of a universal adult franchise; but in 1967 it abolished this requirement.

Another complication comes when voters resist compulsion, even while it remains their legal duty. That’s reported as happening in Brazil, which is the world’s largest country to have compulsory voting. Nonetheless, at the presidential election in 2014, over 30 million electors (about 21 percent of all those registered) did not vote. It’s still a good turnout but the sheer number of people flouting the law is very high. In effect, their aggregate non-participation means that compulsory voting has been de facto sidelined.

Anyway, in Britain this option is not on the political agenda. So what else might be done to encourage voting? One answer is instrumentalist. Tell young people in particular that their interests are being overlooked because their percentage participation has fallen steeply from the levels once taken as the norm in the postwar years. In 1992, 66% of young adults aged 18-24 and on the electoral register voted, compared with 38% in 2005 and 44% in 2015.2 And the decline is even larger, if the number of young people who are not on the electoral register is taken into account. No wonder politicians have turned their attention to the older generations and there is talk of ‘intergenerational warfare’.

It’s true that there are no reserved ‘student seats’, so young people’s votes are widely scattered across many constituencies. Hence many say (rather than ask): why bother? Nevertheless, politicians will get their statisticians to pore over survey data to see which demographic groups bothered to vote. So the answer is: you have to bother, to get noticed politically.

Yet it’s clearly not good enough to view the questions in purely instrumentalist terms. Voting means contributing to the full democratic community, not just calculating ‘what’s in it for me?’ So it’s sad and even sinister for the good health of a democracy to have lots of young people who are either apathetic or alienated. Spoiling one’s ballot paper is one thing. Not bothering to turn out to vote is bad news for society as a whole and also for the absentee young voters themselves. They are depriving themselves of constitutional involvement (no matter how dry and dusty) in the world in which they live: as it were, consigning themselves to victimhood.

So what can be done to encourage voting among the won’t-vote brigades of all ages? Some of the answers point to the politicians. Their campaigning styles, for example. Electors are alienated if those seeking their votes appear too robotic, lacking spontaneity and authenticity. Even more depends on politicians’ achievements in office. If they offer high and perform low, then cynicism becomes rife. (A degree of scepticism is good – but not corrosive cynicism).

There’s an additional major problem from the mainstream press, which loves melodrama. It slams politicians as robotic if they conform boringly to the party line but equally attacks them as confused or ignorant or dastardly if they stray the tiniest bit off-message. Let alone the problems generated and multiplied endlessly by the social media, which encourage an unsavoury mix of either undue adulation or venomous personal hostility.3

Another big looming question focuses upon how much governments themselves can buck the big impersonal trends of global history. So many things – like international finance markets, international businesses, international social media, international terrorism, international crime, world-wide climate change, environmental pollution, and so forth – seem to operate beyond the current scope of democratic control and regulation, which is depressing, to say the least.4 If politicians in a national forum seem powerless, then no wonder that individual voters at grass roots level feel even less in control of their own or the nation’s destiny. But, in response to such challenges, the answers have to be more, not less, democratic engagement.

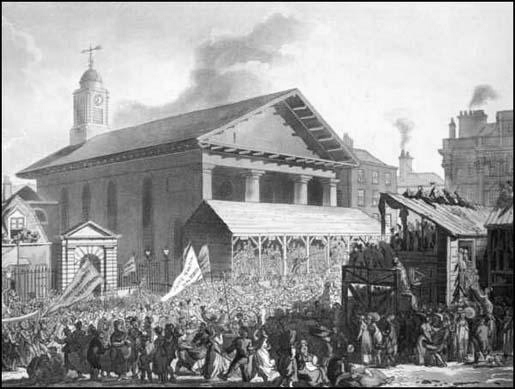

It’s not just the politicians who are responsible. So what about the voting process itself? Can the system be made more user-friendly? In the eighteenth century (in the minority of large constituencies with a wide franchise), voters cast their votes publicly.5 An election was a community occasion, with elements of the carnivalesque. Crowds turned out to hear the candidates speak from the open hustings and to cheer or boo the electors as they voted. Flags were flown and party favours sported. The fact that voters literally stood up to be counted, before all their friends and neighbours, made open voting the purest form of voting, in the opinion of the liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill. It would force citizens to think of the public good, and not just their personal self-interest: ‘The best side of their character is that which people are anxious to show’.6

| Fig.2 Rowlandson’s 1808 view of a Westminster parliamentary election, where candidates address the crowds from the specially constructed wooden hustings, erected in front of St Paul’s Covent Garden. |

But, ever since the introduction of the secret ballot (1872 in Britain), the process of voting lost its element of community participation. And that’s become even more noticeable since the advent of postal voting on demand (2001 in Britain). The process has become not just secret but utterly individualised and secretive. No doubt that’s one of the reasons that the traditional party posters have virtually disappeared from people’s windows.

There were and are excellent reasons to protect electors from undue pressure. But it’s not good to lose the excitement and community involvement involved in an election, which is a collective event with a collective impact.

Perhaps there might be parties or at least a cup of tea on offer for those who vote in person in polling stations? And/or an on-line App for millions of people to record: ‘I’ve voted! Have you?’ And what about practice elections in schools? And constituency or regional Youth Parliaments? And networks of local societies – and/or student societies – linked for campaigning purposes? Let alone shop-floor democracy at work? And ways for isolated workers in large-scale enterprises to link up into organised networks? Plus, of course, an effective electoral registration system, which encourages rather than discourages people to get into the system.

Political life should never be a simple top-down process. Instead, democracy is an entire lifestyle and lifetime commitment to participation. Voters are invited to insert their own meanings into the processes. All the same, it’s no surprise that the Chartist demand for annual parliamentary elections is the only item of their visionary six-point programme that has not yet been adopted.7 Moreover, voters’ election-fatigue suggests that it is unlikely to gain mass support any time soon. Instead, it’s more important to revise and update the electoral processes to recover full community involvement in a true community event.

1 The information in this and the following two paragraphs comes from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compulsory_voting

2 E. Phelps, ‘Young Adults and Electoral Turnout in Britain: Towards a Generational Model of Political Participation’ (University of Sussex European Institute [SEI], Working Paper 92, 2006); ‘Why Aren’t Young People Voting?’ University of Warwick Background Paper’ (c.2006); and http://www.if.org.uk/archives/6576/how-high-was-youth-turnout-at-the-2015-general-election

3 Among a growing literature, see e.g. A. Bruns and others (eds), The Routledge Companion to Social Media and Politics (2015); T. Highfield, Social Media and Everyday Politics (Cambridge, 2016); S. Shaked (ed.), The Impact of Social Media on Collective Action (Oxford, 2017).

4 For a meditation on that theme, see J. Lanchester, ‘Between Vauxhall and Victoria’, in London Review of Books, 39/11 (1 June 2017), pp. 3.6.

5 See variously P.J. Corfield, ‘What’s Wrong with the Old Practice of Open Voting, Standing Up to be Counted?’ Monthly BLOG/53 (May 2015), in https://www.penelopejcorfield.com/monthly-blogs/; and website ‘London Electoral History, 1700-1850’, www.londonelectoralhistory.com.

6 J.S. Mill, Considerations upon Representative Government (1861), ed. C.V. Shields (New York, 1958), pp. 154-64, esp. p. 164.

7 The Chartists’ six demands were: (1) universal adult male franchise (achieved in 1918; and matched by the adult female franchise in 1928); (2) voting by secret ballot (achieved in 1872); (3) equal representation via roughly equal sized-constituencies (implemented by an independent electoral commission from 1885 onwards); (4) no property qualification for candidates to stand as MP (achieved 1858); (5) payment for MPs (achieved 1911); and (6) annual parliamentary elections (not achieved). See M. Chase, Chartism: A New History (Manchester, 2007); D. Thompson, The Dignity of Chartism: Essays by Dorothy Thompson, ed. S. Roberts (2015).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 78 please click here