MONTHLY BLOG 45, DOFFING ONE’S HAT

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2014)

TV’s Pride and Prejudice (1995) provided many memorable images, not least Colin Firth as Mr Darcy diving into a pool to emerge reborn as a feeling, empathetic human being. This transformation gains extra impact when contrasted with the intense formality of his general deportment. When, after some months of absence, Darcy and Bingley re-enter the Bennet family home at Longbourn, they bow deeply in unison, whilst Mrs Bennet and all her daughters rise as one and bend their heads in synchronised response. Audiences may well sigh, admiringly or critically according to taste. What a contrast with our own casual manners. It satisfies a sense that the past must have been different – like a ‘foreign country’, in a much-cited phrase from L.P. Hartley.1

But did people in Georgian polite society actually greet each other like that on a day-to-day basis? There is good evidence for the required formality (and dullness) of Hanoverian court life on ceremonial occasions. A fashionable ball or high society dinner might also require exceptional courtesies. But ordinary life, even among the elite of Britain’s landed aristocrats and commercial plutocrats, was not lived strictly according to the etiquette books.

Instead, the eighteenth century saw an attenuation of the lavish old-style formalities, which were known as ‘hat honour’. In theory, men when meeting their social superiors made a deep bow, removing their headgear, with a visible flourish. Gentlemen greeting a ‘lady’ would also remove their hats with a courteous nod. For women, the comparable requirement was the low curtsey from the ‘inferior’ to the ‘superior’. Those who held their heads highest (and hatted in the case of men) the more socially elevated, since lowering the head always signalled deference. This understanding underpins the custom of addressing monarchs as ‘Your Highness’.

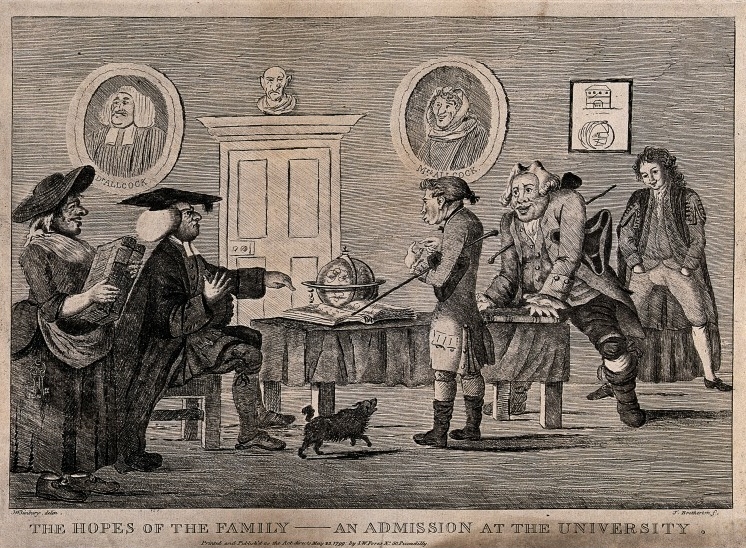

Illustration 1 ‘The Hopes of the Family’ (1799) shows a young man being interviewed for University admission. A don presides, wearing his mortar board, whilst the nervous applicant and his eager father, an old-fashioned country gentleman, have both doffed their hats, which they carry under their arms. An undergraduate in his gown looks on nonchalantly, his hands in pockets. Yet he too remains bare-headed in the presence of a senior member of his College. Only the applicant’s mother, who is subject to the different rules of etiquette for women, covers her head with a rustic bonnet.

|

Illus 1: A gentle satire by Henry William Bunbury, entitled The Hopes of the Family (1799) – © The Welcome Library. |

In accordance with this etiquette, King Charles I on trial before Parliament in 1648 wore a high black hat throughout the proceedings. It was a signal that, as the head of state, he would not uncover for any lower authority. The answer of his republican opponents was radical. Charles I was found guilty of warfare against his own people, as a ‘tyrant, traitor and murderer’. He was decapitated, beheading the old power structure very literally and publicly.

After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, there was some return to the old formalities. (Or at least hopes of the same). For example, in October 1661 the naval official and MP Samuel Pepys recorded his displeasure at what he considered to be the undue pride of his manservant, who kept his hat on in the house.2 Pepys expected deference from his ‘inferiors’, whilst being ready to accord it to his own ‘superiors’. But it was not always easy to judge. In July 1663, Pepys worried that he may have offended the Duke of York, by not uncovering when the two men were walking in sight of each other in St James’s Park.3 It was a tricky decision. Failure, to doff one’s hat, when close at hand, would be rude, yet uncovering from too far away would seem merely servile.

Over the very long term, however, all these formalities began to attenuate. With the advent of brick buildings and roaring coal-fires, the habitual wearing of hats indoors generally disappeared – mob-caps and night-caps excepted. And in public, the old gestures continued but in an attenuated form. With commercial growth came the advent of many people of middling status. It was hard for them to calculate the precise gradations of status between one individual and another. The old-style mannerisms were also too slow for a fast-moving and urbanising world.

As a result, between men the deep bow began to change into a nod of the head. The elaborate flourish of the hat gradually turned into a quick lifting or pulling. And the respectful long tug of the forelock, on the part of those too poor to have any headgear, turned into a briefer touch to the head.4

A notable example of the abbreviation of hat honour was the codification of the military salute. It was impractical for rank-and-file soldiers to remove their headgear whenever encountering their officers. On the other hand, military discipline required the respecting of ranks. The answer was a symbolic gesture. ‘Inferiors’ greeted their ‘superiors’ by touching the hand to the head. Different regiments evolved their own traditions. Only in 1917 (well into World War I) did the British army decide that all salutes should be given right-handedly.

Meanwhile, the female greeting in the form of a low curtsey, holding out the dress, also evolved into a briefer bob or half-curtsey. It was expected from all lower-status women when meeting ‘superiors’. But hat honour was confined to men. On public occasions, women retained their hats, bonnets and feathers. Even in church, they did not copy men in baring their heads but respected St Paul’s Biblical dictum that it was not ‘comely’ for women to pray to God uncovered.5

These etiquette rules delight TV- and film-makers. In reality, however, the conventions were always in evolution. Rules were broken and/or fudged, as well as followed. Moreover, by the later eighteenth-century in Britain a new form of interpersonal greeting had arrived. It was the egalitarian hand-shake. Jane Austen’s characters not only bowed and curtsied to each other. They also, in certain circumstances, shook hands. In one Austen novel, a fearlessly ‘modern’ young woman extends her hand to shake that of a young man at a public assembly. Anyone know the reference? Answer follows in next month’s BLOG on Handshaking.

1 L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between (1943, p. 1: ‘the past is a foreign country – they do things differently there’.

2 R. Latham and W. Matthews (eds), The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Vol. II: 1661 (1970), p 199.

3 Ibid., Vol. IV: 1663 (1971), p. 252.

4 P.J. Corfield, ‘Dress for Deference & Dissent: Hats and the Decline of Hat Honour’, Costume: Journal of the Costume Society, 23 (1989), pp. 64-79; also transl. in K.Gerteis (ed.), Zum Wandel von Zeremoniell und Gesellschaftsritualen: Aufklärung, 6 (1991), pp. 5-18. Also posted on PJC personal website as Pdf/8.

5 Holy Bible, 1 Corinthians, 11:13.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 45 please click here