If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2019)

|

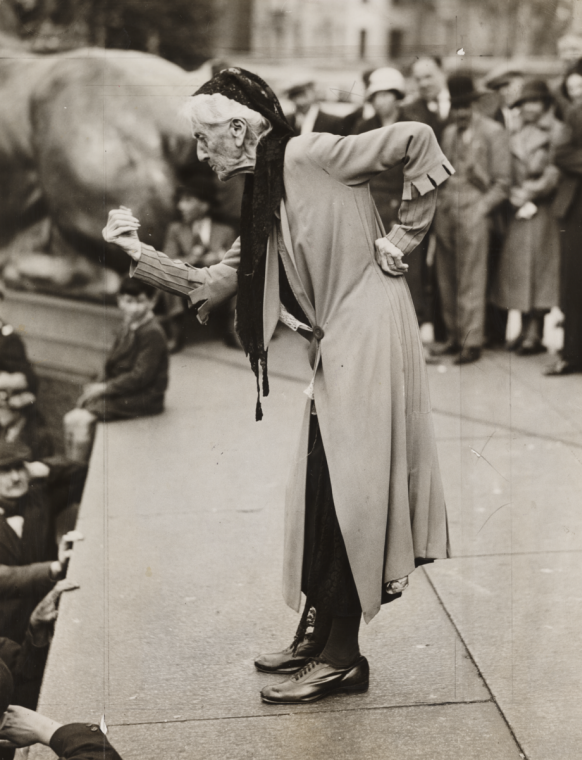

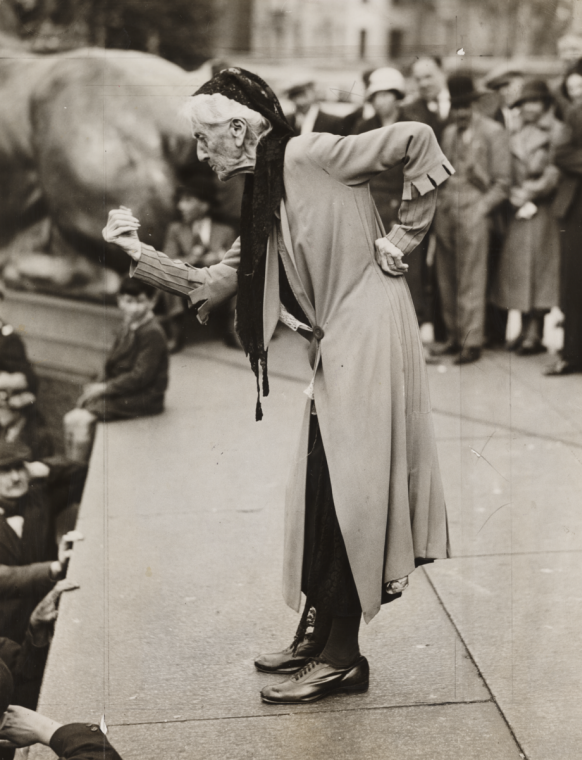

Fig.1 Charlotte Despard speaking at an anti-fascist rally, Trafalgar Square, 12 June 1933:

photograph by James Jarché, Daily Herald Archive.

|

Charlotte Despard (1844-1939) was a remarkable – even amazing – woman. Don’t just take my word for it. Listen to Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948). Visiting London in 1909, he met all the leading suffragettes. The one who impressed him most was Charlotte Despard. She is ‘a wonderful person’, he recorded. ‘I had long talks with her and admire her greatly’.1 They both affirmed their faith in the non-violent strategy of political protest by civil disobedience. Despard called it ‘spiritual resistance’.

What’s more, non-violent protest has become one of the twentieth-century’s greatest contributions to potent mass campaigning – without resorting to counter-productive violence. Associated with this strategy, the names of Henry Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, all controversial in their day, have become canonised.2 Yet Charlotte Despard, who was also controversial in her day, has been substantially dropped from the historical record.

Not entirely so. On 14 December 2018 Battersea Labour unveiled a blue plaque in her honour, exactly one hundred years after the date when she stood as the Labour Party candidate in North Battersea in the 1918 general election. She was one of the feminist pioneers, when no more than sixteen women stood. But Despard lost heavily to the Liberal candidate, even though industrial North Battersea was then emerging as a Labour stronghold.3

And one major reason for her loss helps to explain her disappearance from mainstream historical memory. Despard was a pacifist, who opposed the First World War and campaigned against conscription. Many patriotic voters in Battersea disagreed with this stance. In the immediate aftermath of war, emotions of relief and pride triumphed. Some months later, Labour swept the board in the 1919 Battersea municipal elections; but without Charlotte Despard on the slate.

Leading pacifists are not necessarily all neglected by history.4 But the really key point was that Charlotte Despard campaigned for many varied causes during her long life and, at every stage, weakened her links with previous supporters. Her radical trajectory made complete sense to her. She sought to befriend lame dogs and to champion outsiders. Yet as an independent spirit – and seemingly a psychological loner – she walked her own pathway.

Despard was by birth an upper crust lady of impeccable Anglo-Irish ancestry, with high-ranking military connections. For 40 years, she lived quietly, achieving a happy marriage and a career as a minor novelist. Yet, after being widowed at the age of 40, she had an extraordinary mid- and late-life flowering. She moved to Battersea’s Nine Elms, living among the poorest of the poor. And she then became a life-long radical campaigner. By the end of her career, she was penniless, having given all her funds to her chosen causes.

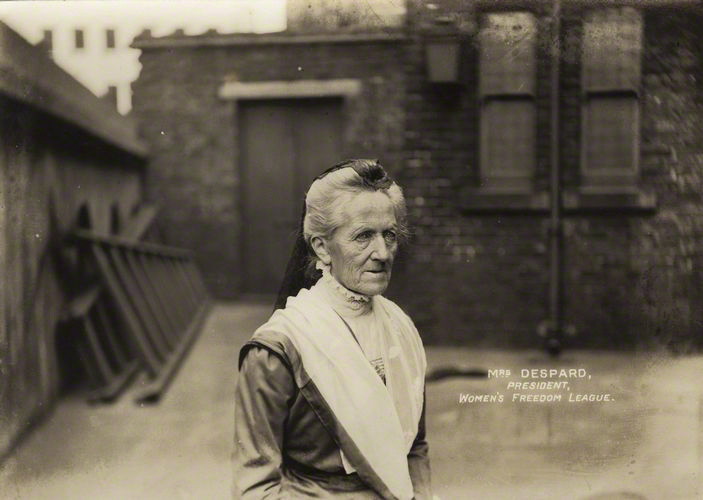

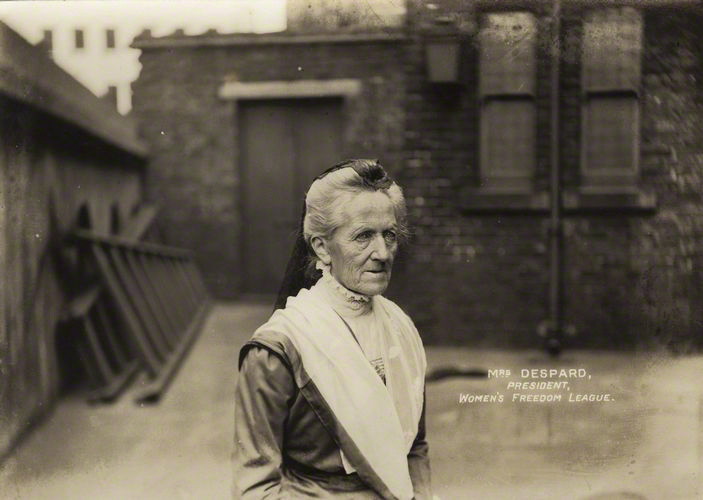

A convinced suffragette, Despard joined the Women’s Social and Political Union and was twice imprisoned for her public protests. In 1907, however, she was one of the leading figures to challenge the authoritarian leadership style of Christabel Pankhurst. Despard resigned and founded the rival Women’s Freedom League. This smaller group opposed the use of violence. Instead, its members took symbolic action, like unfurling banners in parliament. They also advocated passive resistance, like non-payment of taxation and non-cooperation with the census. (I recently discovered, thanks to the research of a family member, that my great-grandmother was a would-be WFL supporter. So the 1911 census enumerator duly noted that Mrs Matilda Corfield, living in Sheffield, had given information only ‘under Protest (she wants the vote)’.5 This particular example of resistance was very muffled and inconsequential. Nevertheless, it indicated how unknown women across the country tried to respond to WFL advice. It was one way of slowly changing the climate of public opinion.)

However, the energetic Charlotte Despard did not confine her efforts solely to the cause of the female suffrage. Her life in Battersea radicalised her politically and she became a socialist. She was not good at detailed committee work. Her forte was activism. Indefatigably, she organised a local welfare system. She funded health centres for mothers and babies, exchange points for cots and equipment, youth clubs, and halls for local meetings. And the front room of her small premises in Nine Elms was made available to the public as a free reading room, stocked with books and newspapers. It was a one-woman exercise in practical philanthropy. What’s more, her 1918 election manifesto called for a minimum wage – something not achieved until 1998.

Among the Battersea workers, the tall, wiry, and invariably dignified Charlotte Despard cut an impressive figure. A lifelong vegetarian, she was always active and energetic. And she believed in the symbolic importance of dress. Thus she habitually wore sandals (or boots in winter) under long, flowing robes, a lace shawl, and a mantilla-like head-dress. The result was a timeless style, unconcerned with passing fashions. She looked like a secular sister of mercy.

| Fig.2 Charlotte Despard in the poor tenements of Battersea’s Nine Elms, where she lived from 1890 to the early 1920s, instituting and funding local welfare services. Her visitors commented adversely on the notorious ‘Battersea smell’ of combined industrial effluent and smoke from innumerable coalfires; but Despard reportedly took no notice. |

For a number of years, Despard worked closely with the newly founded Battersea Labour Party (1908- ), strengthening its global connections. She attended various international congresses; and she backed the Indian communist Shapurji Saklatvala as the Labour-endorsed candidate in Battersea North at the general election in 1922. (He won, receiving over 11,000 votes). Yet, as already noted, the Battersea electorate in 1918 had rebuffed her own campaign.

Then at a relatively loose end, Despard moved to Dublin in the early 1920s. She had already rejected her Irish Ascendancy background by converting to Catholicism. There she actively embraced the cause of Irish nationalism and republicanism. She became a close supporter of Maud Gonne, the charismatic exponent of Irish cultural and political independence. By the later 1920s, however, Despard was unhappy with the conservatism of Irish politics. In 1927 she was classed as a dangerous subversive by the Free State, for opposing the Anglo-Irish Treaty settlement. She eventually moved to Belfast and changed tack politically to endorse Soviet communism. She toured Russia and became secretary of the British Friends of the Soviet Union (FSU), which was affiliated to the International Organisation of the same name.

During this variegated trajectory, Despard in turn shocked middle-class suffragettes who disliked her socialism. She then offended Battersea workers who rejected her pacifism. She next infuriated English Protestants who hated her Irish nationalism. And she finally outraged Irish Catholics (and many Protestants as well) who opposed her support for Russian communism. In 1933, indeed, her Dublin house was torched and looted by an angry crowd of Irish anti-communists.6

In fact, Despard always had her personal supporters, as well as plentiful opponents. But she did not have one consistent following. She wrote no autobiography; no memorable tract of political theory. And she had no close family supporters to tend her memory. She remained on good terms with her younger brother throughout her life. But he was Sir John French, a leading military commander in the British Army and from 1918 onwards Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. The siblings disagreed politically on everything – although both shared the capacity to communicate on easy terms with people from many different backgrounds. To the Despards, ‘Aunt Lottie’ was thus an eccentric oddity. To other respectable family friends, she was ‘a witch’, and a dangerous one at that.7

These factors combined together to isolate Despard and to push her, after her death, into historical limbo. There are very few public monuments or memorials to her indomitable career. In north London, a pleasant pub on the Archway Road is named after her, on land which was owned by her husband Colonel Despard. On Battersea’s Doddington Estate, there is an avenue named after her, commemorating her welfare work in the area. And now there is the blue plaque outside the headquarters of Battersea Labour at 177 Lavender Hill, SW11. These memorials are fine but hardly enough.

|

Fig.3 Blue plaque to Charlotte Despard, outside 177 Lavender Hill, London SW11 5TE: installed 14 December 2018, on the precise centenary of her standing for parliament in 1918, as one of only 16 women pioneers to do so.

|

Why should she be remembered? The answer is not that everyone would have agreed (then or later) with all of Charlotte Despard’s political calls. As this account has shown, she was always controversial and, on Russia, self-deceived into thinking it much more of a workers’ paradise than it was (as were many though not all left-leaning intellectuals in the West). Nonetheless, she is a remarkable figure in the history of public feminism. She not only had views but she campaigned for them, using her combination of practical on-the-ground organisation, her call for symbolic non-violent protest and ‘spiritual resistance’, and her public oratory. And she did so for nigh on 50 years into her very advanced years.

Indomitability, peaceful but forceful, was her signature style. She quoted Shelley on the need for Love, Hope, and Endurance. When she was in her mid-sixties, she addressed a mass rally in Trafalgar Square (of course, then without a microphone). Her speeches were reportedly allusive and wide-ranging, seeking to convey inspiration and urgency. One onlooker remembered that her ‘thin, fragile body seemed to vibrate with a prophecy’.8

Appropriately for a radical campaigner, Charlotte Despard’s last major public appearance was on 12 June 1933, when she spoke passionately at a mass anti-fascist rally in Trafalgar Square. At that time, she was aged 89. It was still unusual then for women to speak out boldly in public. They often faced jeers and taunts for doing so. But the photographs of her public appearances show her as unflinching, even when she was the only woman amidst crowds of men. Above all, for the feminist feat of speaking at the mass anti-fascist rally at the age of 89, there is a good case for placing a statue on Trafalgar Square’s vacant fourth plinth, showing Despard in full oratorical flow. After all, she really was there. And, if not on that particular spot, then somewhere relevant in Battersea. Charlotte Despard, born 175 years ago and campaigning up until the start of the Second World War, was a remarkable phenomenon. Her civic and feminist commitment deserves public commemoration – and in a symbolic style worthy of the woman.

Figs 4 + 5: Photos showing Despard, speaking in Trafalgar Square, without a microphone:

(L) dated 1910 when she was 66, and (R) dated 1933 when she was aged 89.

Her stance and demeanour are identically rapt, justifying one listener’s appreciative remark:

‘Mrs Despard – she always gets a crowd’. |

1 Quoted in M. Mulvihill, Charlotte Despard: A Biography (1989), p. 86. See also A. Linklater, An Unhusbanded Life: Charlotte Despard, Suffragette, Socialist and Sinn Feiner (1980); and, for Battersea context, P.J. Corfield in Battersea Matters (Autumn 2016), p. 11; and PJC with Mike Marchant, DVD: Red Battersea: One Hundred Years of Labour, 1908-2008 (2008).

2 A. Roberts and T. Garton Ash (eds), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-Violent Action from Gandhi to the Present (Oxford, 2009); R.L. Holmes and B.L. Gan (eds), Nonviolence in Theory and Practice (Long Grove, Illinois, 2012).

3 1918 general election result for North Battersea: Richard Morris, Liberal (11,231 = 66.6% of all voting); Charlotte Despard, Labour (5,634 = 33.4%). Turnout = 43.7%.

4 P. Brock and N. Young, Pacifism in the Twentieth Century (New York, 1999).

5 With thanks to research undertaken by Annette Aseriau.

6 Mulvihill, Charlotte Despard, p. 180.

7 Ibid., pp. 46-7, 78-9.

8 Account by Christopher St John, in Mulvihill, Charlotte Despard, p. 77.

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 97 please click here