MONTHLY BLOG 38, WHY IS THE LANGUAGE OF ‘RACE’ HOLDING ON SO LONG WHEN IT’S BASED ON A PSEUDO-SCIENCE?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2014)

Of course, most people who continue to use the language of ‘race’ believe that it has a genuine meaning – and a meaning, moreover, that resonates for them. It’s not just an abstract thing but a personal way of viewing the world. I’ve talked to lots of people about giving up ‘race’ and many respond with puzzlement. The terminology seems to reflect nothing more than the way things are.

But actually, it doesn’t. It’s based upon a pseudo-science that was once genuinely believed but has long since been shown as erroneous by geneticists. So why is this language still used by people who would not dream of insisting that the earth is flat, or the moon made of blue cheese.

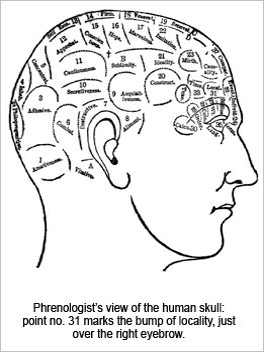

Part of the reason is no doubt the power of tradition and continuity – a force of history that is often under-appreciated.1 It’s still possible to hear references to people having the ‘bump of locality’, meaning that they have a strong topographical/spatial awareness and can find their way around easily. The phrase sounds somehow plausible. Yet it’s derived from the now-abandoned study of phrenology. This approach, first advanced in 1796 by the German physician F.J. Gall, sought to analyse people’s characteristics via the contours of the cranium.2 It fitted with the ‘lookism’ of our species. We habitually scrutinise one another to detect moods, intentions, characters. So it may have seemed reasonable to measure skulls for the study of character.

Yet, despite confident Victorian publications explaining The Science of Phrenology3 and advice manuals on How to Read Heads,4 these theories turned out to be no more than a pseudo-science. The critics were right after all. Robust tracts like Anti-Phrenology: Or a Chapter on Humbug won the day. Nevertheless, some key phrenological phrases linger on.5 My own partner in life has an exceptionally strong sense of topographical orientation. So sometimes I joke about his ‘bump of locality’, even though there’s no protrusion on his right forehead. It’s a just linguistic remnant of vanished views.

Yet, despite confident Victorian publications explaining The Science of Phrenology3 and advice manuals on How to Read Heads,4 these theories turned out to be no more than a pseudo-science. The critics were right after all. Robust tracts like Anti-Phrenology: Or a Chapter on Humbug won the day. Nevertheless, some key phrenological phrases linger on.5 My own partner in life has an exceptionally strong sense of topographical orientation. So sometimes I joke about his ‘bump of locality’, even though there’s no protrusion on his right forehead. It’s a just linguistic remnant of vanished views.

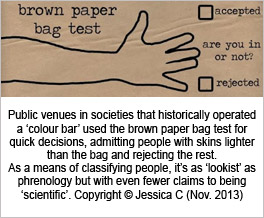

That pattern may apply similarly in the language of race, which is partly based upon a simple ‘lookism’. People who look like us are assumed to be part of ‘our tribe’. Those who do not seem to be ‘a race apart’ (except that they are not). The survival of the phrasing is thus partly a matter of inertia.

Another element may also spring, paradoxically, from opponents of ‘racial’ divisions. They are properly dedicated to ‘anti-racism’. Yet they don’t oppose the core language itself. That’s no doubt because they want to confront prejudices directly. They accept that humans are divided into separate races but insist that all races should be treated equally. It seems logical therefore that the opponent of a ‘racist’ should be an ‘anti-racist’. Statistics of separate racial groups are collected in order to ensure that there is no discrimination.

Yet one sign of the difficulty in all official surveys remains the utter lack of consistency as to how many ‘races’ there are. Early estimates by would-be experts on racial classification historically ranged from a simplistic two (‘black’ and ‘white’) to a complex 63.6 Census and other listings these days usually invent a hybrid range of categories. Some are based upon ideas of race or skin colour; others of nationality; or a combination And there are often lurking elements of ‘lookism’ within such categories (‘black British’), dividing people by skin colour, even within the separate ‘races’.7

So people like me who say simply that ‘race’ doesn’t exist (i.e. that we are all one human race) can seem evasive, or outright annoying. We are charged with missing the realities of discrimination and failing to provide answers.

Nevertheless, I think that trying to combat a serious error by perpetrating the same error (even if in reverse) is not the right way forward. The answer to pseudo-racism is not ‘anti-racism’ but ‘one-racism’. It’s ok to collect statistics about nationality or world-regional origins or any combination of such descriptors, but without the heading of ‘racial’ classification and the use of phrases that invoke or imply separate races.

What’s in a word? And the answer is always: plenty. ‘Race’ is a short, flexible and easy term to use. It also lends itself to quickly comprehensible compounds like ‘racist’ or ‘anti-racist’. Phrases derived from ethnicity (national identity) sound much more foreign in English. And an invented term like ‘anti-ethnicism’ seems abstruse and lacking instant punch.

What’s in a word? And the answer is always: plenty. ‘Race’ is a short, flexible and easy term to use. It also lends itself to quickly comprehensible compounds like ‘racist’ or ‘anti-racist’. Phrases derived from ethnicity (national identity) sound much more foreign in English. And an invented term like ‘anti-ethnicism’ seems abstruse and lacking instant punch.

All the same, it’s time to find or to create some up-to-date phrases to allow for the fact that racism is a pseudo-science that lost its scientific rationale a long time ago. ‘One-racism’? ‘Humanism’? It’s more powerful to oppose discrimination in the name of reality, instead of perpetrating the wrong belief that we are fundamentally divided. The spectrum of human skin colours under the sun is beautiful, nothing more.

1 On this, see esp. PJC website BLOG/1 ‘Why is the Formidable Power of Continuity so often Overlooked?’ (Nov. 2010).

2 See T.M. Parssinen, ‘Popular Science and Society: The Phrenology Movement in Early Victorian Britain’, Journal of Social History, 8 (1974), pp. 1-20.

3 J.C. Lyons, The Science of Phrenology (London, 1846).

4 J. Coates, How to Read Heads: Or Practical Lessons on the Application of Phrenology to the Reading of Character (London, 1891).

5 J. Byrne, Anti-Phrenology: Or a Chapter on Humbug (Washington, 1841).

6 P.J. Corfield, Time and the Shape of History (London, 2007), pp. 40-1.

7 The image comes from Jessica C’s thoughtful website, ‘Colorism: A Battle that Needs to End’ (12 Nov. 2013): www.allculturesque.com/colorism-a-battle-that-needs-to-end.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 38 please click here