MONTHLY BLOG 121, BEING ASSESSED AS A WHOLE PERSON – A CRITIQUE OF IDENTITY POLITICS

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2021)

[PJC Pdf/58]

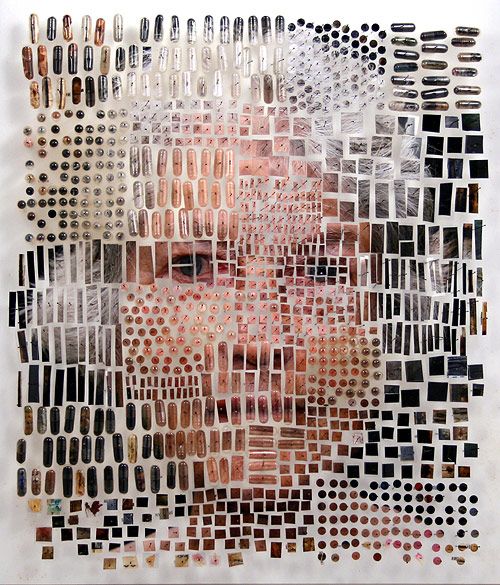

| One of series of Dissected Photographs by New York artist © Michael Mapes |

Friends: I want to be taken seriously as a whole person, assessed in the round. It’s positively good to feel part of a universalist personhood.1 Something that is experienced in common with all fellow humans. But how is that attitude to be encouraged, whilst simultaneously acknowledging the benefits that separatist identity politics can bring?

Social groups who have been marginalised – victims of an oppressive history – obviously gain a great deal by asserting their claims to general appreciation. Black Lives Matter. Of course they do: unequivocally and absolutely. It’s a proposition that draws strength from its utter truth.

One among the many challenges of identity politics, however, is the question of definition. Who decides who is or is not aligned with which particular identity? What happens when others persistently allocate you (for example, because of your looks) with a group with whom you personally feel little or no affinity? People of mixed ethnic heritage sometimes feel doubly excluded: their skins perhaps not dark enough for a ‘real’ Black identity, but not pale enough for a ‘real’ White one. Or perhaps children of mixed marriages may physically resemble one parent, whilst emotionally identifying with the other. What chance do such individuals have of asserting their inner sense of identity, when society instantly classifies them with the parent they physically resemble?

That point highlights another related problem of definition. An individual may have – indeed most do have – multiple identities. In my case, I could be described (variously) as a white, middle-class, heterosexual, childless woman, living in a stable partnership; as well as a Yorkshire-born Londoner, with English, British and/or European affiliations; as well as: an older person; as tolerably well-off; as a home-owner with a pension; as a coeliac (with a chronic gluten-allergy); as someone with short sight; as a professor; as an academic historian; as a bibliophile; as a left-winger; as an agnostic, reared in a cultural tradition of secularised Protestant Dissent; as a keen swimmer; as a music fan; as an amateur gardener; as a cat-lover; as someone with a sense of humour; … as an optimist … Any of those characteristics might be used to ascribe to me a cultural identity. Some of them I would warmly endorse. Others would leave me cold, as being true (childlessness) but not being at all central to my self-definition. And yet another of those terminologies would fill me with horror. I am (or so the calendar tells me) an old woman; but I emphatically don’t self-identify as such.

There are clearly differences between what one might term ‘objective’ personal identifiers and ‘subjective’ ones. There are also different experiences in a person’s lifetime when some affiliations might assume more importance than others. For example, a sense of patriotic resistance is likely to be strongly aroused if one’s own country suddenly comes under unprovoked attack from a hostile overseas tyranny. And a sense of internationalism is conversely likely to be strengthened if one’s own country is engaged in aggressive and bloody militarism against a harmless and defenceless overseas people, whose sole act of provocation lies in their happening to inhabit strategically important or resource-rich territory.

In other words, people have multiple identities. Some of these are more important at some points in a lifetime than are others. And, indeed, some identities might seem to clash with others. For example, it is sometimes assumed that all people with capital assets should always strive to gain the maximum from their investments and to pay as little tax as possible. (Tax advisers often assert that explicitly).

Yet it can equally be argued that property-owners with a civic conscience – and also acting out of enlightened self-interest – should want to pay more taxes in order to reduce inequalities, relieve poverty, reduce environmental degradation, and promote a more harmonious and just society. These are matters of judgment, clearly. Not simply a reflex response to owning property. (One complaint about so-called ‘identity politics’ is that the concept may encourage electors to vote purely for their own immediate personal benefit rather than for wider civic considerations.2 But, in practice, voters have a multitude of concerns in play at any given point).

Identities are actually so intricate and simultaneously so personal that any cultural politics based upon stereotypical assumptions is offensive to the individuals involved. It’s annoying to be told what one is likely to think ‘as a woman’. It’s infuriating to be told that one is intrinsically and automatically a racist oppressor because of one’s light skin colour. That assertion leaves no scope for moral growth and change. White people in many societies may, for example, be initially unaware of their ethnic privileges and may share inherited prejudices about their fellow humans. Yet such views can be overturned, sometimes dramatically, sometimes gradually. As the former slave-trader John Newton wrote movingly from personal experience, in Amazing Grace: ‘My eyes were blind, yet now I see…’3

Furthermore, before getting back to the universalist concept of personhood, let’s also acknowledge that identity politics are not just invoked these days for the purpose of warm, affirmative rectifications of historic injustice. Separating people by group classification may well provoke a serious backlash. Black Lives Matter is currently opposed by a number of far-right white supremacist groups. Interestingly (on the theme of complex identities), the all-male Proud Boys in the USA include members of mixed heritage, including the current leader who identifies as Afro-Cuban, while their collective ethos is one of aggressive pro-Western, anti-feminist and anti-socialist masculinity.4

Underlying these divisions, however, there remains the universalist concept of common personhood. There are communal human characteristics and communal interests. It is thus not always relevant to enquire about the detailed personal circumstances of each individual. Being a person is enough.

Such a view was expressed with clarion force in 1849 by the young author Charlotte Brontë. She first published as Currer Bell, deliberately choosing a name which concealed her gender identity. Writing to her male publisher, she urged him to forget the conventional courtesies between the sexes.5 Those niceties too often implied condescension from the ‘superior’ male to an ‘inferior’ female. She wanted to be judged on fair terms. So Brontë urged upon him that:

to you, I am neither Man nor Woman – I come before you as an Author only – it is the sole standard by which you have a right to judge me – the sole ground on which I accept your judgment.

It was a spirited invention from a budding novelist to an established figure in the world of publishing. Charlotte Brontë’s claim thus falls within the history of personhood, and within the history of meritocracy too. And these are themes of great relevance and topicality today. Interest in individual personhood (or self) is coming up on the ropes, alongside the huge publishing boom in studies of ‘identity’. Evidence can be found in debates within philosophy,6 ethics,7 animal rights,8 theology,9 politics,10 psychology,11 law,12 anthropology,13 social welfare,14 economics,15 electoral history,16 literary studies,17 even contemporary poetry18

Becoming vividly aware of past and present injustices – and the need for systematic redress – is certainly a necessary stage in today’s identity politics. It’s understandable that people who have been stigmatised for their gender; sexuality; religion; nationality; ethnic identity; class position; personal disability; or any other quality need to express solidarity with others in like circumstances – and to get respect and contrition from the wider society, It’s also true that sometimes a counter-vailing mantle of universalism can be used as a smoke screen to hide sectional interests. Yet it is to be hoped that, in the long run, a celebration of truly shared and egalitarian human personhood will prevail. In the meantime, dear friends, please judge this communication as coming not from someone representing any one of the separate descriptive categories listed in paragraph four (above); but from a whole person.

ENDNOTES:

1 A slightly shorter version of this text appears online in Academia Letters (Jan. 2021): ; and it also constitutes PJC Pdf/58 within personal website as item 4.3.9. [Items 4.3.6 and 4.3.7 have earlier meditations on the same theme].

2 M. Lilla, The Once and Future Liberal: After Identity Politics, London, Hurst & Co., 2018; A. Stoker, Taking Back Control: Restoring Universalism in the Age of Identity Politics, Sydney, NSW, Centre for Independent Studies, 2019; T.B. Dyrberg, Radical Identity Politics: Beyond Right and Left, Newcastle upon Tyue, Cambridge Scholars, 2020.

3 Words from the hymn Amazing Grace (written 1772; published 1779) by John Newton (1725-1807), reflecting the personal experience of this former slave-trader turned evangelical Christian clergyman and abolitionist.

4 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proud_Boys.

5 C. Brontë, Letter dated 16 August 1849, in M. Smith (ed.), The Letters of Charlotte Brontë, Vol. 2: 1848-51, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 235.

6 D. Parfit, Reasons and Persons, Oxford, Clarendon, 1984; E. Sprague, Persons and their Minds: A Philosophical Investigation, London, Routledge, 2018.

7 G. Stanghellini and R. Rosfort, Emotions and Personhood: Exploring Fragility – Making Sense of Vulnerability, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2013.

8 C. Hutton, Integrationism and the Self: Reflections on the Legal Personhood of Animals, Hong Kong, Routledge, 2019.

9 E.L Graham, Making the Difference: Gender, Personhood and Theology, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

10 F. Brugère, La politique de l’individu, Paris, La République des Idées, Seuil, 2013; A. Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age, Cambridge, Polity, 1991.

11 R. Jones, Personhood and Social Robotics: A Psychological Consideration, London, Routledge, 2015.

12 J. Richardson, Freedom, Autonomy and Privacy: Legal Personhood, London, Routledge, 2015; W.A.J. Kurki, A Theory of Legal Personhood, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2019; L.M. Kingston, Fully Human: Personhood, Citizenship and Rights, New York, Oxford University Press, 2019.

13 L.P. Appell-Warren, Personhood: An Examination of the History and Use of an Anthropological Concept, Lewiston, Edwin Mellen Press, 2014.

14 P. Higgs and C. Gilleard, Personhood, Identity and Care in Advanced Old Age, Cambridge, Polity, 2016.

15 N. Makovicky, Neoliberalism, Personhood and Postsocialism: Enterprising Selves in Changing Economies, Farnham, Ashgate, 2014; reissued London, Routledge, 2016.

16 M. Lodge and C.B. Taber, The Rationalising Voter, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013; L. Mechtenberg and J-R. Tyran, Voter Motivation and the Quality of Democratic Choice, London, Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2015.

17 J.L. Gittinger, Personhood in Science Fiction: Religious and Philosophical Considerations, Cham, Switzerland, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

18 Z. Olszewska, The Pearl of Dari: Poetry and Personhood among Young Afghans in Iran, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2015.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 121 please click here