MONTHLY BLOG 99, WHY BOTHER TO STUDY THE RULEBOOK?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2019)

Joining a public committee of any kind? Before getting enmeshed in the details, I recommend studying the rulebook. Why on earth? Such advice seems arcane, indeed positively nerdy. But I have a good reason for this recommendation. Framework rules are the hall-mark of a constitutionalist culture.

|

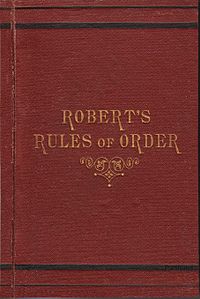

Fig.1 The handsome front cover of the first edition of Robert’s Rules of Order (1876): these model rules, based upon the practices of the US Congress, remain widely adopted across the USA, their updating being undertaken by the Robert’s Rules Association, most recently in 2011. |

Once, many years ago, I was nominated by the London education authority – then in the form of the Inner London Education Authority or ILEA – onto a charitable trust in Battersea, where I live. I accepted, not with wild enthusiasm, but from a sense of civic duty. The Trust was tiny and then did not have much money. It was rumoured that a former treasurer in the 1930s had absconded with all the spare cash. But anyway in the early 1970s the Trust was pottering along and did not seem likely to be controversial.

My experience as a Trustee was, however, both depressing and frustrating. The Trust was then named Sir Walter St. John’s Trust; and it exists today in an updated and expanded guise as the Sir Walter St. John’s Educational Charity (www.swsjcharity.org.uk). It was founded in 1700 by Battersea’s local Lord of the Manor, after whom it is named. In the 1970s, the Trust didn’t do much business at all. The only recurrent item on the agenda was the question of what to do about a Victorian memorial window which lacked a home. The fate of the Bogle Smith Window (as it was known) had its faintly comic side. Surely somewhere could be found to locate it, within one or other of the two local state-sector grammar schools, for which the Trust was ground landowner? But soon the humour of wasting hours of debate on a homeless window palled.

I also found it irksome to be treated throughout with deep suspicion and resentment by most of my fellow Trustees. They were Old Boys from the two schools in question: Battersea Grammar School and Sir Walter St. John School. All the Trust business was conducted with outward calm. There were no rows between the large majority of Old Boys and the two women appointed by the ILEA. My fellow ILEA-nominee hardly ever attended; and said nothing, when she did. Yet we were treated with an unforgiving hostility, which I found surprising and annoying. A degree of misogyny was not unusual; yet often the stereotypical ‘good old boys’ were personally rather charming to women (‘the ladies, God bless’em’) even while deploring their intrusion into public business.

But no, these Old Boys were not charming, or even affable. And their hostile attitude was not caused purely by misogyny. It was politics. They hated the Labour-run ILEA and therefore the two ILEA appointees on the Trust. It was a foretaste of arguments to come. By the late 1970s, the Conservatives in London, led by Councillors in Wandsworth (which includes Battersea) were gunning for the ILEA. And in 1990 it was indeed abolished by the Thatcher government.

More than that, the Old Boys on the Trust were ready to fight to prevent their beloved grammar schools from going comprehensive. (And in the event both schools later left the public sector to avoid that ‘fate’). So the Old Boys’ passion for their cause was understandable and, from their point of view, righteous. However, there was no good reason to translate ideological differences into such persistently rude and snubbing behaviour.

Here’s where the rulebook came into play. I was so irked by their attitude – and especially by the behaviour of the Trust’s Chair – that I resolved to nominate an alternative person for his position at the next Annual General Meeting. I wouldn’t have the votes to win; but I could publicly record my disapprobation. The months passed. More than a year passed. I requested to know the date of the Annual General Meeting. To a man, the Old Boys assured me that they never held such things, with something of a lofty laugh and sneer at my naivety. In reply, I argued firmly that all properly constituted civic bodies had to hold such events. They scoffed. ‘Well, please may I see the Trust’s standing orders?’ I requested, in order to check. In united confidence, the Old Boys told me that they had none and needed none. We had reached an impasse.

At this point, the veteran committee clerk, who mainly took no notice of the detailed discussions, began to look a bit anxious. He was evidently stung by the assertion that the Trust operated under no rules. After some wrangling, it was agreed that the clerk should investigate. At the time, I should have cheered or even jeered. Because I never saw any of the Old Boys again.

Several weeks after this meeting, I received through the post a copy of the Trust’s Standing Orders. They looked as though they had been typed in the late nineteenth century on an ancient typewriter. Nonetheless, the first point was crystal clear: all members of the Trust should be given a copy of the standing orders upon appointment. I was instantly cheered. But there was more, much more. Of course, there had to be an Annual General Meeting, when the Chair and officers were to be elected. And, prior to that, all members of the Trust had to be validly appointed, via an array of different constitutional mechanisms.

An accompanying letter informed me that the only two members of the Trust who were correctly appointed were the two ILEA nominees. I had more than won my point. It turned out that over the years the Old Boys had devised a system of co-options for membership among friends, which was constitutionally invalid. They were operating as an ad hoc private club, not as a public body. Their positions were automatically terminated; and they never reappeared.

In due course, the vacancies were filled by the various nominating bodies; and the Trust resumed its very minimal amount of business. Later, into the 1980s, the Trust did have some key decisions to make, about the future of the two schools. I heard that its sessions became quite heated politically. That news was not surprising to me, as I already knew how high feelings could run on such issues. These days, the Trust does have funds, from the eventual sale of the schools, and is now an active educational charity.

Personally, I declined to be renominated, once my first term of service on the Trust was done. I had wasted too much time on fruitless and unpleasant meetings. However, I did learn about the importance of the rulebook. Not that I believe in rigid adhesion to rules and regulations. Often, there’s an excellent case for flexibility. But the flexibility should operate around a set of framework rules which are generally agreed and upheld between all parties.

Rulebooks are to be found everywhere in public life in constitutionalist societies. Parliaments have their own. Army regiments too. So do professional societies, church associations, trade unions, school boards, and public businesses. And many private clubs and organisations find them equally useful as well. Without a set of agreed conventions for the conduct of business and the constitution of authority, there’s no way of stopping arbitrary decisions – and arbitrary systems can eventually slide into dictatorships.

As it happens, the Old Boys on the Sir Walter St. John Trust were behaving only improperly, not evilly. I always regretted the fact that they simply disappeared from the meetings. They should at least have been thanked for their care for the Bogle Smith Window. And I would have enjoyed the chance to say, mildly but explicitly: ‘I told you so!’

Goodness knows what happened to these men in later years. I guess that they continued to meet as a group of friends, with a great new theme for huffing and puffing at the awfulness of modern womanhood, especially the Labour-voting ones. If they did pause to think, they might have realised that, had they been personally more pleasant to the intruders into their group, then there would have been no immediate challenge to their position. I certainly had no idea that my request to see the standing orders would lead to such an outcome.

Needless to say, the course of history does not hinge upon this story. I personally, however, learned three lasting lessons. Check to see what civic tasks involve before accepting them. Remain personally affable to all with whom you have public dealings, even if you disagree politically. And if you do join a civic organisation, always study the relevant rulebook. ‘I tried to tell them so!’ all those years ago – and I’m doing it now in writing. Moreover, the last of those three points is highly relevant today, when the US President and US Congress are locking horns over the interpretation of the US constitutional rulebook. May the rule of law prevail – and no prizes for guessing which side I think best supports that!

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 99 please click here