MONTHLY BLOG 123, THE PEOPLING OF BRITAIN: PROPOSED SCHOOLS COURSE FOR TEENAGERS

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2021)

|

123.1 Black-and-white diagram showing ‘everyman’ and ‘everywoman’ on the move: |

Humans are a globe-trotting species;1 and the people of Britain are notable exponents of that trait. In fact, continental Europe’s sizeable offshore islands, with their long maritime tradition, are among the world’s most hybrid communities. Its people come and go. Many stop and stay. Others move on and depart, and, not infrequently, return. In the process, their histories say much about both the culturally positive and negative aspects of migration.

For that reason, there’s a great case for a schools course for British teenagers to study ‘The Peopling of Britain’, from the earliest times until now. Everybody’s family plays a part in the collective story. Such a course can be located within Modern History, or Sociology, or Civics: and it can easily be associated with individual Roots Projects, in which students discuss their history with older members of the family.2

Such themes need to be addressed with care and sensitivity. Not all families are happy to uncover past secrets, if secrets there be. Some are happy to be revealed as ‘stayers’. Yet not all families are satisfied with staying put. Conversely, not all cases of migration are happy ones. And some adopted children don’t know their full family history. They especially need thoughtful and sensitive help in tracing their roots, in so far as that’s possible.3 But they can also benefit from understanding their adoptive families’ stories, which show how population mixing happens from day-to-day, as part of ordinary life. These are all crucial issues for young adults as they grow up and find their places in a complex society. So it is helpful to confront the long history of ‘the peopling of Britain’ in a supportive class environment, with supportive teachers.

One immediate effect is to provide historical perspective. Population movement into and out of Britain is far from a recent invention. It goes back to the very earliest recorded settlements by Celts and Basques; and has continued ever since. In 1701 the novelist and journalist Daniel Defoe amused his readers by poetically lampooning the mongrel heritage of The True-Born Englishman:

‘The Scot, Pict, Britain, Roman, Dane, submit;

And with the English-Saxon all Unite.’4

He was not intent on disparagement. On the contrary, he was glorying in the country’s diversity. Moreover, Defoe was writing about the English as they had recruited population in the millennia before 1066. After that date, the Norman French invaders followed in 1066, Dutch and Walloon religious refugees arrived in the sixteenth century; French Huguenot, German, Irish, and Caribbean migrants settled from the eighteenth century onwards; and many others have followed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, from Canada, North and South America; from the Middle East; from India, Pakistan, China, and the Far East, including the Philippines; from many parts of Africa; from Australia and New Zealand; as well as from Scandinavia, from across central, southern and eastern Europe – and, on a small scale, from Russia.5

Defoe’s point, as he explained in the Preface to the 1703 edition of The True-Born Englishman, was that population migration was and is normal. Accordingly, he explained that: ‘I only infer, that an English Man, of all Men ought not to despise Foreigners as such, and I think the Inference is just, since what they are today, we were yesterday; and tomorrow they will be like us’.6

Of course, migration has not always been easy. That is a big, obvious and important point. There have been tensions, hostilities, riots, rejection, and simmering bitterness.7 But such responses should not therefore be brushed under the historical carpet. Instead, it is helpful for students to explore: why tensions emerge in some circumstances; and not in others. And in some periods; but not in others? What factors help integration? And which factors impeded cohesion? The answers include crucial contextual factors, like the availability of work and housing. And they also highlight the behaviour both of host communities and of migrant groups, including rival languages, religions, and differing cultural attitudes – for example to the role of women.

At the same time, migration has its positive and dynamic side. The acceptance of social pluralism, for example with different religions worshipping peacefully side by side, is a useful civic art, in a world full of different religious groups. Equally, learning from and sharing the global diversity of food and music adds much to cultural creativity. And the same applies across the board, in terms of generating and sharing the global stock of knowledge, to which all cultures contribute.

Moreover, there is one quietly successful – almost secret – experience that underpins migration, which many students’ own family histories will reveal. That is, the very great extent of intermarriage between these migrant groups, especially over time. (Needless to say, not all the unions between people from different backgrounds were actually legal ones; but ‘intermarriage’ is the demographers’ term not just for sexual encounters but for all unions which produced children). Such relationships happen across and between different ethnic, religious, and social groups, even when forbidden. Romeo and Juliet are the tragic theatrical representations of a human story of love despite barriers.

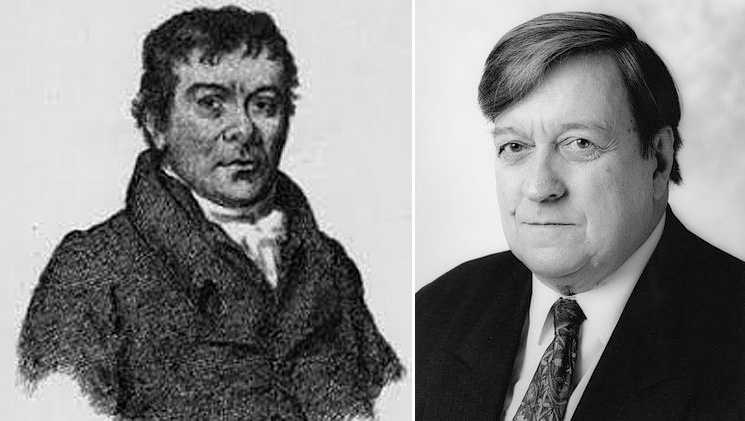

It is certainly a common experience for Britons, who delve back into their ancestry, to find forebears from a variety of ethnic, religious and geographical origins. Equally, many known migrants to Britain from ‘foreign parts’ have descendants who merge seamlessly into the population today. One example stands proxy for many. The ancestry of Lord ‘Bill’ Wedderburn, a noted Labour lawyer and politician (1927-2012), stretches back, on his father’s side, to Robert Wedderburn, the Jamaican-born radical and anti-slavery campaigner (1762-c.1835). They couldn’t meet in daily life; but they do meet in the pages of British history – complete with their intent gazes and small frown lines between the eyes.

|

123.2 (L) Jamaican-born Robert Wedderburn (1762-c.1835), anti-slavery campaigner, and (R) his descendant, Bill Wedderburn, lawyer & Labour politician (1927-2012). |

Incidentally, Britain’s long-standing aversion to national identity papers made it hard for the authorities in earlier times to track the location of migrants. Hence many ‘foreigners’ quietly Anglicised their names and disappeared from the official record. That situation contrasted, for example, with non-Islamic newcomers into the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire. They were required, in theory at least, to wear distinctive dress, featuring specifically coloured turbans to indicate their religious/ethnic origins.8 But all such regulations were difficult to sustain over time, as migrant families became established over successive generations.

Studying these issues provides a long-term perspective on issues of social and personal sensitivity. The Schools’ curriculum tends to be divided into chunks around specific periods of history – often very recent ones. But it’s good for teenagers to study some long-term trends. History is rightly not taught today as one inevitable success story. Old Whig views of ‘the March of Progress’ have been discarded in the light of chronic warfare, famines, genocides, racism, chronic poverty, and sundry catastrophes. And an alternative Marxist view of history as unending class struggle, leading to the inevitable triumph of the proletariat, has also been revealed as a massive over-simplification.9

Yet all British students can study with benefit the long-term peopling of the country in which they live. They will confront conflict, but also cooperation. Enmities but also love. They will learn how and why people move – and how societies can learn to cope with migration. These complex legacies impact not only upon society at large but also upon all individuals. (At the same time, too, there is a parallel story of the massive British diaspora around the world).10 Understanding the history of humanity’s chronic globe-trotting is part of learning to be simultaneously a British citizen and a global one.

ENDNOTES:

1 L.L. Cavalli-Sforza and F. Cavalli-Sforza, The Great Human Diasporas: The History of Diversity and Evolution, transl. S. Thomas (Harlow, 1995).

2 See companion-piece PJC BLOG/122 (Feb.2021), ‘Proposed Roots Project for Teenagers’. And relevant analysis in R. Coleman, ‘Why We Need Family History Now More than Ever’, FamilySearch, 26 Sept. 2017: https://www.familysearch.org/blog/en/family-history-2.

3 See e.g. J. Rees, Life Story Books for Adopted Children: A Family-Friendly Approach (2009); J. Waterman and others, Adoption-Specific Therapy: A Guide to Helping Adopted Children and their Families Thrive (Washington DC, 2018); A. James, The Science of Parenting Adopted Children: A Brain-Based, Trauma-Informed Approach to Cultivating Your Child’s Social, Emotional and Moral Development (2019).

4 D. Defoe, The True-Born Englishman (1703), lines 25-26.

5 J. Walvin, Passage to Britain: Immigration in British History and Politics (Harmondsworth, 1984); P. Panayi, An Immigration History of Britain: Multicultural Racism since 1800 (Harlow, 2010); M. Spafford and D. Lyndon, Migrants to Britain, c.1250 to Present (2016).

6 Defoe, True-Born Englishman, Preface to 1703 edn.

7 A.H. Richmond, Immigration and Ethnic Conflict (Basingstoke, 1988); R.M. Dancygier, Immigration and Conflict in Europe (Cambridge, 2010).

8 D. Quataert, ‘Clothing Laws, State and Society in the Ottoman Empire, 1720-1829’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 29 (1997), pp. 403-25.

9 P.J. Corfield, Time and the Shape of History (2007), pp. 74-5, 174-8; and idem, ‘Time and the Historians in the Age of Relativity’, in A.C.T. Geppert and Till Kössler (eds), Obsession der Gegenwart: Zeit im 20. Jahrhundert; transl. as Obsession with the Here-and-Now: Concepts of Time in the Twentieth Century, (Göttingen, 2015), pp. 71-91, esp. pp. 78-80, 83.

10 E. Richards, Britannia’s Children: Emigration from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland since 1600 (2004).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 123 please click here