MONTHLY BLOG 29, SHOULD EACH SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION REWRITE THE UK SCHOOLS HISTORY SYLLABUS?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2013)

The answer is unequivocally No. (Obvious really but worth saying still?)

History as a subject is far, far too important to become a political football. It teaches about conflict as well as compromise; but that’s not the same as being turned into a source of conflict in its own right. Direct intervention by individual politicians in framing the History syllabus is actively dangerous.

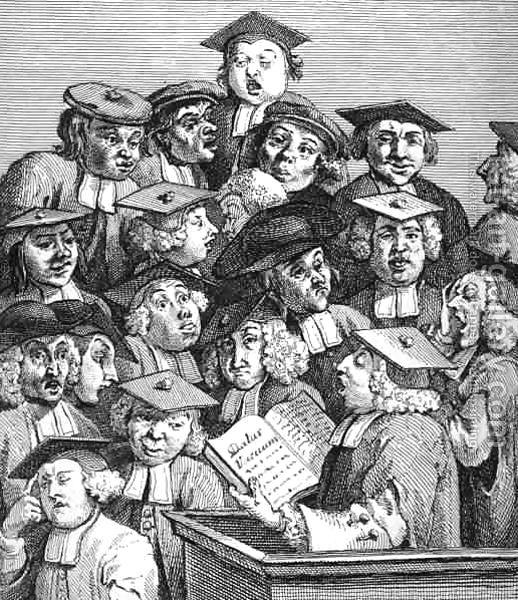

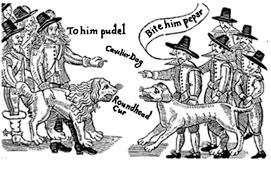

| Rival supporters of King and Parliament in the 1640s civil wars, berating their opponents as ‘Roundhead curs’ and ‘Cavalier dogs’: the civil wars should certainly appear in the Schools History syllabus but they don’t provide a model for how the syllabus should be devised. |

There are several different issues at stake. For a start, many people believe that the Schools curriculum, or prescriptive framework, currently allots too little time to the study of History. There should be more classes per week. And the subject should be compulsory to the age of sixteen.1 Those changes would in themselves greatly enhance children’s historical knowledge, reducing their recourse to a mixture of prevalent myths and cheerful ignorance.

A second issue relates to the balance of topics within the current History syllabus, which specifies the course contents. I personally do favour some constructive changes. There is a good case for greater attention to long-term narrative frameworks,2 alongside high-quality in-depth studies.

But the point here is: who should actually write the detailed syllabus? Not individual historians and, above all, not individual politicians. However well-intentioned such power-brokers may or may not be, writing the Schools History syllabus should be ultra-vires: beyond their legal and political competence.

The need for wide consultation would seem obvious; and such a process was indeed launched. However, things have just moved into new territory. It is reported that Education Secretary has unilaterally aborted the public discussions. Instead, the final version of the Schools History syllabus, revealed on 7 February 2013, bears little relation to previous drafts and discussions.3 It has appeared out of the (political) blue.

Either the current Education Secretary acted alone, or perhaps had some unnamed advisers, working behind the scenes. Where is the accountability in this mode of procedure? Even some initial supporters of syllabus revision have expressed their dismay and alarm.

Imagine what Conservative MPs would have said in 2002 if David Blunkett (to take the best known of Blair’s over-many Education Ministers) had not only inserted the teaching of Civics into the Schools curriculum as a separate subject;4 but had written the Civics syllabus as well. Or if Blunkett had chosen to rewrite the History syllabus at the same time?

Or imagine what Edmund Burke, the apostle of moderate Toryism, would have said. This eighteenth-century politician-cum-political theorist, who was reportedly identified in 2008 as ‘the greatest conservative ever’ by the current Education Secretary,5 was happy to accept the positive role of the state. Yet he consistently warned of the dangers of high-handed executive power. The authority of central government should not be untrammelled. It should not be used to smash through policies in an arbitrary manner. Instead Burke specifically praised the art of compromise or – a better word – of mutuality:

All government, indeed every human benefit and enjoyment, every virtue, and every prudent act, is founded on compromise and barter.6

An arbitrary determination of the Schools History syllabus further seems to imply that the subject not only can but ought to be moulded by political fiat. Such an approach puts knowledge itself onto a slippery slope. ‘Fixing’ subjects by political will (plus the backing of the state) leads to intellectual atrophy.

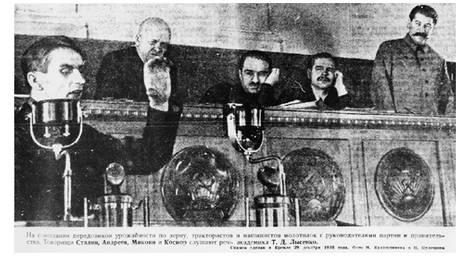

To take a notoriously extreme example, Soviet biology was frozen for at least two generations by Stalin’s doctrinaire endorsement of Lysenko’s environmental genetics.7 A dramatic rise in agrarian productivity was promised, without the need for fertilisers (or more scientific research). Stalin was delighted. Down with the egg-heads and their slow research. Lysenko’s critics were dismissed or imprisoned. But Lysenkoism did not work. And, after unduly long delays, his pseudo-science was finally discredited.

| A rare photo of Stalin (back R) gazing approvingly at Trofim Lysenko (1898-1976) speaking from the rostrum in the Kremlin, 1935 |

In this case, the Education Secretary is seeking to improve schoolchildren’s minds rather than to improve crop yields. But declaring the ‘right’ answer from the centre is no way to achieve enlightenment. Without the support of the ‘little platoons’ (to borrow another key phrase from Burke), the proposed changes may well prove counter-productive in the class-room. Many teachers, who have to teach the syllabus, are already alienated. And, given that History as a subject lends itself to debate and disagreement, pupils will often learn different lessons from those intended.

Intellectual interests in an Education Secretary are admirable. The anti-intellectualism of numerous past ministers (including too many Labour ones) has been horribly depressing. But intellectual confidence, tipped into arrogance, can be taken too far. Another quotation to that effect is often web-attributed to Edmund Burke, though it seems to come from Albert Einstein. He warned that powerful people should wisely appreciate the limits of their power:

Whoever undertakes to set himself up as a judge of Truth and Knowledge is shipwrecked by the laughter of the gods.8

1 That viewpoint was supported in my monthly BLOG no.23 ‘Why do Politicians Undervalue History in Schools’ (Oct. 2012): see www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk.

2 I proposed a long-span course on ‘The Peopling of Britain’ in History Today, 62/11 (Nov. 2012), pp. 52-3.

3 See D. Cannadine, ‘Making History: Opportunities Missed in Reforming the National Curriculum’, Times Literary Supplement, 15 March 2013, pp. 14-15; plus further responses and a link to the original proposals in www.historyworks.tv

4 For the relationships of History and Civics, see my monthly BLOG no.24 ‘History as the Staple of a Civic Education’, www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk.

5 Michael Gove speech to 2008 Conservative Party Annual Conference, as reported in en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Gove, consulted 3 April 2013.

6 Quotation from Edmund Burke (1729-97), Second Speech on Conciliation with America (1775). For further context, see D. O’Keeffe, Edmund Burke (2010); I. Kramnick, The Rage of Edmund Burke: Portrait of an Ambivalent Conservative (New York, 1977); and F. O’Gorman (ed.), British Conservatism: Conservative Thought from Burke to Thatcher (1986).

7 Z. Medvedev, The Rise and Fall of T.D. Lysenko (New York, 1969).

8 Albert Einstein (1879-1955), in Essays Presented to Leo Baeck on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday (1954), p. 26. The quotation is sometimes (but wrongly) web-attributed to Edmund Burke’s critique of Jacobin arrogance in his Preface to Brissot’s Address to his Constituents (1794).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 29 please click here