MONTHLY BLOG 21, HISTORICAL PERIODISATION – PART 1

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2012)

It was fascinating to meet with twenty-three others on a humid June afternoon to debate what might appear to be abstruse questions of Law & Historical Periodisation. We were attending a special conference at Birkbeck College, London University – an institution (founded in 1823 as the London Mechanics Institute) committed as always to extending the boundaries of knowledge. The participants came from the disciplines of law, history, philosophy, and literary studies. And many were students, including, laudably, some interested undergraduates who were attending in the vacation.

At stake was not the question of whether we can generalise about different and separate periods of the past. Obviously we can and must to some extent. Even the most determined advocate of history as ‘one and indivisible’ has to accept some sub-divisions for operative purposes, whether in terms of days, years, centuries or millennia.

But the questions really coalesce about temporal ‘stages’, such as the ‘mediaeval’ era. Are such concepts relevant and helpful? Is history rightly divided into successive stages? and do they follow in regular sequence in different countries, even if at different times? Or is there a danger of reifying these epochs – turning them into something more substantive and distinctive than was actually the case?

Studies like H.O. Taylor’s The Medieval Mind (1919 and many later edns), Benedicta Ward’s Miracles and the Medieval Mind (1982), William Manchester’s The Medieval Mind and the Renaissance (Boston, 1992), and Stephen Currie’s Miracles, Saints and Superstition: The Medieval Mind (2006), all imply that there were common properties to the mind-sets of millions of Europeans who lived between (roughly) the fifth-century fall of Rome and the fifteenth-century discovery of the New World – and that these mindsets differed sharply from the ‘modern mind’. Yet are these historians justified in choosing this formula within their titles? Or partly justified? or absolutely misleading? Are there common features within human consciousness and experiences that refute these periodic cut-off points? Do we want to go to the other end of the spectrum, to endorse the view of those Evolutionary Psychologists who aver that human mentalities have not changed since the Stone Age? Forever he, whether Tarzan, Baldric or Kevin? forever she, whether Jane, Elwisia or Tracey?

Two papers by Kathleen Davis (University of Rhode Island) and Peter Fitzpatrick (Birkbeck College) formed the core of the conference, both focusing upon the culture of jurisprudence and its standard definition of the medieval. Both give stimulating critiques of conventional legal assumptions, based upon stark dichotomies. In bare summary, the ‘medieval’ is supposed to be Christianised, feudal, and customary, while the ‘modern’ is supposedly secular, rights-based, and centred around the sovereign state. For good measure, the former is by implication backward and oppressive, while the latter is progressive and enlightened. Yet the long history of legal pluralism goes against any such dichotomy in practice. Historians like Helen Cam, who in 1941 wrote What of Medieval England is Alive in England Today? would have rejoiced at these papers, and at the sharp questions from the conference participants.

For my part, I was asked to give a final summary, based upon my position as a critic of all simple stage theories of history.1 My first point was to stress again how difficult it is to rethink periodisation, because so many cardinal assumptions are built not only into academic language but also into academic structures. Many specialists name themselves after their periods – as ‘medievalists’, ‘modernists’ or whatever. Those who call themselves just ‘historians’ are seen as too vague – or suffering from folie de grandeur. There are mutterings about the fate of Arnold Toynbee, once hailed as the twentieth-century’s greatest historian-philosopher – now virtually forgotten. Academic posts within departments of History and Literary Studies are generally defined by timespans. So are examination papers; many academic journals; many conferences; and so forth. Publishers in particular, who pay great attention to book titles, often endorse traditional nomenclature and stage divisions.

True, there are now increasing calls for change. My second point therefore highlights the new diversity. Conferences and seminars are held not only across disciplinary boundaries but also across epochal divisions. An increasing number of books are published with unusual start and end dates; and the variety of dates attached to the traditional periods continues to multiply, often confusingly. In addition, some scholars now study ‘big’ (long-term) history from the start of the world, or at least from the start of human history. Their approaches do not always manage to avoid traditional schema but the aim is to encourage a new diachronic sweep. And other pressures for change are coming from scholars in new fields of history, such as women’s history or (not the same thing) the history of sexuality.

Shedding the old period terminology is mentally liberating. So the Italian historian Massimo Montanari, previously a ‘medievalist’, wrote in 1994 of the happiness that followed his discarding of all the labels of ‘ancient’, ‘medieval’ and ‘modern: ‘In the end, I felt freed as from a restrictive and artificial scaffolding …’2

Lastly, then, what of the future? The aim is not to replace one set of period terms and dates with another. Any rival set will run into the same difficulties of detecting precise cut-off points and the risk of stereotyping the different cultures and societies on either side of a period boundary. It is another example of dichotomous thinking, which glosses over the complexities of the past. Above all, all stage theories fail to incorporate the elements of deep continuity within history (see my November 2010 discussion-point).

We need a new way of thinking about the intertwining of persistence and change within history. It is chiefly a matter of understanding. But it will also entail a change of language. I don’t personally endorse the Foucauldian view that language actually determines consciousness. For me, primacy in the relationship is the other way round. A changing consciousness can ultimately change language. Yet I do recognise the confining effects of existing concepts and terminology upon patterns of thought. Such an impact is another example of the power of continuity. With several bounds, however, historians can become free. With a new language, we can talk about epochs and continuities, intertwined and interacting in often changing ways. It’s fun to try and also fun to try to convince others. Medievalists, arise. You have nothing to lose but an old name, which survives through inertia. There are more than three steps between ancient – middle – modern, even in European history – let alone around the world. Try a different name to shake the stereotypes. And tell the lawyers too.

1 P.J. Corfield, Time and the Shape of History (2007) and P.J. Corfield, POST-Medievalism/ Modernity/ Postmodernity? Rethinking History, Vol. 14/3 (Sept. 2010), pp. 379-404; also available on publishers’ website Taylor & Francis www.tandfonline.com; and personal website www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk.

2 M. Montanari, The Culture of Food (transl. C. Ipsen (Oxford, 1994), p. xii.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 21 please click here

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone.

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone. And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator.

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator. So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury.

So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury. In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4

In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4

Secondly: political revolutions also need to be located within a spectrum of different sorts and degrees of change. It is very rarely, if ever, that everything is transformed all at once. The rhetoric of dramatic metamorphosis is both fearful and hopeful: ‘All changed, changed utterly;/ A terrible beauty is born’, as Yeats saluted the Irish Easter Rising in 1916. Yet, when the dust dies down, continuity turns out to have dragged at the heels of revolution after all. What is known as admirable heritage to its fans is deplorable inertia to its critics. Thus Karl Marx once denounced with righteous passion: ‘the tradition of all the dead generations [that] weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’.

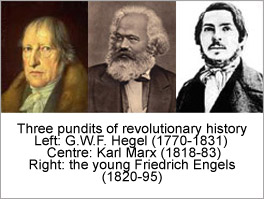

Secondly: political revolutions also need to be located within a spectrum of different sorts and degrees of change. It is very rarely, if ever, that everything is transformed all at once. The rhetoric of dramatic metamorphosis is both fearful and hopeful: ‘All changed, changed utterly;/ A terrible beauty is born’, as Yeats saluted the Irish Easter Rising in 1916. Yet, when the dust dies down, continuity turns out to have dragged at the heels of revolution after all. What is known as admirable heritage to its fans is deplorable inertia to its critics. Thus Karl Marx once denounced with righteous passion: ‘the tradition of all the dead generations [that] weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’. Yet no. Not only does fundamental change frequently develop via evolutionary rather than revolutionary means; but revolutions do not always introduce macro-change. They can fail, abort, halt, recede, fudge, muddle, diverge, transmute and/or provoke counter-revolutions. The complex failures and mutations of the communist revolutions, which were directly inspired in the twentieth century by the historical philosophy of Marx and Engels, make that point historically, as well as theoretically.

Yet no. Not only does fundamental change frequently develop via evolutionary rather than revolutionary means; but revolutions do not always introduce macro-change. They can fail, abort, halt, recede, fudge, muddle, diverge, transmute and/or provoke counter-revolutions. The complex failures and mutations of the communist revolutions, which were directly inspired in the twentieth century by the historical philosophy of Marx and Engels, make that point historically, as well as theoretically.

Lastly, for historians, it is also not surprising to find that gradual change is a powerful force in human history. There are many long-term trends that are slow and relatively imperceptible at the time. One example is the world-wide spread of literacy since circa 1700. Certainly there have been oscillations in the trend; but it is unlikely to be reversed, short of global catastrophe.

Lastly, for historians, it is also not surprising to find that gradual change is a powerful force in human history. There are many long-term trends that are slow and relatively imperceptible at the time. One example is the world-wide spread of literacy since circa 1700. Certainly there have been oscillations in the trend; but it is unlikely to be reversed, short of global catastrophe.

Of course, Karr was not completely right. Changes undoubtedly do happen, both gradually and dramatically. But they are always tempered by the power of Continuity. In fact, innovations may fail or prove to be counterproductive – either because opponents consciously strive to circumvent change – or because the innovations are imperfectly planned and/or implemented – or because the innovations have anyway little intrinsic chance of success.

Of course, Karr was not completely right. Changes undoubtedly do happen, both gradually and dramatically. But they are always tempered by the power of Continuity. In fact, innovations may fail or prove to be counterproductive – either because opponents consciously strive to circumvent change – or because the innovations are imperfectly planned and/or implemented – or because the innovations have anyway little intrinsic chance of success.