MONTHLY BLOG 32, REACTIONS TO MAKING A HISTORY DVD

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2013)

Having made the hour-long History DVD Red Battersea 1809-2008 (2008), what reactions did we get? The production team quickly became aware that Battersea CLP, among all Britain’s local constituency parties of all political persuasions, has done something unique. We’ve written a collective autobiography in mid-life, as it were. And we have done so on DVD, integrally combining script with images.

Since launching the DVD into the world, we are often asked not why we did it – but how? In response, a small panel of Battersea members have given DVD showings to other Labour constituency parties, to student film societies, to local community groups, to Heritage associations, and to academics, who are interested in twentieth-century social and electoral history. Attention is focused upon the technical as well as the intellectual challenges of constructing a filmic narrative from a mixture of research, images, beliefs, and memories. Here follow the discussion-points about sound and images that audiences often raise:

Voices: Why did we choose to tell the story in many voices rather than via one main narrator? The DVD uses a collage of voices from unseen narrators, led by the utterly distinctive voice of actor Timothy West. But he does not hog the soundwaves. We have a plurality of voices, some from professional actors and many from the Battersea community. Each narrator picks up the baton seamlessly, but some figure as witnesses, hence speaking as themselves. Even in those cases, I wrote their scripts, in order to avoid the ‘ums’ and ‘ahs’ of real-life diction and to keep their remarks brisk. I did, however, write all such individual statements very carefully, following my witnesses’ natural speech cadences in the prior interviews.

As a result, the DVD does not have one lead narrator who keeps striding into and out of the frame, blocking the view of the historical evidence. That style has been fashionable for many years. Look at very many TV history series – and the Labour Party’s own Party history, which features Tony Benn. The aim of using a lead narrator is to familiarise and personalise. But the style can quickly become dated and liable to parody. Moreover, details of the narrator’s clothing, expressions, hair-styles, and body language can easily distract viewers, both first time round and then on later reruns, from the history that is being shown over the narrator’s shoulder. By no means everyone agrees. In my personal view, however, the narrator-striding-into-camera technique will eventually become obsolete – but perhaps not quite yet.

In contrast, expressive voices, blended together from unseen narrators, remain much more timeless. For my purposes, they also give a fair evocation of a collective movement. It is true that one or two of our local volunteers found it hard to sound natural when recording. Chronic mumblers had to be excluded. But most speakers took to the task very readily and, if they fluffed the first take, were happy to try again. Bearing in mind the need for clear communication, I had tried hard to make the script ‘read-aloud-able’.

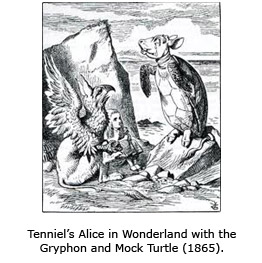

One of our Battersea professional actors Su Elliott gives great advice on voice production for radio. Mimic the emotions with the face, even while unseen, she counsels. As one of our travelling panellists, she sobs convulsively in the character of the Mock Turtle, while giving as great a visual look of Lewis Carroll’s (and Tenniel’s) doleful beast as anyone could wish – always to much audience appreciation. Actually, none of our DVD speakers had to be that sad, even when Battersea Labour has to admit to reverses and failures during its more than hundred-year history. We are here for the long term – and march on!

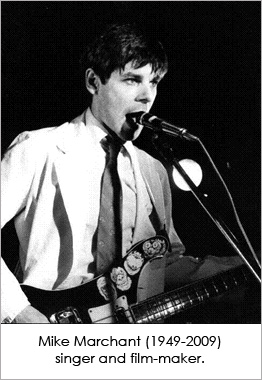

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide.

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide.

The question, however, that most intrigues our DVD viewers is not where we found the material but how we continually matched the flow of images to the flow of the script. When making a film, the two go seamlessly together, although both can be retouched later. But a DVD works by aligning a sound-track to a vision-track. Each can be worked on separately. Quite a different production style.

My July BLOG has already explained the no-doubt obvious point to the technically-minded – that the sound-track takes the lead, because it sets the crucial time parameters. The images then followed, many being researched to order. Mike Marchant would telephone saying: ‘Hello, I need two minutes worth of visuals on XXX’. After an initial feeling of exasperation (‘No, I don’t think about history like that’), I would respond more calmly: ‘What images would help viewers to get the point, especially if it is an abstract one?’ Often we sorted things immediately. At other moments, we struggled. Throughout, Mike and I strove for variety within our house-style, using a range of images (photos, film clips, video footage, texts, captions) to prevent a feeling of sameness.

Trying for visual diversity was good fun, especially for me. Eagerly but amateurishly, I would request various film manoeuvres (zoom, fade, etc), while Mike had the hard work of achieving that effect without the full panoply of film cameras, sound technicians, lighting engineers and so forth. I often felt guilty when he later revealed the time it took to respond to each casual request; but I’m sure ultimately that he enjoyed the challenge.

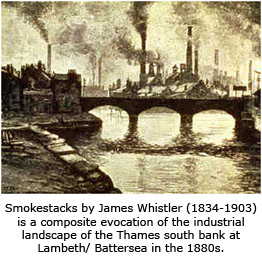

What struck me most was the vivid realisation of how easily, in a DVD production, the story can be made or marred by the alignment/ non-alignment of the image- and sound-tracks. We tried not to be too literal. Viewers don’t need to see an industrial plant every time we mention the heavy industries that used to line the Battersea river-front. It’s patronising to assume that people have no visual memory-banks of their own. Even a picture as striking as Whistler’s Smokestacks needs to appear just at the right moment.

On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’.

On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’.

So Mike Marchant and I spent ages together on fine-tuning the synchronisation. Generally, we managed to hide the late changes; but alert listeners to the DVD sound-track can pick up one or two jumps in continuity that we couldn’t conceal. Damn!

Finally, questions about bias. How can Battersea Labour present its own history without excessive political bias? How can individuals in our research team study their own political pasts without personal bias? Did our answers on those big questions satisfy our audiences? We also get asked: What’s next from Battersea Labour? There’s so much to say on all those points, that I’m keeping my answers for later BLOGs.

Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton = .

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 32 please click here

But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort.

But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort. The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends).

The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends). Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =

Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =