MONTHLY BLOG 30, BUT PEOPLE OFTEN ASK: HISTORY IS REALLY POLITICS, ISN’T IT? SO WHY SHOULDN’T POLITICIANS HAVE THEIR SAY ABOUT WHAT’S TAUGHT IN SCHOOLS?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2013)

Two fascinating questions, to which my response to the first is: No – History is bigger than any specific branch of knowledge – it covers everything that humans have done, which includes lots besides Politics. Needless to say, such a subject lends itself to healthy arguments, including debates about ideologically-freighted religious and political issues.

But it would be dangerous if the study of History were to be forced into a strait-jacket by the adherents of particular viewpoints, buttressed by power of the state. (See my April 2013 BLOG). By the way, the first question can also be differently interpreted to ask whether all knowledge is really political? I return to that subtly different issue below.*

Meanwhile, in response to the second question: I agree that politicians could do with saying and knowing more about History. Indeed, there’s always more to learn. History is an open-ended subject, and all the better for it. Because it deals with humans in ever-unfolding Time, there is always more basic data to incorporate. And perspectives upon the past can gain significant new dimensions when reconsidered in the light of changing circumstances.

Yet the case for an improved public understanding of History is completely different from arguing that each incoming Education Secretary should re-write the Schools’ History syllabus. Politicians are elected to represent their constituents and to take legislative and executive decisions on their behalf – a noble calling. In democracies, they are also charged to preserve freedom of speech. Hence space for public and peaceful dissent is supposed to be safeguarded, whether the protesters be many or few.

The principled reason for opposing attempts at political control of the History syllabus is based upon the need for pluralism in democratic societies. No one ‘side’ or other should exercise control. There is a practical reason too. Large political parties are always, whether visibly or otherwise, based upon coalitions of people and ideas. They do not have one ‘standard’ view of the past. In effect, to hand control to one senior politician means endorsing one particular strand within one political party: a sort of internal warfare, not only against the wider culture but the wider reaches of his or her own political movement.

When I first began teaching, I encountered a disapproving professor of markedly conservative views. When I told him that the subject for my next class was Oliver Cromwell, he expressed double discontent. He didn’t like either my gender or my politics. He thought it deplorable that a young female member of the Labour party, and an elected councillor to boot, should be indoctrinating impressionable students with the ‘Labour line on Cromwell’. I was staggered. And laughed immoderately. Actually, I should have rebuked him but his view of the Labour movement was so awry that it didn’t seem worth pursuing. Not only do the comrades constantly disagree (at that point I was deep within the 1971 Housing Finance Act disputes) but too many Labour activists show a distressing lack of interest in History.

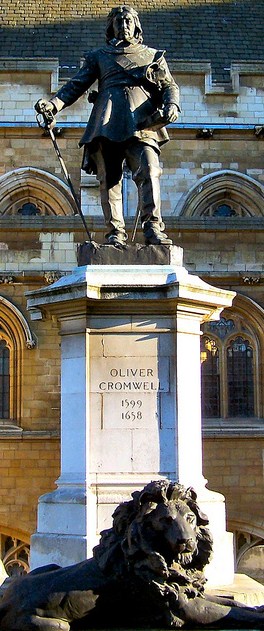

Moreover, Oliver Cromwell is hard to assimilate into a simplistic narrative of Labour populism. On the one hand, he was the ‘goodie’ who led the soldiers of the New Model Army against an oppressive king. On the other hand, he was the ‘baddie’ who suppressed the embryonic democrats known as the Levellers and whose record in Ireland was deeply controversial. Conservative history, incidentally, has the reverse problem. Cromwell was damned by the royalists as a Regicide – but simultaneously admired as a successful leader who consolidated British control in Ireland, expanded the overseas empire, and generally stood up to foreign powers.1

Interestingly, the statue of Oliver Cromwell, prominently sited in Westminster outside the Houses of Parliament, was proposed in 1895 by a Liberal prime minister (Lord Rosebery), unveiled in 1899 under a Conservative administration, and renovated in 2008 by a Labour government, despite a serious proposal in 2004 from a Labour backbencher (Tony Banks) that the statue be destroyed. As it stands, it highlights Cromwell the warrior, rather than (say) Cromwell the Puritan or Cromwell the man who brought domestic order after civil war. And, at his feet, there is a vigilant lion, whose British symbolism is hard to miss.2

Or take the very much more recent case of Margaret Thatcher’s reputation. That is now beginning its long transition from political immediacy into the slow ruminations of History. Officially, the Conservative line is one of high approval, even, in some quarters, of untrammelled adulation. On the other hand, she was toppled in 1990 not by the opposition party but by her own Tory cabinet, in a famous act of ‘matricide’. There is a not-very concealed Conservative strand that rejects Thatcher outright. Her policies are charged with destroying the social cohesion that ‘true’ conservatism is supposed to nurture; and with strengthening the centralised state, which ‘true’ conservatism is supposed to resist.3 Labour’s responses are also variable, all the way from moral outrage to political admiration.

Either way, a straightforward narrative that Thatcher ‘saved’ Britain is looking questionable in 2013, when the national economy is obstinately ‘unsaved’. It may be that, in the long term, she will feature more prominently in the narrative of Britain’s conflicted relationship with Europe. Or, indeed, as a janus-figure within the slow story of the political emergence of women. Emmeline Pankhurst (below L) would have disagreed with Thatcher’s policies but would have cheered her arrival in Downing Street. Thatcher, meanwhile, was never enthusiastic about the suffragettes but never doubted that a woman could lead.4

Such meditations are a constituent part of the historians’ debates, as instant journalism moves into long-term analysis, and as partisan heat subsides into cooler judgment. All schoolchildren should know the history of their country and how to discuss its meanings. They should not, however, be pressurised into accepting one particular set of conclusions.

I often meet people who tell me that, in their school History classes, they were taught something doctrinaire – only to discover years later that there were reasonable alternatives to discuss. To that, my reply is always: well, bad luck, you weren’t well taught; but congratulations on discovering that there is a debate and deciding for yourself.

Even in the relatively technical social-scientific areas of History (such as demography) there are always arguments. And even more so in political, social, cultural, and intellectual history. But the arguments are never along simple party-political lines, because, as argued above, democratic political parties don’t have agreed ‘lines’ about the entirety of the past, let alone about the complexities of the present and recent-past.

Lastly * how about broadening the opening question? Is all knowledge, including the study of History, really ‘political’ – not in the party-political sense – but as expressing an engaged worldview? Again, the answer is No. That extended definition of ‘political’ takes the term, which usefully refers to government and civics, too far.

Human knowledge, which does stem from, reflect and inform human worldviews, is hard gained not from dogma but from research and debate, followed by more research and debate. It’s human, not just political. It’s shared down the generations. And between cultures. That’s why it’s vital that knowledge acquisition be not dictated by any temporary power-holders, of any political-ideological or religious hue.

1 Christopher Hill has a good chapter on Cromwell’s Janus-faced reputation over time, in God’s Englishman: Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution (1970), pp. 251-76.

2 Statue of Cromwell (1599-1658), erected outside Parliament in 1899 at the tercentenary of his birth: see www.flickr.com, kev747’s photostream, photo taken Dec. 2007.

3 Contrast the favourable but not uncritical account by C. Moore, Margaret Thatcher, the Authorised Biography, Vol. 1: Not for Turning (2013) with tough critiques from Christopher Hitchens and Karl Naylor: see www.Karl-Naylor.blogspot.co.uk, entry for 23 April 2013.

4 Illustrations (L) photo of Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928), suffragette leader, orating in Trafalgar Square; (R) statue of Margaret Thatcher (1925-2013), Britain’s first woman prime minister (1979-90), orating in the Commons: see www.parliament.uk.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 30 please click here