MONTHLY BLOG 17, EVENTS LIVED THROUGH – PART TWO: 1971

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2012)

Can you take decisions? Including tough ones that don’t please everyone? I discovered that I can, by doing it intensively as an elected councillor. At the same time, I learned that, having made a decision, it’s important to defend it when the going gets tough. Unless it’s proven to have been a serious mistake (should be only rarely or, ideally, never) – in which case a dignified retreat is required. And it’s also vital to follow through, to ensure that policies are implemented. It turns out that lots of decisions are triumphantly made and then quietly shelved. Sometimes such a negative outcome stems from subterranean obstruction by the officers; but sometimes also from a surfeit of political decisions, made without time for consolidation.

These were some of the valuable lessons I learned as an elected Labour Councillor on the London Borough of Wandsworth in the years 1971-4.

It was a fascinating time. We had a large majority and a small dispirited Tory opposition. We were also predominantly new brooms, as many former Labour councillors did not stand again after our big local defeat in 1968. Many of my close political friends held leading posts in the Labour Group; and I became the Planning Applications supremo. Incidentally, I was never offered a bribe, despite chairing a committee that made various financially significant decisions. Labour’s new planning leaders early resolved that, when meeting with developers, those present should always include Council officers alongside councillors. It was the right decision. In particular, we were well aware that underhand kickbacks had been paid by building contractors to the previous Labour leader in Wandsworth.1 So we wanted to be not just clean but visibly so.

It was a fascinating time. We had a large majority and a small dispirited Tory opposition. We were also predominantly new brooms, as many former Labour councillors did not stand again after our big local defeat in 1968. Many of my close political friends held leading posts in the Labour Group; and I became the Planning Applications supremo. Incidentally, I was never offered a bribe, despite chairing a committee that made various financially significant decisions. Labour’s new planning leaders early resolved that, when meeting with developers, those present should always include Council officers alongside councillors. It was the right decision. In particular, we were well aware that underhand kickbacks had been paid by building contractors to the previous Labour leader in Wandsworth.1 So we wanted to be not just clean but visibly so.

Overall, the years 1971-4 became key ‘events lived through’ which influenced my outlook on life. Nothing like a bit of experience to leaven one’s theoretical stance. I learned that I can take decisions. And that, while I enjoyed the political hurly-burly in the short term, I was not cut out for a lifetime of the same.

Lots of things went well. I won’t list them all, because they are now history. But I was proud of running a sharp, questing, and efficient Planning Applications committee. We made good decisions briskly. We were not afraid to challenge the officers. But we stuck to good planning practice, engendering a great team morale which was left as a legacy.

Labour’s strategic stance also bore long-term fruits. We collectively opposed the proposed inner London motorway. It was initially supported by transport experts and by the political bigwigs of London Labour. But concerted opposition from grass-roots like us, and from Battersea’s MP Douglas Jay, ‘stopped the box’. It would have divided Battersea by a locally inaccessible motorway leading to a massive motorway ‘spaghetti’ interchange at Clapham Junction. Halting this planning monstrosity was a decisive victory that shifted inner-urban transport policy towards controlling motor traffic rather than giving it priority over homes, jobs and a pleasant local environment.

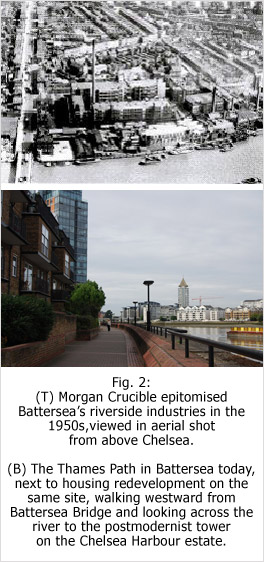

Moreover, we had many positive plans for the low-rise urban renewal of Battersea’s housing and for environmental improvements. Notably, the Wandsworth Labour councillors were among the first to promote plans for the Thames riverside walk and the Wandle walkway from Croydon to the Thames, now the Wandle Trail, supported by the Wandle Trail group. I can still remember the derision and disbelief (even on our own side) when the Planning Committee asserted that these things could and would be achieved over time. Yet the need for access to London riverfront has now become orthodoxy. The Thames River Path is not always landscaped to the best effect. But it does exist and the remaining gaps in the ‘magical 40 miles (64 km)’ from Hampton Court to the Themes Barrier are now being plugged, wherever possible.2 I still feel pride, when walking this route (see Fig.2), that I contributed to the collective effort that went into its patient creation.

Things also went wrong. The worst for the collective morale and cohesion of the Labour Group was the controversy over the Conservative government’s Housing Finance Act (1972). This legislation disempowered municipal councils of all political hues, by imposed a central decision upon local rent levels. And the Act turned out to be but the first in a long succession of moves to take power away from locally elected bodies. So we were right on democratic grounds to oppose it, in the hopes that a majority of councils would refuse to implement the act. But wrong to continue the arguments, once it was apparent that no such majority was forthcoming.1 Our Labour Group became bitterly divided. And even when we eventually agreed to implement the rent rise, we remained at odds, even while steaming ahead as a progressive Labour council. It took the gloss off what was an otherwise inspiriting experience.

Things also went wrong. The worst for the collective morale and cohesion of the Labour Group was the controversy over the Conservative government’s Housing Finance Act (1972). This legislation disempowered municipal councils of all political hues, by imposed a central decision upon local rent levels. And the Act turned out to be but the first in a long succession of moves to take power away from locally elected bodies. So we were right on democratic grounds to oppose it, in the hopes that a majority of councils would refuse to implement the act. But wrong to continue the arguments, once it was apparent that no such majority was forthcoming.1 Our Labour Group became bitterly divided. And even when we eventually agreed to implement the rent rise, we remained at odds, even while steaming ahead as a progressive Labour council. It took the gloss off what was an otherwise inspiriting experience.

After three years of intense politics, I decided – reluctantly – not to stand again. I realised that, in my core being, I was an academic, not a politician. I never regretted the decision. At the same time, my brief but intense political foray gave me respect for politicians and sympathy with the pressures of their lifestyle. Probably that’s one contributory reason for the survival of my nearly 50-year relationship with my partner Tony Belton, who has remained a Wandsworth Labour councillor since 1971.

Living with a politician, however, for me has proved enough. I’m glad that I can take decisions; and glad that one of them was to limit my experience as an elected councillor. Would I recommend this role to others? Yes, for those with time and commitment. But while for me ‘1968’ meant no instant revolution, then ‘1971’ meant no instant political solutions. I decided to remain a grass-root; and to teach/research History – not as the ‘dead past’ but as a living process.

1 In 1971, Cllr Sid Sporle was gaoled for six years on charges of corruption, having been part of a ‘building’ network including Labour’s Newcastle city boss T. Dan Smith, architect John Paulson, and Tory front-bencher Reginald Maudling. See M. Gillard, Nothing to Declare: The Political Corruptions of John Poulson (1980); Stephen Knight, The Brotherhood: The Secret World of the Freemasons (1984), pp. 203-6; and P.J. Corfield with Mike Marchant, DVD – Red Battersea: One Hundred Years of Labour, 1908-2008 (2008).

2 See David Sharp, Thames Path (National Trail Guide, 2010); and website www.walklondon.org.uk.

3 Others are writing more on this dispute. For the Derbyshire councillors who did hold out for non-implementation, to their personal cost, see J. Langdon and D. Skinner, The Story of Clay Cross (1974).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 17 please click here

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed.

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed. So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece.

So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece. For that reason, David Cameron’s slogan enrages many people, not only on the centre and left in politics, but also on the Thatcherite right, who prefer individualist rather than communal alternatives to the state. In addition, plenty of non-political grass-roots activists dislike the term too. It appears as though a currently powerful section of one political party is trying to ‘own’ the countless manifestations of community life.2

For that reason, David Cameron’s slogan enrages many people, not only on the centre and left in politics, but also on the Thatcherite right, who prefer individualist rather than communal alternatives to the state. In addition, plenty of non-political grass-roots activists dislike the term too. It appears as though a currently powerful section of one political party is trying to ‘own’ the countless manifestations of community life.2 But organic expressions of civil society began long before David Cameron invoked the ‘Big Society’ to purge the Tory’s anti-society image and will continue long after the current government has disappeared.3

But organic expressions of civil society began long before David Cameron invoked the ‘Big Society’ to purge the Tory’s anti-society image and will continue long after the current government has disappeared.3 Secondly: the pre-committed research framework. Programmes should not start by ruling out all the research options. In this case, it cannot be taken for granted that ‘the’ central state is ‘the’ problem for those seeking to build communities. Governments in contemporary societies are very variegated and diverse in their roles and structures. Their impact can in some circumstances be inimical or discouraging to community activism.

Secondly: the pre-committed research framework. Programmes should not start by ruling out all the research options. In this case, it cannot be taken for granted that ‘the’ central state is ‘the’ problem for those seeking to build communities. Governments in contemporary societies are very variegated and diverse in their roles and structures. Their impact can in some circumstances be inimical or discouraging to community activism. But it didn’t work. Long before Lysenko’s teachings were officially discredited as fraudulent in 1964, they were sidelined in practice. In wartime, Stalin learned the hard way that he had to trust his generals to fight the war. Yet he did not get the message in science, or indeed in other subjects, like history, where he intervened to support one argument as Marxist orthodoxy against another as ‘bourgeois’ revisionism. Between them, Stalin and Lysenko halted Russian biological studies and palpably harmed Soviet agriculture for over a generation, greatly weakening Soviet Russia as an international power.4

But it didn’t work. Long before Lysenko’s teachings were officially discredited as fraudulent in 1964, they were sidelined in practice. In wartime, Stalin learned the hard way that he had to trust his generals to fight the war. Yet he did not get the message in science, or indeed in other subjects, like history, where he intervened to support one argument as Marxist orthodoxy against another as ‘bourgeois’ revisionism. Between them, Stalin and Lysenko halted Russian biological studies and palpably harmed Soviet agriculture for over a generation, greatly weakening Soviet Russia as an international power.4