MONTHLY BLOG 136, A YEAR OF GEORGIAN CELEBRATIONS – 4: ENJOYING THE ANNUAL DUCK FEAST

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2022)

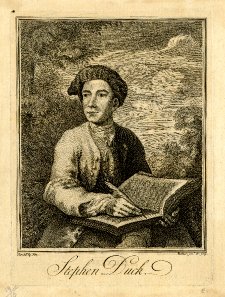

This BLOG resumes the theme of links between the Georgian era and the present.1 To do that, it takes one remarkable case-history, that of the Wiltshire poet, Stephen Duck (c.1705-56). [Yes, that was his real name] He was the son of an impoverished agricultural labourer. It’s likely that both his parents were illiterate. Yet Stephen Duck not only grew to gain poetic fame during his relatively short life but has been honoured ever since by an annual Duck Feast, held in his home village of Charlton, near Pewsey in Wiltshire.2

This BLOG resumes the theme of links between the Georgian era and the present.1 To do that, it takes one remarkable case-history, that of the Wiltshire poet, Stephen Duck (c.1705-56). [Yes, that was his real name] He was the son of an impoverished agricultural labourer. It’s likely that both his parents were illiterate. Yet Stephen Duck not only grew to gain poetic fame during his relatively short life but has been honoured ever since by an annual Duck Feast, held in his home village of Charlton, near Pewsey in Wiltshire.2

Undoubtedly, this convivial event must be the longest-running literary commemoration to be found anywhere in Britain. It is a manifestation of local community pride, as well as a tribute to creative poetic output from an obscure individual, whose merits helped him to rise in the world.

There were many such ‘shooting stars’ from modest backgrounds in eighteenth-century Britain. The expansion of towns and trade (and literacy) provided ample new opportunities for talent. Duck’s career was a classic case study in both opportunities and obstacles.

These Feasts (scheduled in early June) actually began during Duck’s lifetime. They were funded by a gift from a local bigwig, who gave a piece of land to the village in perpetuity. That provided a practical basis for the celebrations, initially confined to small numbers of men from Charlton village. A presiding host, known as the Chief Duck, welcomes guests and gives the toasts, while, over time, the format of the Feast has been adapted.

During the evening, verses from Stephen Duck’s first and most famous poem, The Thresher’s Labour (1730), are read aloud. His poetry has some elements of ornate diction. As a promising youth, he had been given access to the classics of English literature by his charity-schoolteacher and other local worthies. However, the striking feature of Duck’s most famous work was its gritty realism. The Georgian agricultural year relied upon intensive and monotonous manual labour. And, at the height of the harvest, threshing the grain was tough work, continuing unabated throughout a long summer’s day. Stephen Duck recalled the experience:

In briny Streams, our Sweat descends apace,

Drops from our Locks, or trickles down our Face.

No Intermission in our Work we know;

The noisy Threshal [two-handed flail] must for ever go.

Neighbours who toasted the man and his muse were happy to admire, if not necessarily to share, this hard toil. During the eighteenth century, a quiet re-evaluation of the importance of manual work was taking place. John Locke and, especially, Adam Smith explored the contribution of labour to the creation of economic value. And readers in their parlours appreciated verses by poets from varied walks of life, including the newly literate workers.

Duck was thus a portent of change. Another poet from ‘low-life’ was Ann Yearsley (1753-1806), the Bristol ‘milk-woman’.3 She flourished a generation after Duck, with the support of a literary patron. Another example was the little-known James Woodhouse (1735-1820), ‘the shoemaker poet’, who eventually made a living as a bookseller.4 And in the early nineteenth century, John Clare (1793-1864), a farm labourer’s son from Northamptonshire, wrote poems of anguished beauty.5

All found it hard to progress from early success to something more permanent. The one exception was Scotland’s brilliant balladeer, Robert Burns (1759-96), the son of an Ayrshire tenant farmer.6 Financially, he always lived from hand to mouth, never attaining great riches. He did, however, have some ballast from his post as an exciseman [tax collector]. That enabled Burns to pour out his evocative poems and songs – thus mightily extending his audience. Today, he is honoured by the now world-wide tradition of annual Burns Night festivals,7 on a scale far, far exceeding the Duck Feast in Wiltshire.

By contrast, Stephen Duck lacked a steady profession. For a while, he enjoyed royal patronage and a pension from Queen Caroline, wife of George II. Yet, after her death in 1737, his career stalled. Duck later took orders as an Anglican clergyman. After all, there were major literary figures within the eighteenth-century Church of England – Jonathan Swift and Laurence Sterne being two outstanding exemplars.

Nonetheless, the clerical life did not suit Duck. Quite possibly he found that the social transition from the fields into literary and professional society, without a secure income, was too psychologically unsettling. Stephen Duck was also, in this great age of satire, the butt of robust teasing for his plebeian origins. And his best-known poem was quickly parodied, as The Thresher’s Miscellany (1730) – penned by an anonymous author who called himself Arthur Duck.8

It’s not easy, however, to read another’s heart. Stephen Duck’s life continued. He married twice; had children. It was some time before his career ran definitively into the sands. But, in 1756, he committed suicide.

Ultimately, Stephen Duck became and remained a quiet symbol of social advancement and literary change. He was not the only impoverished Georgian labourer’s son to gain fame. Captain James Cook (1728-79), the global explorer, came from a similar background. Yet, in his case, the navy provided a career structure (and a route to controversy via the mutual meetings/misunderstandings of global cultures).9 Cook’s name is now commemorated in many locations around the world. There is even a crater on the moon, named after him.

Stephen Duck, by contrast, is celebrated in Charlton in Wiltshire, not with a name-plate but, aptly enough, with a Feast. Just what was needed after a long day’s labour in the fields, as Duck had specified:

A Table plentifully spread we find,

And Jugs of humming Ale, to cheer the Mind …

ENDNOTES:

1 For context, see P.J. Corfield, The Georgians: The Deeds & Misdeeds of Eighteenth-Century Britain (2022); and website: https://www.thegeorgiansdeedsandmisdeeds.com.

2 R. Davis, Stephen Duck, the Thresher Poet (Orono, Maine, 1926).

3 A. Yearsley, Poems on Several Occasions (1785; reissued, 1994); R. Southey, Lives of Uneducated Poets (1836), pp. 125-34; K. Andrews, Ann Yearsley and Hannah More, Patronage and Poetry: The Story of a Literary Relationship (2015).

4 [J. Woodhouse], Poems on Sundry Occasions, by James Woodhouse a Journeyman Shoemaker (1764).

5 E. Blunden (ed.), Sketches in the Life of John Clare, Written by Himself (1974); J. Bate, John Clare’s New Life (Cheltenham, 2004); S. Kövesi, John Clare: Nature, Criticism and History (2017).

6 I. McIntyre, Robert Burns: A Life (1995; 2001); R. Crawford, The Bard: Robert Burns, a Biography (2011); G.S. Wilkie, Robert Burns: A Life in Letters (Glasgow, 2011).

7 PJC, BLOG/ 133 (Jan. 2022), in https://www.penelopejcorfield.com/monthly-blogs.

8 A. Duck [pseud.], The Thresher’s Miscellany (1730).

9 J. Robson (ed.), The Captain Cook Encyclopaedia (2004).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 136 please click here