MONTHLY BLOG 100, CONTROLLING STREET VIOLENCE & LEARNING FROM THE DEMISE OF DUELLING

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2019)

Young men carrying knives today can’t simply be equated with gentlemen duelling with rapiers in the eighteenth century. There are very many obvious differences. Nonetheless, the decline and disappearance of duelling has some relevant messages for later generations, when considering how to cope with an increase in violent street confrontations.

Both themes come under the broad rubric of controlling public expressions of male violence. By the way, such a proposition does not claim violence to be purely a masculine phenomenon. Still less does it imply that all men are prone to such behaviour. Yet it remains historically the case that weaponised acts of aggression in public and semi-public places tend to be undertaken by men – and, often, by young men at that.

Duelling developed in Europe from the sixteenth century onwards as a stylised form of combat between two aggrieved individuals.1 In terms of the technology of fighting, it was linked with the advent of the light flexible rapier, instead of the heavy old broadsword. And in terms of conflict management, the challenge to a duel took the immediate heat out of a dispute, by appointing a future date and time for the aggrieved parties to appear on the ‘field of honour’. At the appointed hour, the meeting did not turn into an instant brawl but was increasingly codified into ritual. ‘Seconds’ accompanied the combatants, to enforce the set of evolving rules and to see fair play. They were there as friendly witnesses but also, to an extent, as referees.2 In the eighteenth century, too, surgeons were often engaged to attend, so that medical attention was available if required.

Sometimes, to be sure, there were variants in the fighting format. On one occasion in 1688 two aristocratic combatants arrived, each supported by two seconds. At a given signal, all six men launched into an uninhibited sword-fight, in which all were wounded and two of the seconds died. However, such escalations were exceptional. The seconds often began the encounter by trying to reconcile the antagonists. If successful, the would-be duellists then shook hands and declared honour to be satisfied. Hence an unknown number of angry challenges never turned into outright fighting. Would-be violence in such cases had been deflected and socially contained.

Duels certainly remained a topic of both social threat and titillating gossip. They were dramatic moments, when individual destiny appeared heightened by the danger of imminent death. Later romantic novelists and film script-writers embraced the melodrama with unwearied enthusiasm. Yet the number of real-life duels in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Britain was tiny.

No accurate records are available, since such encounters were kept semi-clandestine. Nonetheless, contemporary legal records and newspaper reports provide some clues. Scrupulous research by the historian Robert Shoemaker has identified 236 duels in the metropolitan London area between 1660 and 1830.3 In other words, there were fewer than 1.5 duels per annum on average during these 170 years. The peak duelling decades were those of the later eighteenth century. Between 1776 and 1800, there were on average 4.5 duels per annum. Yet that total emerged from a ‘greater’ London with approximately one million inhabitants in 1801. Even taking Shoemaker’s figures as a minimum, they show that duelling was much rarer in practice than its legendary status implied.

In fact, the question might be put the other way round: why were there so many duels at all, when the practice was officially deplored? The answer has relevance to today’s discussions about knife carrying. Duelling was sustained by a degree of socio-cultural acceptance by men in elite society, who were prepared to risk the legal penalties for unlawful fighting, wounding or killing. Its continuance paid tribute to the power of custom, against the law.

By the early nineteenth century in Britain, when the practice was disappearing, it was pretty much confined to young elite men of military background. However, there were three high-profile cases when very senior Tory politicians rashly took to the field. In 1798 Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger exchanged shots with his Treasurer of the Navy. (Both missed; but Pitt retired to his bed for three weeks, overcome by stress). In 1809 George Canning, the Foreign Secretary, duelled with his fellow Cabinet member, Viscount Castlereagh, Minister for War. (Castlereagh was wounded but not fatally). Most dramatically of all, in 1829 the ‘Iron Duke’ of Wellington, then Prime Minister, confronted the Earl of Winchelsea, in a row over Catholic Emancipation. (Neither was hurt; and the Duke immediately travelled to Windsor to reassure the king that his government was not suddenly leaderless).

These ill-judged episodes were signs of the acute vehemence of political confrontations in highly pressurised times. However, critics were immediately scathing. They asked pertinently enough why the populace should obey the laws when such eminent figures were potentially breaching the peace? At very least, their rash behaviour did not encourage reverence for men in high office.

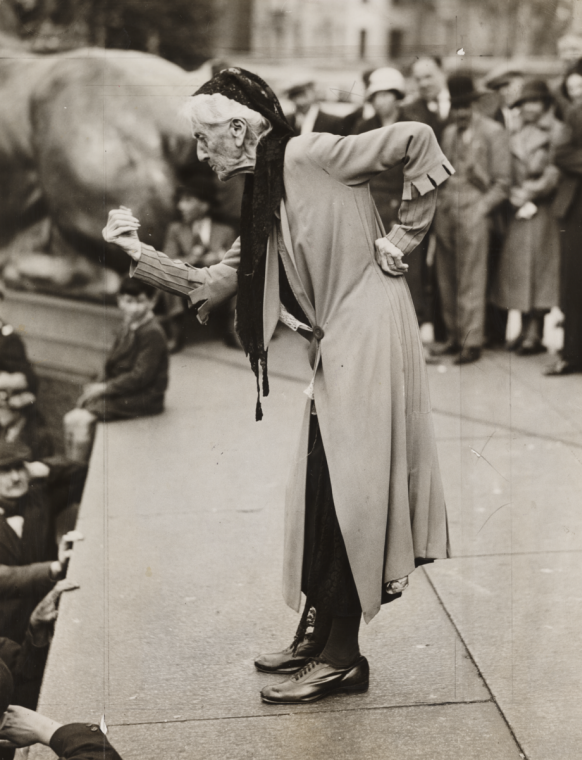

| Fig.2 Equestrian statue of Duke of Wellington, located in Royal Exchange Square, Glasgow: capping the statue with a traffic cone has become a source of local amusement, despite continued disapproval from Glasgow City Council and police. |

Public opinion was slowly shifting against duelling. There was no guarantee that the god of battle would give victory to the disputant who was truly in the right. Fighting empowered the bellicose over the irenic. Religious and civic authorities always opposed fighting as a means of conflict resolution. Lawyers were particularly hostile. Self-help administration of justice deprived them of the business of litigation and/or arbitration. Hence in 1822 a senior law lord defined duelling as ‘an absurd and shocking remedy for private insult’.

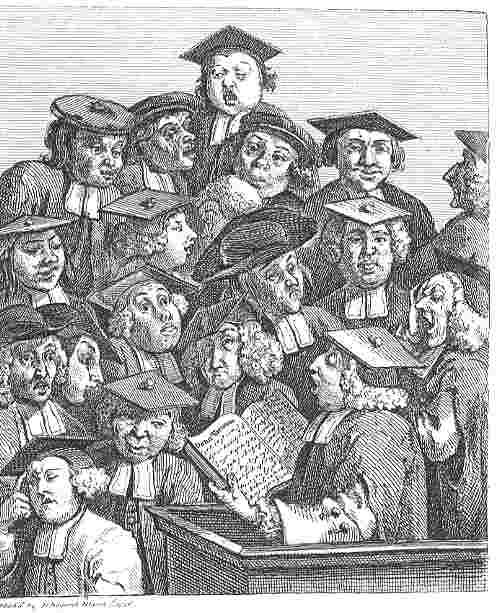

Other voices had long been arguing that case. In 1753 the novelist Samuel Richardson strove in Sir Charles Grandison to depict a good man who declined to fight a duel, despite being strongly provoked. True, many impatient readers found this saintly hero to be somewhat priggish. But Grandison stressed that killing or maiming a rival over a point of honour was actually the reverse of honourable.4 Bourgeois good sense was triumphing over aristocratic impetuosity, although the fictional Sir Charles had a title just to soothe any anxieties over his social respectability.

Another public declaration against duelling came from the down-to-earth American inventor and civic leader Benjamin Franklin (1706-90). In 1784 he rejected the practice as both barbaric and old-fashioned: ‘It is astonishing that the murderous practice of duelling … should continue so long in vogue’. His intervention was particularly notable, in that recourse to duelling was socially more widespread in the American colonies, with their ingrained gun culture.5 And Franklin stuck to his position, refusing to rise to sundry challenges

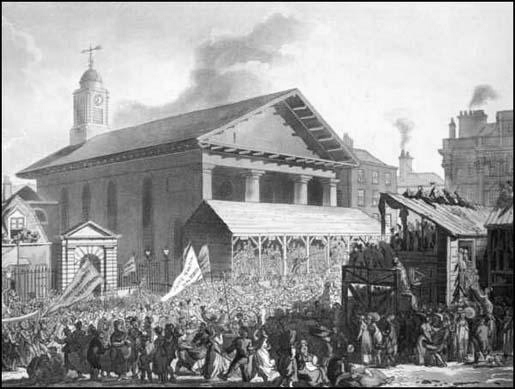

The force of such interventions in Britain helped to render public opinion decreasingly sympathetic to duellists. One pertinent example came from 1796. Early one morning, two Americans faced each other to duel in Hyde Park. But ten swimmers in the nearby Serpentine – some of them naked – jumped out of the water and ran to stop the fight. In this particular case, they were too late; and one contestant died. Nonetheless, witnesses testified in the ensuing murder trial that the crowd, many of middling social origins, had spontaneously intervened. Public attitudes were becoming hostile. And it was that shift, rather than major changes in law or policing, which caused the practice slowly to disappear. The last fatal duel in Scotland took place in 1826; the last in England/Wales (between two exiled Frenchmen) in 1852. When Prime Minister Peel was challenged to a political duel in the 1840s he immediately refused, on the grounds that such behaviour would be ‘childish’ as well as wrong.

Viewed in terms of Britain’s historical sociology, the decline of duelling was part of a complex process of everyday demilitarisation, in the context of the slow shift from a rural to an urbanised society. Gentlemen decreasingly carried swords for other than ceremonial purposes. Canes and umbrellas came into vogue instead. Sheridan’s play The Rivals (1775) poked fun at impetuous young gentlemen who are ready to fight for their honour. Yet they are aware that ‘a sword seen in the streets of Bath would raise as great an alarm as a mad dog’, as one character remarks. The combative Irish adventurer Sir Lucius O’Trigger is lampooned – a nice touch of auto-critique from Sheridan who came from Dublin and twice fought duels himself. And the country bumpkin Bob Acres, who is egged on to fight his rival, tellingly finds his valour ‘oozing away’ when it gets to the point.6 Audiences are invited to laugh, but sympathetically.

Interestingly, by 1775 Sheridan’s play was already behind the times in terms of the technology of fighting. By the 1760s duels had come increasingly to be fought with pistols. The last known sword duel in Britain occurred in 1785. This technological updating, supplied by industrious Birmingham gun-makers, had two paradoxical effects. On the one hand, it demonstrated that the art of duelling was quick to move with the times.

On the other hand, the advent of the pistol inadvertently saved lives. The statistics collected by Robert Shoemaker showed that unequivocally. Duels with swords, among his 236 recovered examples, resulted in deaths in 22 per cent of all cases; and woundings in another 25 per cent. By contrast, it was tricky to kill a man standing at a distance, especially with early pistols which lacked rifle sights for precise aiming. Among Shoemaker’s 236 cases, as few as 7 percent of duels with pistols resulted in death; while a further 22 percent led to woundings.

Or, the point can be put the other way round. A massive 71 percent of combatants were unharmed after an exchange of pistol shots, compared with 53 per cent of duellists who were unharmed after crossing swords. In neither case did a duel guarantee a bloodbath. But pistols were a safer bet, especially after conventions established that the combatants had to stand at a considerable distance from one another and had to wait for a signal, in the form of a dropping handkerchief, before taking aim and firing. No ‘jumping the gun’. Indeed one test case in 1750 saw a duellist on trial for murder because he had fired before his opponent was ready. So the victim had testified, plaintively, on his deathbed.

It was the unavoidable proximity of the combatants rather than their martial skills which led to the greater proportion of killings by swordsmen than by gunsmen. That fact is relevant to the experience of knife-carrying today. The number of fatalities is not a sign of a special outcrop of wickedness but rather the consequence of the chosen technology. Knife-wielding in anger at close quarters is intrinsically dangerous, whatever the level of fighting expertise.

Needless to say, the moral of this history is not that combatants should switch to guns. The much-enhanced technology of gunfire today, including the easy firing of multiple rounds, makes that option ever less socially palatable, if it ever was.

Instead, the clear requirement is to separate combatants and to ritualise the expression of social and personal aggression. Achieving such policies must rely considerably upon systems of law and policing. Yet socio-cultural attitudes among the wider public are highly relevant too. As the history of duelling indicates, even august Prime Ministers allowed themselves upon occasion to be provoked into behaving in ways that put them at risk of criminal charges. But changing social mores eventually removed that option, even for the most combative and headstrong of politicians today. Community attitudes at first ritualised the personal resolution of conflicts and eventually withdrew support for such behaviour entirely.

So today multiple approaches are required. Police actions to discourage young men from carrying knives constitute an obvious and important step. Ditto effective policies to curb the drug culture. Equally crucial are strong and repeated expressions of community disapproval of violence and knife-carrying. Yet policing and public attitudes can’t work without complementary interventions to combat youth alienation and, especially, to provide popular non-violent outlets for energy and aggression. Leaving bored young people feeling fearful and at risk in public places is no recipe for social order.

How can energies and aggression be either ritualised and/or channelled into other outlets? It’s for young people and community activists to specify. But many potential options spring to mind: youth clubs; youth theatre; participatory sports of all kinds; martial arts; adventure programmes; community and ecological projects; music-making festivals; dance; creative arts; church groups; … let alone continuing educational access via further education study grants. It’s true that all such plans involve constructive imagination, organisation, and expenditure. But their benefits are immense. Violence happens within societies; and so, very emphatically, does conflict resolution and, better still, the redirection of energies and aggression into constructive pathways.

1 See variously S. Banks, Duels and Duelling (Oxford, 2014); U. Frevert, Men of Honour: A Social and Cultural History of the Duel (Cambridge, 1995); V.G. Kiernan, The Duel in European History: Honour and the Reign of the Aristocracy (Oxford, 1988; 2016); M. Peltonen, The Duel in Early Modern England: Civility, Politeness and Honour (Cambridge, 2003); P. Spierenburg (ed.), Men and Violence: Gender, Honour and Rituals in Modern Europe and America (Columbus, Ohio, 1998).

2 S. Banks, ‘Dangerous Friends: The Second and the Later English Duel’, Journal of Eighteenth-Century Studies, 32 (2009), pp. 87-106.

3 R.G. Shoemaker, ‘The Taming of the Duel: Masculinity, Honour and Ritual Violence in London, 1660-1800’, Historical Journal, 45 (2002), pp. 525-45.

4 S. Richardson, The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753; in Oxford 1986 edn), Bk.1, pp. 207-8.

5 B. Franklin, ‘On Duelling’ (1784), in R.L. Ketcham (ed.), The Political Thought of Benjamin Franklin (Indianapolis, Ind., 1965; 2003), p. 362. For context, see also W.O. Stevens, Pistols at Ten Paces: The Story of the Code of Honour in America (Boston, 1940); D. Steward, Duels and the Roots of Violence in Missouri (2000); and C. Burchfield, Choose Your Weapon: The Duel in California, 1847-61 (Fresno, CA., 2016).

6 R.B. Sheridan, The Rivals (1775), ed E. Duthie (1979), Act V, sc. 2 + 3, pp. 105, 112. For the Irish context, see J. Kelly, ‘That Damn’d Thing Called Honour’: Duelling in Ireland, 1570-1860 (Cork, 1995).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 100 please click here