MONTHLY BLOG 135, A YEAR OF GEORGIAN CELEBRATIONS – 3: THE SCOTTISH MUSIC OF NIEL GOW

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2022)

|

Close-up of sculptor David Annand’s statue of legendary |

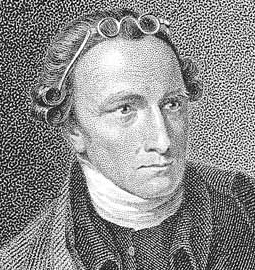

At a time of international crisis over Ukraine, it seems heartless to continue normal life. And, in particular, it could seem inappropriate to be writing about something as jolly and convivial as the music of eighteenth-century Scotland’s legendary fiddler, Niel Gow (1727-1807). But it helps to stick to routines, which in this case means posting my monthly BLOG.

Music, moreover, is a mighty medium for expressing the full range of human emotions. Niel Gow, born in Strathbaan, Perthshire, came from a modest background to become feted as a composer and fiddler.1 And, among his output, are some famous laments. Indeed, in the long eras before the advent of the radio, musicians had to be ready to switch quickly in style from sad to jolly, from slow to brisk, from simple to intricate, as occasion required. They provided their listeners with a soundtrack for both daily life and special events.

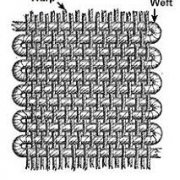

Gow initially began his working life as a weaver. Yet his manual dexterity and his musicality were, between them, sufficiently notable that he soon began to make a name as a fiddler. (A fiddle is the demotic name for a violin, when the instrument is used for ‘folk’ music). He then won some local competitions – which were taken seriously in Perthshire, a ‘big county’ that cherishes its musical traditions. And, once he found a well-connected patron, Gow was able to work as a professional musician.

James Murray, 2nd Duke of Atholl (1690-1764), was a successful Scottish politician, who lived down the Jacobite affiliations of his older brother (who lost his title and lands after 1715), and thereafter prospered as a solid pro-Unionist. He called upon the services of Gow to play music at balls and dances, held by the Scottish nobility. Such gatherings were, for Atholl, handy ways of shoring up pro-Hanoverian social networks.

For Gow, such employment was a break-through. It gave him access to a world of Scottish lairds who were ready to pay for his services at their social gatherings. The role of a professional musician was a new and potentially risky one. But he was able to flourish, and continued to do so, long after the Duke’s death in 1764. Gow meanwhile lived simply and brought up his large family in a traditional single-story stone cottage in Inver, near Dunkeld. Outside the village, on the banks of the Tay, is the massive oak tree, where he was reported to sit composing music.2 Yet Inver was also well placed for working trips into urban centres like Perth and Dundee. They gave him access to music publishers – and, via the press, to the wider world.

Scotland’s fast-expanding Lowland economy from the mid-eighteenth century onwards was becoming sufficiently wealthy to support not only the growth of towns, trade and industry but the parallel expansion of a new service economy.3 Musicians were among the emergent new professions. They provided a ‘whole Tribe of Singers and Scrapers’, fitted for ‘this Musical Age’, as one occupational handbook observed, somewhat wryly, in 1747.4 It was in that context, that Gow’s son Nathaniel was able to follow in his father’s footsteps. So he too played and composed for the fiddle.

Especially prominent among the output of Niel Gow were his Scottish country dances. Many are still played at ceilidhs and festive events today. Some were new compositions. Others were rearrangements or ‘borrowings’ (often unacknowledged) from older dance music.5 There was then, however, no stigma attached to such reworkings. Robert Burns similarly adapted older verses and tunes in his own prolific output, which also combined both old and new.6

Their audiences positively relished the consolidation of a proud ‘Scottish’ poetic and musical tradition.7 It brought old legacies into the mainstream. Any separatist tinge of association with the outlawed Jacobites – supporters of the exiled Stuart kings – was shed, whilst a living cultural heritage was enhanced.

So rich is this updated repertoire that English-speaking audiences to this day continue to enjoy Scottish dances and Highland laments. In part, global enthusiasm was boosted by the widespread Scottish diaspora. Yet music has always had the power to transcend ethnic and cultural boundaries.

To honour one notable creator of Scotland’s musical tradition, an annual Niel Gow Festival has been hosted each March since 2004, in the village of Dunkeld & Birnam (Perth & Kinross). The next will be held on 18-20 March 2022.8 This place is often described as a ‘Gateway to the Highlands’. Conversely, changing the motto, it might also be said that the music of Niel Ross constituted a cultural bridge from the Highlands to the wider world … Let that be a happy portent that out of old conflicts can come sustained peace and fertile creativity.

ENDNOTES:

1 For Niel Gow (1727-1807), see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niel_Gow [accessed 28 Feb. 2022]; and H. Jackson, Niel Gow’s Inver (Perth, 2000). Gow’s first name was sometimes rendered as Neil or Neal.

2 Now a tourist attraction: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niel_Gow’s_Oak [accessed 28 Feb. 2022].

3 D. Allen, Scotland in the Eighteenth Century; Union and Enlightenment (Harlow, 2002).

4 R. Campbell, The London Tradesman … (1757), p. 93. For context, see also C. Ehrlich, The Music Profession in Britain since the Eighteenth Century: A Social History (Oxford, 1985), pp. 1-53.

5 See tunes by Niel Gow, played on his own fiddle, in CD Album recorded by Pete Clark, Even Now: The Music of Niel Gow (Smiddymade Recordings SMD615, Perthshire, Scotland, 1999). And context in D. Johnson, Scottish Fiddle Music in the Eighteenth Century: A Music Collection and Historical Study (Edinburgh, 1984).

6 See e.g. C. Campbell and others, Burns and Scottish Fiddle Tradition (Edinburgh 2000); C.E. Andrews, The Genius of Scotland: The Cultural Production of Robert Burns, 1785-1834 (Leiden, 2015).

7 S. McKerrell and G. West (eds), Understanding Scotland Musically: Folk, Tradition and Policy (2018); F.M. Collinson, The Traditional and National Music of Scotland (2021).

8 For details, see https://www.niel-gow.co.uk.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 135 please click here