MONTHLY BLOG 124, BATTERSEA’S FEMALE PIONEERS

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2021)

In mid-February 2021, Battersea’s Labour MP Marsha de Cordova set a good challenge to me and to my friend and fellow historian of Battersea, Jeanne Rathbone.1 We were asked to nominate 31 pioneering women with a connection to the area. No problem. And then to write Twitter-length summaries of their achievements, especially in the local context, Trickier, as many of these women had richly multi-faceted lives. Plus, trickiest of all, to find authenticated photos of them all.

One case was extreme. The philanthropist Mrs Theodore Russell Monroe followed the reticent Victorian custom of using in public not only her husband’s surname but his given name as well. A quick search on Google for ‘Russell Monroe’ provided lots of information about the 1953 film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, starring Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe. But absolutely nothing about the laudable woman who in 1896 funded Battersea Hospital as a headquarters of the Anti-Vivisection movement.2 As a result, we cite Mrs Theodore Russell Monroe in the Victorian style to which she was accustomed. And, without dates or photo, she remains a monument of self-effacement.

Having (largely) met the good challenge, the 31 names and short citations were published, day by day throughout March 2021, on Marsha de Cordova’s web platform.3 It constituted her salutation, on behalf of Battersea, to National Women’s History Month.

Interestingly but not surprisingly, very few of these women were actually born within the area itself. But Battersea, like the surrounding greater London, has always attracted incomers to share its jostling mix of wealth and poverty. One who not only made that move but wrote eloquently about it was the author Nell Dunn. In 1959 she moved from ‘posh’ Chelsea to ‘plebeian’ north Battersea; and her prize-winning Up the Junction (1963; filmed 1968) won applause for its mix of gritty realism with warm cross-class sympathy.

As a further celebration of International Women’s Day on 8 March, Marsha de Cordova also hosted a well-attended (virtual) public meeting. It provided an excellent chance to take stock of what has changed – and to highlight what changes are still needed. It takes collective as well as individual action to improve the lot of women. And – needless to say – we cannot assume that all changes will automatically be progressive ones. History does reveal the existence of some world-wide and long-term trends (such as the spread of mass literacy). Yet, on the way, there are always fluctuations and sometimes outright backlashes and reversals. So women need continually to work together – and with men – to keep momentum for the right sort of changes.

By way of introducing the 8 March meeting, I organised presentations of five individual Battersea women’s lives.4 They were specifically chosen to show the range of fields open to female endeavour: politics and protest; aviation and technology; sports; literature; entertainment. Some of these areas were more traditional to women. Others, such as aviation and marathon-running, less so. The point for these women, all associated with Battersea, was either to open new doors – or to push further through doors that were already opened. It’s not career novelty per se which was required – but confidence and staying power.

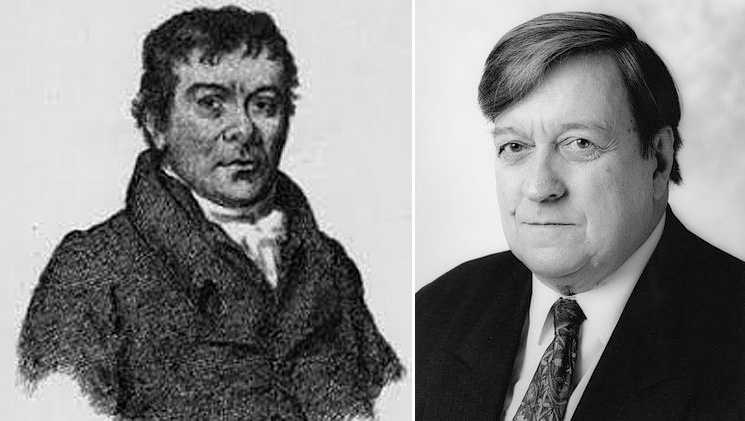

So who were the five exemplary women, emerging in successive generations? One was the long-lived and remarkable Charlotte Despard (1844-1939).5 She was a leading socialist reformer, suffragette campaigner, pacifist, supporter of Irish independence, and (in her later years) advocate of Russian communism. Never elected to parliament, she began her public career funding and personally running welfare projects in the industrial slums of Battersea’s Nine Elms. Gradually, she became a notable public figure, unworried as to whether she was in or out of political fashion. Among other things, she became a powerful stump orator, regularly addressing large outdoor meetings in an era when it was still rare for women to make public speeches.6 Above all, Despard developed her own philosophy of non-violent protest. And she influenced the young Mahatma Gandhi, who met Despard on his first visit to London in summer 1914 and was highly impressed. ‘She is a wonderful woman’, he wrote.

In the following generation, Hilda Hewlett (1864-1943) took women into the skies.7 She became fascinated by flight. She rejected the view, held by many men, that ‘the fair sex;’ did not have ‘the right kind of nerve’ for aviation. Hewlett was the first British woman to get a pilot’s license; the first to open (with a partner) a flying school; and the first to open (with the same partner) a factory to manufacture aircraft. (Many were used in the First World War). This venture was initially located in north Battersea, where there was a large skilled industrial workforce on hand. Hewlett was not only a force for change in her own right, but she opened doors for others too. Thus she trained not only young men but also young women in the skills of aviation and engineering. She was clear that new technology should empower all.

Overcoming obstacles by direct action was also the modus operandi of Violet Piercy (1889-1972).8 She proved to be a natural athlete. Yet she was constrained by traditional taboos about women in competitive sport. So Piercy began to run unofficial marathons, in a very public style. In 1926, she ran from Windsor Castle to Battersea Town Hall, close to her home. Eventually, in 1936 she was allowed to run an official marathon route but not as part of the male racing pack. Her ‘record’ stood for decades, until women were allowed freely into all competitive sports. Piercy’s aim was simple: ‘I did it to prove that a woman’s stamina can be just as remarkable as a man’s’. And through the efforts of pioneers like her, the barriers to women in sport were one by one overthrown.

Penelope Fitzgerald (1916-2000)9 wrote lovely, lyrical, downbeat novels. She had an often hand-to-mouth downbeat life, far from what she might have initially expected from her affluent, well-educated family background. And her novels’ themes were often downbeat too. Her experiences showed that adversity could strike anyone. Her family, in straitened circumstances, moved frequently, living in cheap lodgings in Battersea and for a while on a houseboat, moored in the Thames. (It sank, twice). Her most famous novel Offshore (1979) offered a wry literary evocation of the riverside community. Yet Fitzgerald found in writing a means of escaping – or transcending – her own woes; and her ultimate message was that people must hold on firmly to life, whatever happens.

Another exceptional woman was Elsa Lanchester (1902-86), who became a star of stage, TV and film.10 She rose from an unusual Bohemian left-wing childhood in south London, including Battersea, to have an international career. And she died in Hollywood. However, while she was praised for her humour and her versatility, she never had a break-through to film greatness. Instead, she was best known for her marriage to an undeniable star actor, Charles Laughton. They were a ‘celebrity couple’, in the public eye. But Lanchester firmly refused to answer any intimate enquiries. Their private life remained private. Laughton’s experiences as a gay or bisexual man were part of the coming world of gender/sexual flexibility. Amidst the glitz and speculation, Lanchester was staunch and dignified. She was a working woman and made her own way.

If these Battersea pioneers were to translate their experiences into mottoes for the early twenty-first century, what would they say? The following suggestions are improvised from their lives and recorded words.

Charlotte Despard would urge: ‘Fight – peacefully – against life’s injustices – and just don’t stop!’ [Note the adverb: ‘peacefully’]. Hilda Hewlett would add practical encouragement: ‘Plan well before you start your projects – but, after that, the sky’s the limit’. Violet Piercy would agree. ‘Women: just get out there and show the world what we can do’. And she too would add: ‘Don’t ever give up! Keep right on to the end of the road’. Meanwhile, Penelope Fitzgerald might well think: ‘It’s not always that easy’. But if pressed, she’d state firmly: ‘Even in adversity, find courage!’ And Elsa Lanchester would advise women to find both a public face and an inner self-confidence: ‘Chin up! … Smile for the cameras … And be proud to be yourself’. Confident individuals and groups then make confident movements.

ENDNOTES:

1 See J. Rathbone, Twenty Inspiring Battersea Women (in preparation 2021); with warm thanks to Jeanne for generously sharing her research.

2 There is scope for a good history of the Battersea General Hospital (closed 1972) and a skilled researcher should be able to find more details about the Hospital’s first funder.

3 In a late reshuffle of which I was unaware, a change was made to the list to insert ‘Penny Corfield, historian’. I remain shell-shocked. Most names on the list are historical figures, since time allows scope for proper critical distance. However, I thank Marsha de Cordova and her team for the huge compliment.

4 These were: Charlotte Despard, presented by Penelope Corfield; Hilda Hewlett, presented by Jeanne Rathbone; Violet Piercy, presented by Sonya Davis; Penelope Fitzgerald, presented by Carole Maddern; and Elsa Lanchester, presented by Su Elliott.

5 For Charlotte Despard, née French (1844-1939), see M. Mulvihill, Charlotte Despard: A Biography (1989); and PJC, ‘Why is the Remarkable Charlotte Despard Not Better Known?’, BLOG/97 (Jan. 2019); also available in PJC website https://www.penelopejcorfield.com/global-themes/gender-history/4.3.5.

6 PJC, Women and Public Speaking: And Why It Has Taken So Long to Get There. Monthly BLOG/47 (Nov. 2014); also in PJC website, as above 4.3.2.

7 For Hilda Hewlett, née Herbert (1864-1943), see G. Hewlett, The Old Bird: The Irrepressible Mrs Hewlett (Leicester, 2010).

8 For Violet Piercy (1889-1972), see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Violet_Piercy; and context in J. Hargreaves, Sporting Females: Critical Issues in the History and Sociology of Women’s Sports (1993).

9 For Penelope Fitzgerald, née Knox (1916-2000), see H. Lee, Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life (2013); and C.J. Knight, Penelope Fitzgerald and the Consolations of Fiction (2016).

10 Two indispensable sources are E. Lanchester, Charles Laughton and I (San Diego, 1938); and idem, Elsa Lanchester Herself (New York, 1984), while there remains scope for a thoughtful biography. See also C. Higham, Charles Laughton: An Intimate Biography (1976), with introduction by E. Lanchester.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 124 please click here