MONTHLY BLOG 40, HISTORICAL REPUTATIONS THROUGH TIME

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2014)

What does it take to get a long-surviving reputation? The answer, rather obviously, is somehow to get access to a means of endurance through time. To hitch a lift with history.

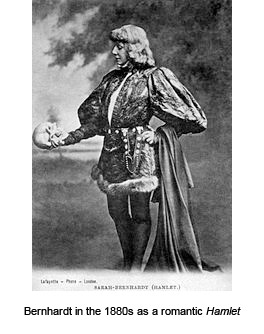

People in sports and the performing arts, before the advent of electronic storage/ replay media, have an intrinsic problem. Their prowess is known at the time but is notoriously difficult to recapture later. The French actor Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923), playing Hamlet on stage when she was well into her 70s and sporting an artificial limb after a leg amputation, remains an inspiration for all public performers, whatever their field.1 Yet performance glamour, even in legend, still fades fast.

What helps to keep a reputation well burnished is an organisation that outlasts an individual. A memorable preacher like John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, impressed many different audiences, as he spoke at open-air and private meetings across eighteenth-century Britain. Admirers said that his gaze seemed to pick out each person individually. Having heard Wesley in 1739, one John Nelson, who later became a fellow Methodist preacher, recorded that effect: ‘I thought his whole discourse was aimed at me’.2

What helps to keep a reputation well burnished is an organisation that outlasts an individual. A memorable preacher like John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, impressed many different audiences, as he spoke at open-air and private meetings across eighteenth-century Britain. Admirers said that his gaze seemed to pick out each person individually. Having heard Wesley in 1739, one John Nelson, who later became a fellow Methodist preacher, recorded that effect: ‘I thought his whole discourse was aimed at me’.2

Yet there were plenty of celebrated preachers in Georgian Britain. What made Wesley’s reputation survive was not only his assiduous self-chronicling, via his journals and letters, but also the new religious organisation that he founded. Of course, the Methodist church was dedicated to spreading his ideas and methods for saving Christian souls, not to the enshrining of the founder’s own reputation. It did, however, forward Wesley’s legacy into successive generations, albeit with various changes over time. Indeed, for true longevity, a religious movement (or a political cause, come to that) has to have permanent values that outlast its own era but equally a capacity for adaptation.

There are some interesting examples of small, often millenarian, cults which survive clandestinely for centuries. England’s Muggletonians, named after the London tailor Lodovicke Muggleton, were a case in point. Originating during the mid-seventeenth-century civil wars, the small Protestant sect never recruited publicly and never grew to any size. But the sect lasted in secrecy from 1652 to 1979 – a staggering trajectory. It seems that the clue was a shared excitement of cultish secrecy and a sense of special salvation, in the expectation of the imminent end of the world. Muggleton himself was unimportant. And finally the movement’s secret magic failed to remain transmissible.3

In fact, the longer that causes survive, the greater the scope for the imprint of very many different personalities, different social demands, different institutional roles, and diverse, often conflicting, interpretations of the core theology. Throughout these processes, the original founders tend quickly to become ideal-types of mythic status, rather than actual individuals. It is their beliefs and symbolism, rather than their personalities, that live.

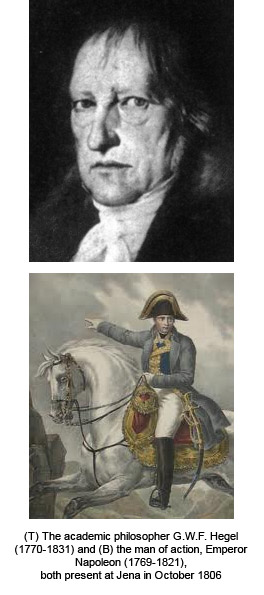

As well as beliefs and organisation, another reputation-preserver is the achievement of impressive deeds, whether for good or ill. Notorious and famous people alike often become national or communal myths, adapted by later generations to fit later circumstances. Picking through controversies about the roles of such outstanding figures is part of the work of historians, seeking to offer not anodyne but judicious verdicts on those ‘world-historical individuals’ (to use Hegel’s phrase) whose actions crystallise great historical moments or forces. They embody elements of history larger than themselves.

Hegel himself had witnessed one such giant personality, in the form of the Emperor Napoleon. It was just after the battle of Jena (1806), when the previously feared Prussian army had been routed by the French. The small figure of Napoleon rode past Hegel, who wrote: ‘It is indeed a wonderful sensation to see such an individual, who, concentrated here at a single point, astride a horse, reaches out over the world and masters it’.4

The means by which Napoleon’s posthumous reputation has survived are interesting in themselves. He did not found a long-lasting dynasty, so neither family piety nor institutionalised authority could help. He was, of course, deposed and exiled, dividing French opinion both then and later. Nonetheless, Napoleon left numerous enduring things, such as codes of law; systems of measurement; structures of government; and many physical monuments.5 One such was Paris’s Jena Bridge, built to celebrate the victorious battle.

The means by which Napoleon’s posthumous reputation has survived are interesting in themselves. He did not found a long-lasting dynasty, so neither family piety nor institutionalised authority could help. He was, of course, deposed and exiled, dividing French opinion both then and later. Nonetheless, Napoleon left numerous enduring things, such as codes of law; systems of measurement; structures of government; and many physical monuments.5 One such was Paris’s Jena Bridge, built to celebrate the victorious battle.

Monuments, if sufficiently durable, can certainly long outlast individuals. They effortlessly bear diachronic witness to fame. Yet, at the same time, monuments can crumble or be destroyed. Or, even if surviving, they can outlast the entire culture that built them. Today a visitor to Egypt may admire the pyramids, without knowing the names of the pharaohs they commemorated, let alone anything specific about them. Shelley caught that aspect of vanished grandeur well, in his poem to the ruined statue of Ozymandias: the quondam ‘king of kings’, lost and unknown in the desert sands.6

So lastly what about words? They can outlast individuals and even cultures, provided that they are kept in a transmissible format. Even lost languages can be later deciphered, although experts have not yet cracked the ancient codes from Harappa in the Punjab.7 Words, especially in printed or nowadays digital format, have immense potential for endurance. Not only are they open to reinterpretation over time; but, via their messages, later generations can commune mentally with earlier ones.

In Jena, the passing Napoleon (then aged 37) was unaware of the watching academic (then aged 36), who was formulating his ideas about revolutionary historical changes through conflict. Yet, through the endurance of his later publications, Hegel, who was unknown in 1806, has now become the second notable personage who was present at the scene. Indeed, via his influence upon Karl Marx, it could even be argued that the German philosopher has become the historically more important figure of those two individuals in Jena on 13 October 1806. On the other hand, Marx’s impact, having been immensely significant in the twentieth century, is also fast fading.

Who from the nineteenth century will be the most famous in another century’s time? Napoleon? Hegel? Marx? (Shelley’s Ozymandias?) Time not only ravages but provides the supreme test.

1 R. Gottlieb, Sarah: The Life of Sarah Bernhardt (New Haven, 2010).

2 R.P. Heitzenrater, ‘John Wesley’s Principles and Practice of Preaching’, Methodist History, 37 (1999), p. 106. See also R. Hattersley, A Brand from the Burning: The Life of John Wesley (London, 2002).

3 W. Lamont, Last Witnesses: The Muggletonian History, 1652-1979 (Aldershot, 2006); C. Hill, B. Reay and W. Lamont, The World of the Muggletonians (London, 1983); E.P. Thompson, Witness against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law (Cambridge, 1993).

4 G.W.F. Hegel to F.I. Neithammer, 13 Oct. 1806, in C. Butler (ed.), The Letters: Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1770-1831 (Bloomington, 1984); also transcribed in www.Marxists.org, 2005.

5 See http://napoleon-monuments.eu/Napoleon1er.

6 P.B. Shelley (1792-1822), Ozymandias (1818).

7 For debates over the language or communication system in the ancient Indus Valley culture, see: http://en.wikipedia.org/

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 40 please click here

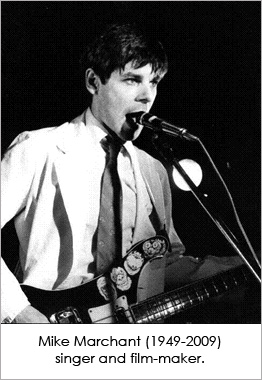

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide.

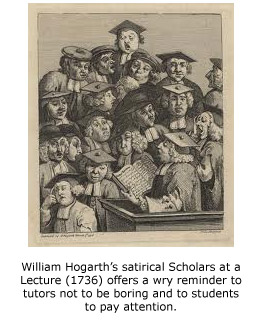

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide. On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’.

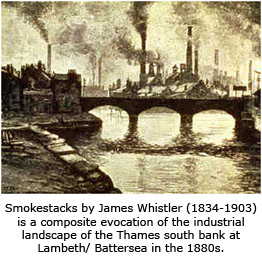

On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’. But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort.

But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort. The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends).

The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends). Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =

Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =