MONTHLY BLOG 20, IN PRAISE OF DISTINCTIVE CITIES – AND AGAINST THE MARCH OF HIGH-RISE ANYWHERE-CITY

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2012)

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital.

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital.

This BLOG has general bearings but it is specifically prompted by the publication of my new, expanded booklet on Vauxhall, Sex and Entertainment.1 The history of London’s pioneering pleasure gardens, which triumphantly eroticised the eighteenth-century leisure industry, may seem far distant from today’s plans to redevelop the Vauxhall area into a ‘mini-Manhattan’. (See my April 2012 BLOG). There is, however, an urgent link. We need to reject the march of high-rise anywhere-city – and to keep or restore urban distinctiveness.

Variety is the spice. Trite, but fundamentally right. And authenticity is absolutely essential too.

Many congratulations are rightly paid to the planners/ architects/ politicians/ people for preserving central Paris from the march of identikit high-rise development. That success includes some luck in avoiding wartime devastation but has relied on good judgment thereafter. And, around the globe, the same applies to all those historic towns which have kept their traditional topography and ambience. Udaipur in Rajasthan is but one spectacular example.

Yet, even after praising distinctive cities, it’s worth recalling that many places with sparky urban centres also contain inner-urban and suburban areas that are dire. Areas lose human scale when urban thoroughfares and junctions become too massive; when factory zones are kept isolated, featureless, and dilapidated – especially if their core industries are declining; when shopping malls slowly kill in-town high streets and local shops; and when mass housing estates are left without shops, cafes, pubs, post offices, jobs, viable parks and social amenities. Above all, it’s a disaster if the building of new homes, with modern facilities, simultaneously fail to build functioning communities.

In response, the crucial thing is to get planners, architects, developers, politicians and people to think in terms of the entire lived environment – including the local and regional context, and the prevailing landscape and weather conditions.

Why is all the literature about tall buildings concerned with the effects of heat/wind/weather on the said buildings? But virtually nothing is available on the overshadowing and wind channelling effects of such high-risers upon people and the wider environment.

Too much of the serious planning/development focuses upon just one plot of land; or upon just one building, whether supposedly ‘iconic’ or otherwise. Yet the test should not be for an architect to dream up a strange shape, which is then set as a challenge for an engineer to realise it. Buildings should be part of a townscape, not imposed upon it.

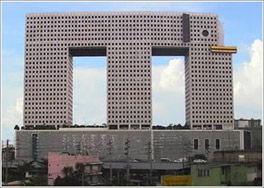

Of course, views of architectural monuments are subjective. Google-search the ‘world’s ugliest building’ and the Elephant Tower, Bangkok, is often nominated, shown here in this 2009 photograph.2 It is not necessarily the jokey concept that is criticised but especially its bleak implementation.

But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality.

But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality.

Plenty of high-rise buildings, which were praised when first installed, have now been removed as urban and social disasters. It’s not the scale per se which makes some constructions succeed and some fail. It’s the full context and the full experience. We need a good global debate and update upon Jane Jacobs’s humanist tract on the Death and Life of Great American Cities.3

It’s also right to rectify mistakes where buildings have been removed without due thought. Congratulations therefore to historic Datong in China’s Shanxi prefecture, to the west of Beijing. Known as today’s gritty ‘city of coal’, it features among lists of the world’s most polluted cities. Yet, as a sign of good intentions to improve, Datong is rebuilding its great Ming dynasty city walls, which were destroyed in the 1980s in the name of ‘modernity’.4 Let’s have more, more.

Erasing buildings entails erasing past thoughts as well as past deeds. Pulling down the old may well have to be done. But we need to be confident that our new thoughts and deeds are better, and that we fit new constructions into a whole environment of living and liveable cities.

My current example refers to plans to redevelop London’s Vauxhall into a ‘mini-Manhattan’. Why should a low marshy area of Thames bankside, far from the river mouth, emulate the high-rise effect of New York at its distinctive location at the confluence of the Hudson and the Atlantic? If London needs such an attempt, then Canary Wharf is already trying.

Vauxhall could certainly do with improvement. But, unlike some parts of London, it has an exotic past. From the later seventeenth century to 1859, it was the home of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens.5 This venue popularised the urban leisure park. It provided an attractive combination of music, dancing, food, drink, variegated entertainments, and an eroticised ambience of sexual dalliance. Not surprisingly, it packed in the crowds, both high and low.

What could the memory of the old Pleasure Gardens contribute to London’s Vauxhall area today?

For a start:

• Lots of trees and rose-bushes, lining streets, riverside, parks, and open spaces. Vauxhall was a prime place for courting couples to visit. The nightingales that once serenaded the lovers won’t come back. But why not the indigenous trees? They can help to absorb the noxious exhaust fumes at this polluted traffic interchange; and their flourishing (or otherwise) will signal whether London’s air is getting any cleaner.

• How about arches over the street-scene to generate attractive vistas? And some colonnades; and some statuary? In the eighteenth-century Gardens, there were monuments to John Milton and Georg Handel. But today they could honour Jonathan Tyers, who organised the Gardens in the 1730s, and William Hogarth, who probably designed their dramatic scenery – as seen in the following eighteenth-century print.

• A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

• A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

• More financial and community support for the current imaginative updating of the public open space, now renamed the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, on the site of the old Gardens?6

• And, lastly, some commemoration of Vauxhall as a place for lovers? I don’t know how that’s to be done; and it’s true that love usually evades the planning process. But maybe a statue to Mary Perdita Robinson, a celebrated/notorious eighteenth-century actor and lover, who appeared prominently in Rowlandson’s iconic painting of Vauxhall Gardens in 1784? At very least, it would offer a reminder that women as well as men helped to make old Vauxhall famous as an urban rendez-vous.

1 P.J. Corfield, Vauxhall, Sex and Entertainment: London’s Pioneering Urban Pleasure Garden (History & Social Action Publication: London, 2012) – available after 26 May 2012 via ; or www.historysocialaction.co.uk.

2 One commentator remarks that ‘the building is 10,000 times bigger than a real elephant, and 10,000 times uglier too’: CNN www.cnngo.com/explorations, 11 Feb. 2011.

3 Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Random House: New York, 1961; and many later edns).

4 For Datong, see ‘Chinese City’s Bid to Revive Glory of Imperial Past’, BBC News, 3 May 2010; and for context, I. Mohan, The World of Walled Cities: Conservation, Environmental Pollution, Urban Renewal and Developmental Prospects (Mittal: New Delhi, 1992).

5 See Corfield, Vauxhall, Sex and Entertainment; D. Coke and A. Borg, Vauxhall Gardens: A History (Yale University Press: London, 2011); and website: www.vauxhallgardens.com

6 For details, see: www.friendsofvauxhallpleasuregardens.org.uk

7 Consult Paula Byrne, Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson (Harpercollins: London, 2004); and May Robinson, The Memoirs of Mary Robinson ‘Perdita’, Edited by her Daughter (London, 1894).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 20 please click here

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone.

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone. And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed.

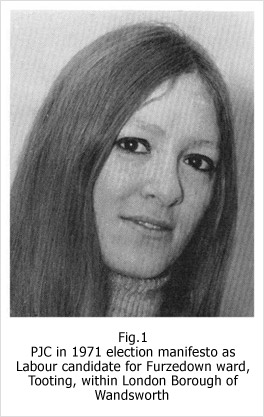

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed. So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece.

So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece.

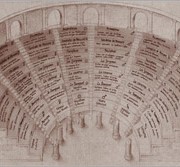

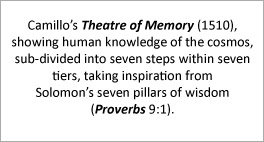

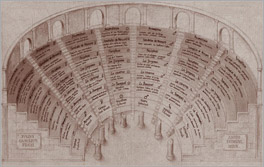

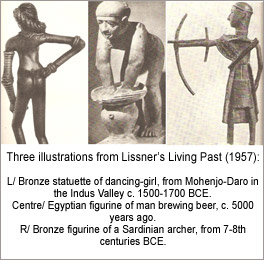

I remember reading this work with fascination as a teenager in the 1960s and then letting it lie fallow, as it was so far removed from anything in the normal History curriculum, either at school or university.

I remember reading this work with fascination as a teenager in the 1960s and then letting it lie fallow, as it was so far removed from anything in the normal History curriculum, either at school or university. Above all, the text conveyed the implicit assumption that, with historical effort and study, one human could understand, even if not approve, the culture of any other, anywhere around the world – and at any time.

Above all, the text conveyed the implicit assumption that, with historical effort and study, one human could understand, even if not approve, the culture of any other, anywhere around the world – and at any time.

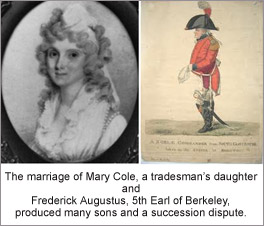

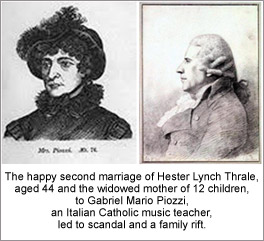

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator.

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator. So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury.

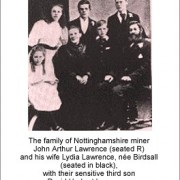

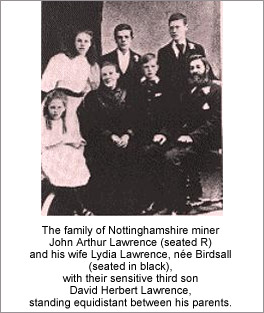

So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury. In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4

In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4

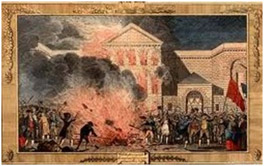

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.