MONTHLY BLOG 60, WRITING THROUGH A BIG RESEARCH PROJECT, NOT WRITING UP

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2015)

My heart sinks when I hear someone declare gaily: ‘I’ve done all the research; now all I have to do is write it up’.1 So what’s so wrong with that? It sounds so straightforward. First research, then sit down and write. Then, bingo, big party with lots of happy friends and relieved research supervisor.

But undertaking a big project in the Humanities or Social Sciences doesn’t and shouldn’t work like that.2 So my heart sinks on behalf of any researcher who declares ‘All I have to do is write it up’, because he or she has been wasting a lot of time, under the impression that they have been working hard. Far from being close to the end of a big project, they have hardly begun.

Why so? There are both practical and intellectual reasons for ‘writing through’ a big research project, rather than ‘writing up’ at the end. For a start, stringing words and paragraphs together to construct a book-length study takes a lot of time. The exercise entails ordering a miscellany of thoughts into a satisfactory sequence, marshalling a huge amount of documented detail to expound the sustained argument, and then punching home a set of original conclusions. It’s an arduous art, not an automatic procedure.

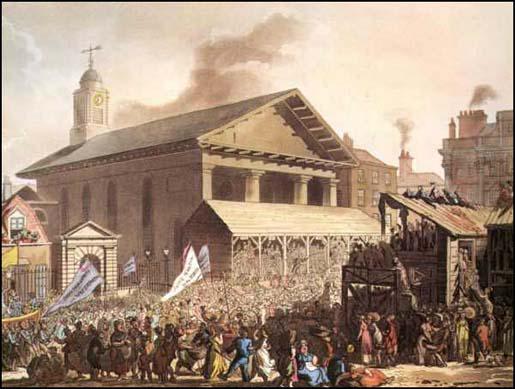

|

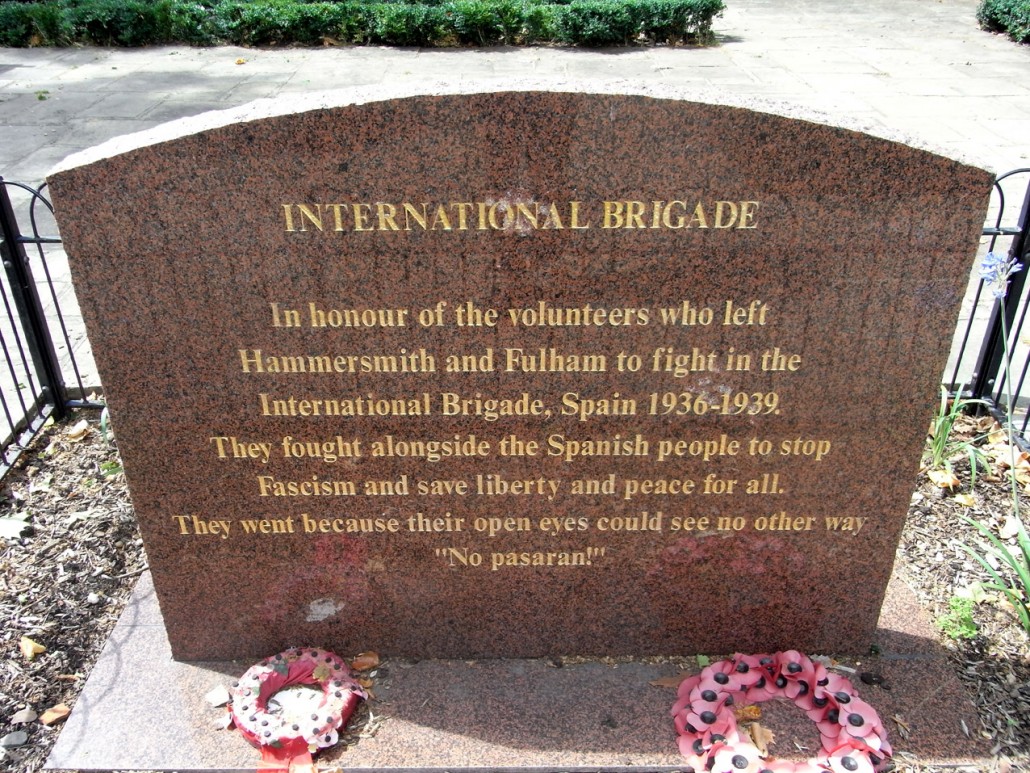

Hogarth’s Distrest Poet (1741) expresses the agonies of composition, as he sits in a poky garret, poor and dishevelled, with abandoned drafts at his feet. |

Writing and research in the Humanities and Social Sciences should thus proceed in tandem. These tasks between them provide the necessary legs which enable a project to advance. No supervised researcher should be without a target deadline for a forthcoming report or interim paper, which collectively function as prototype chapters. That rule applies from the onset, starting with a written review of the research questions, or bibliographical overview, or primary source search – or however the project is launched. Without ‘writing through’, researchers do not really appreciate what they have found or what they are arguing. Certainly there will be much redrafting and revision, as the research progresses. That’s all part of the process.

But grappling with ideas to turn them into a sustained account in written words is not just a medium for communication. It’s a mechanism for cogitation itself. Just as spoken language crystallises instinctive feelings into expressed thoughts, so the process of turning thoughts into written form advances, clarifies and extends their meaning to form a considered analysis. A book can say much more than a speech, because it’s longer and more complexly structured than even the longest speech. Writing through continually means thinking through properly.

Incidentally, what about prose style? The answer is: suit yourself. Match your personality. Obviously, suit the subject-matter too. Snappy dictums are good value. I enjoy them myself. They punch an argument home. But non-stop bullet-points are wearing. Ideas are unduly compressed. Readers can be stunned. The big argument goes missing. Writing short sentences is fun. Brevity challenges the mind. I could go on. And on. One gets a second wind. But content is also required. Otherwise, vacuity is revealed. And exhaustion threatens. So arguments need building. One point after another. There may be an exception. Sometimes they prove the rule. Sometimes, however, not. It depends upon the evidence. Everything needs evaluation. Points are sometimes obvious. Yet there’s room for subtlety. Don’t succumb to the obvious. Meanings multiply. Take your time. Think things through. Test arguments against data. There’s always a rival case. But what’s the final conclusion? Surely, it’s clear enough. Think kindly of your readers. Employ authorial diversity. Meaning what exactly? [162 words in 39 sentences, none longer than five words]

Alternatively, the full and unmitigated case for long, intricate, sinuous, thoughtful yet controlled sentences, winding their way gracefully and inexorably across vast tracts of crisp, white paper can be made not only in terms of academic pretentiousness – always the last resort of the petty-minded – but also in terms of intellectual expansiveness and mental ‘stretch’, with a capacity to reflect and inflect even the most subtle nuances of thought, although it should certainly be remembered that, without some authorial control or indeed domination in the form of a final full-stop, the impatient reader – eager to follow the by-ways yet equally anxious to seize the cardinal point – can find a numbing, not to say crushing, sense of boredom beginning to overtake the responsive mind, as it struggles to remember the opening gambit, let alone the many intermediate staging posts, as the overall argument staggers and reels towards what I can only describe, with some difficulty, as the ultimate conclusion or final verdict: The End! [162 words in one sentence, also fun to write].3

In other words, my stylistic advice is to vary the mix of sentence lengths. A combination of an Ernest-Hemingway-style brevity4 with an Edward Gibbonian luxuriance allows points to be fully developed, but also summarised pithily.

Thus, in order to develop a sustained case within a major research project, my organisational advice is to ‘write through’ throughout. That’s the only real way to germinate, sustain, develop, understand innerly and simultaneously communicate a big overarching picture, complete with supporting arguments and data. Oh, and my final point? Let’s banish the dreadful phrase ‘writing up’. It means bodging.

| A snappy dictum from the American journalist and writer William Zinsser (1922-2015). |

1 This BLOG is a companion-piece to PJC BLOG/59, ‘Supervising a Big Research Project to Finish Well and on Time: Three Framework Rules’ (Nov. 2015). Also relevant is PJC BLOG/34 ‘Coping with Writer’s Block’ (Oct. 2013).

2 In the Sciences, the model is somewhat different, according to the differential weight given to experimental research processes/outcomes and to written output.

3 My puny effort barely registers in the smallest foothills of lengthy sentences in the English language, one celebrated example being Molly Bloom’s soliloquy as finale to James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), reportedly in a sentence of over 4,000 words.

4 Hemingway is commonly cited as the maestro of pithiness. Yet the playwright Samuel Beckett also shares the honours in the brevity stakes, writing in sharp contradistinction to his friend and fellow-Irishman James Joyce.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 60 please click here