MONTHLY BLOG 13, CROSS-CLASS MARRIAGE IN HISTORY

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2011)

People often imagine that class barriers were more rigid in the past, notwithstanding historical fluctuations in social attitudes. As a result, it is always assumed that cross-class marriages were especially rare. Yet matters were never so simple. Among the many individuals in the past, who had sexual relationships across class boundaries (a comparatively frequent occurrence), there were always some who were bold enough to marry across them.

One case, among several aristocratic examples from the eighteenth century, was the marriage of the 5th Earl of Berkeley to Mary Cole, the daughter of a Gloucester butcher. She made a dignified wife, living down the social sneers. The Berkeleys began to live together in 1785 and did not marry publicly until 1796, although the Earl claimed that there had been an earlier ceremony.

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator.

This confusion led to a succession dispute. Eventually, the sons born before the public wedding were disbarred from inheriting the title, which went to their legitimate younger brother. Here the difficulty was not the mother’s comparatively ‘lowly’ status but the status of the parental marriage. It affected the succession to a noble title, which entitled its holder to attend the House of Lords. But the disbarred older siblings did not become social outcasts. Two of the technically illegitimate sons, born before the public marriage, went on to become MPs in the House of Commons, while the legitimate 6th Earl modestly declined to take his seat as a legislator.

Another example, this time from the nineteenth century, was that of Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh. He was the wealthy owner of Uppark House (Sussex), who in 1825 married for the first time, aged 70. His bride was the 21-year-old Mary Ann Bullock, his dairymaid’s assistant. She inherited his estate, surviving him for many years. Everything at Uppark was kept as it was in Sir Harry’s day. The estate then went to her unmarried sister who, as ‘her leddyship’ in her very old age, appeared to epitomise the old landed society – so much did outcomes triumph over origins. The young H.G. Wells, whose mother was housekeeper at Uppark, mused accordingly:1

In that English countryside of my boyhood every human being had a ‘place’. It belonged to you from your birth like the colour of your eyes, it was inextricably your destiny. Above you were your betters, below you were your inferiors…

The social conventions, within such a hierarchy, did allow for some mobility. High-ranking men raised their wives to a matching status, giving aristocratic men some room for manoeuvre. Against that, noble families generally did their best to ensure that heirs to grand titles did not run away with someone entirely ‘unsuitable’.

A tabulation of the first-marriage choices of 826 English peers, made between 1600 and 1800, showed that, in sober reality, most (73 percent) chose a bride from an equally or nearly equally titled background.2 The homogeneity of the elite was generally preserved.

Interestingly, however, just over one quarter (27 percent) of these English peers – a far from negligible proportion – were more socially venturesome. Their wives from ‘lower’ social backgrounds tended to be daughters of professional men or of merchants. In particular, a splendid commercial fortune was an ideal contribution in terms of bridal dowry; and, in such circumstances, aristocratic families found themselves willing to accept theoretically humbler connections with businessmen ‘in trade’.

Marriages like that of Sir Harry were ‘outliers’ in terms of the social distance between bride and groom. But his matrimonial decision to leap over conventions of social distance was not unique.

For women of high rank, meanwhile, things were more complicated. By marrying ‘down’, they lost social status; and their off-spring, however well connected on the mother’s side, took their ‘lower’ social rank from the father.

Nonetheless, it was far from unknown for high-born women to flout convention. In particular, wealthy widows might follow their own choice in a second marriage, having followed convention in the first. One notable example was Hester Lynch Salusbury, from a Welsh landowning family. She married, firstly, Henry Thrale, a wealthy brewer, with whom she had 12 children, and then in 1784 – three years after Thrale’s death – Gabriele Piozzi, an Italian music teacher and a Catholic to boot.3

Scandal ensued. Her children were affronted. And Dr Johnson, a frequent house-guest at the Thrale’s Streatham mansion, was decidedly not amused. Undaunted, Hester Lynch Piozzi and her husband retired to her estates in north Wales, where they lived in a specially built Palladian villa, Brynbella.

So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury.

So little was damage done to the family’s long-term status that her (estranged) oldest daughter married a Viscount. Furthermore, the Piozzis’ adopted son, an Italian nephew of Gabriele Piozzi, inherited the Salusbury estates, taking the compound name Sir John Salusbury Piozzi Salusbury.

If, after the initial fuss, the partners in a cross-class union lived respectably enough, the wider society tended sooner or later to condone the ‘mésalliance’. Feelings were soothed by respect for marriage as an institution. And the wider social stability was ultimately served by absorbing such dynastic shocks rather than by highlighting them.

Little wonder that many a novel dilated on the excitements and tensions of matrimonial choice. Not only was there the challenge of finding a satisfactory partner among social peer-groups but there was always some lurking potential for an unconventional match instead of a conventional union.

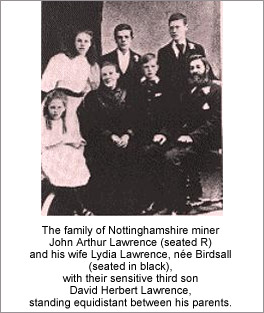

Such possibilities – complete with hazards – applied at all levels of society. In the early twentieth century, the family of D.H. Lawrence epitomised a different set of cross-class tensions. His father was a scarcely literate miner from Eastwood, near Nottingham, while his mother was a former assistant teacher with strong literary interests, who disdained the local dialect, and prided herself on her ‘good old burgher family’. From the start, they were ill-assorted.

In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4

In his youth, D.H. Lawrence was his mother’s partisan and despised his father as feckless and ‘common’. Later, however, he switched his theoretical allegiance. Lawrence felt that his mother’s puritan gentility had warped him. Instead, he yearned for his father’s male sensuousness and frank hedonism, though the father and son never became close.4

Out of such tensions came Lawrence’s preoccupation with man/woman conflict and with unorthodox sex and love. His parent’s strife was also more than mirrored in his own turbulent relationship with Frieda von Richtofen, the daughter of a Silesian aristocrat, who was, when they met, married to a respected Nottingham University professor.

Initial social distance between a married couple could lend enchantment – or the reverse. Cross-class relationships have been frequent enough for there to have been many cases, both successful and the reverse. Later generations always underestimate their number. But we should not ignore the potential for cultural punch (positive or negative) when couples from different backgrounds marry, even in times when class barriers are less than rigid. Nor should we underestimate society’s long-term ability to absorb such shocks, which would have to happen in great numbers before a classless society might be achieved.

1 H.G. Wells, Tono-Bungay (1909; in 1994 edn), pp. 10-11. For more about the Fe(a)therstonhaugh marriage and the context of Sussex landowning society, see A. Warner, ‘Finding the Aristocracy, 1780-1880: A Case Study of Rural Sussex’ (unpub. typescript, 2011; copyright A. Warner, who can be contacted via PJC).

2 Figures calculated from data in J. Cannon, Aristocratic Century: The Peerage of Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge, 1984), p. 85: Table 20. Note that the social status of each bride is derived from the rank of her father, so possibly obscuring a more variegated background in terms of her maternal inheritance.

3 Details of their courtship and Hester Thrale’s meditations on their disparities in rank are available on the website: www.thrale.com.

4 R. Aldington, Portrait of a Genius but …: The Life of D.H. Lawrence (1950), pp. 3-5, 8-9, 13, 15, 334.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 13 please click here

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.

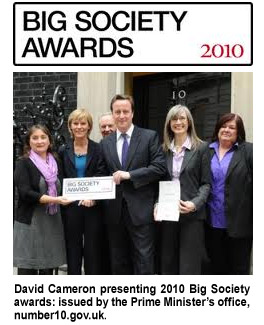

For that reason, David Cameron’s slogan enrages many people, not only on the centre and left in politics, but also on the Thatcherite right, who prefer individualist rather than communal alternatives to the state. In addition, plenty of non-political grass-roots activists dislike the term too. It appears as though a currently powerful section of one political party is trying to ‘own’ the countless manifestations of community life.2

For that reason, David Cameron’s slogan enrages many people, not only on the centre and left in politics, but also on the Thatcherite right, who prefer individualist rather than communal alternatives to the state. In addition, plenty of non-political grass-roots activists dislike the term too. It appears as though a currently powerful section of one political party is trying to ‘own’ the countless manifestations of community life.2 But organic expressions of civil society began long before David Cameron invoked the ‘Big Society’ to purge the Tory’s anti-society image and will continue long after the current government has disappeared.3

But organic expressions of civil society began long before David Cameron invoked the ‘Big Society’ to purge the Tory’s anti-society image and will continue long after the current government has disappeared.3 Secondly: the pre-committed research framework. Programmes should not start by ruling out all the research options. In this case, it cannot be taken for granted that ‘the’ central state is ‘the’ problem for those seeking to build communities. Governments in contemporary societies are very variegated and diverse in their roles and structures. Their impact can in some circumstances be inimical or discouraging to community activism.

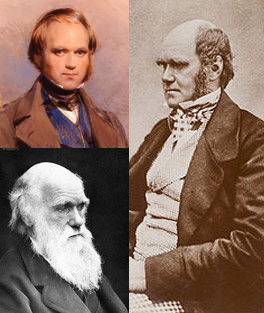

Secondly: the pre-committed research framework. Programmes should not start by ruling out all the research options. In this case, it cannot be taken for granted that ‘the’ central state is ‘the’ problem for those seeking to build communities. Governments in contemporary societies are very variegated and diverse in their roles and structures. Their impact can in some circumstances be inimical or discouraging to community activism. But it didn’t work. Long before Lysenko’s teachings were officially discredited as fraudulent in 1964, they were sidelined in practice. In wartime, Stalin learned the hard way that he had to trust his generals to fight the war. Yet he did not get the message in science, or indeed in other subjects, like history, where he intervened to support one argument as Marxist orthodoxy against another as ‘bourgeois’ revisionism. Between them, Stalin and Lysenko halted Russian biological studies and palpably harmed Soviet agriculture for over a generation, greatly weakening Soviet Russia as an international power.4

But it didn’t work. Long before Lysenko’s teachings were officially discredited as fraudulent in 1964, they were sidelined in practice. In wartime, Stalin learned the hard way that he had to trust his generals to fight the war. Yet he did not get the message in science, or indeed in other subjects, like history, where he intervened to support one argument as Marxist orthodoxy against another as ‘bourgeois’ revisionism. Between them, Stalin and Lysenko halted Russian biological studies and palpably harmed Soviet agriculture for over a generation, greatly weakening Soviet Russia as an international power.4 As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration.

As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration. Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

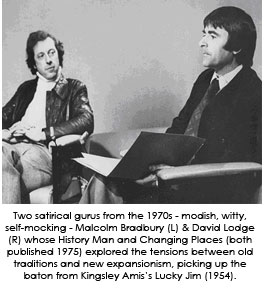

In fact, the reality is different in many ways. The tertiary sector is very variegated. It has faults, but they are often too neo-brutally managerialist rather than slumberingly Porterhousian.

In fact, the reality is different in many ways. The tertiary sector is very variegated. It has faults, but they are often too neo-brutally managerialist rather than slumberingly Porterhousian.

Divisions between Universities are now institutionalised into rival lobby organisations. The Russell Group (founded 1994) represents 20 Universities, self-defined as the research elite, constituting a limited company (no: 6086902), operating from a base in Cambridge. Feeling excluded, another 19 smaller research institutions created the 1994 Group to defend their research credentials. It operates with an Executive Board, chaired by an academic, with at least five permanent staff members. A similar corporate structure services the University Alliance, which represents 23 ‘major business-focused’ Universities. And from 1997 onwards the Campaign for Mainstream Universities (CMU) has organised 27 former Polytechnics and University colleges – then known as ‘new’ Universities although many already had long histories. This group now operates as a London-based Think-tank, known as the Million+ Group. These divisions mark a classic case of self-divide and be ruled.

Divisions between Universities are now institutionalised into rival lobby organisations. The Russell Group (founded 1994) represents 20 Universities, self-defined as the research elite, constituting a limited company (no: 6086902), operating from a base in Cambridge. Feeling excluded, another 19 smaller research institutions created the 1994 Group to defend their research credentials. It operates with an Executive Board, chaired by an academic, with at least five permanent staff members. A similar corporate structure services the University Alliance, which represents 23 ‘major business-focused’ Universities. And from 1997 onwards the Campaign for Mainstream Universities (CMU) has organised 27 former Polytechnics and University colleges – then known as ‘new’ Universities although many already had long histories. This group now operates as a London-based Think-tank, known as the Million+ Group. These divisions mark a classic case of self-divide and be ruled.

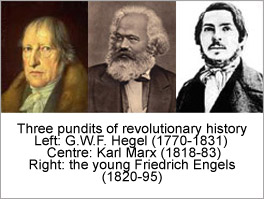

Secondly: political revolutions also need to be located within a spectrum of different sorts and degrees of change. It is very rarely, if ever, that everything is transformed all at once. The rhetoric of dramatic metamorphosis is both fearful and hopeful: ‘All changed, changed utterly;/ A terrible beauty is born’, as Yeats saluted the Irish Easter Rising in 1916. Yet, when the dust dies down, continuity turns out to have dragged at the heels of revolution after all. What is known as admirable heritage to its fans is deplorable inertia to its critics. Thus Karl Marx once denounced with righteous passion: ‘the tradition of all the dead generations [that] weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’.

Secondly: political revolutions also need to be located within a spectrum of different sorts and degrees of change. It is very rarely, if ever, that everything is transformed all at once. The rhetoric of dramatic metamorphosis is both fearful and hopeful: ‘All changed, changed utterly;/ A terrible beauty is born’, as Yeats saluted the Irish Easter Rising in 1916. Yet, when the dust dies down, continuity turns out to have dragged at the heels of revolution after all. What is known as admirable heritage to its fans is deplorable inertia to its critics. Thus Karl Marx once denounced with righteous passion: ‘the tradition of all the dead generations [that] weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living’. Yet no. Not only does fundamental change frequently develop via evolutionary rather than revolutionary means; but revolutions do not always introduce macro-change. They can fail, abort, halt, recede, fudge, muddle, diverge, transmute and/or provoke counter-revolutions. The complex failures and mutations of the communist revolutions, which were directly inspired in the twentieth century by the historical philosophy of Marx and Engels, make that point historically, as well as theoretically.

Yet no. Not only does fundamental change frequently develop via evolutionary rather than revolutionary means; but revolutions do not always introduce macro-change. They can fail, abort, halt, recede, fudge, muddle, diverge, transmute and/or provoke counter-revolutions. The complex failures and mutations of the communist revolutions, which were directly inspired in the twentieth century by the historical philosophy of Marx and Engels, make that point historically, as well as theoretically.

Lastly, for historians, it is also not surprising to find that gradual change is a powerful force in human history. There are many long-term trends that are slow and relatively imperceptible at the time. One example is the world-wide spread of literacy since circa 1700. Certainly there have been oscillations in the trend; but it is unlikely to be reversed, short of global catastrophe.

Lastly, for historians, it is also not surprising to find that gradual change is a powerful force in human history. There are many long-term trends that are slow and relatively imperceptible at the time. One example is the world-wide spread of literacy since circa 1700. Certainly there have been oscillations in the trend; but it is unlikely to be reversed, short of global catastrophe.